Facing worst shirt sales ever in the lead up to a World Cup, Brazil’s football federation the CBF has moved to ban sale of unofficial “Leftist” versions of the national team’s iconic jersey.

Despite clichés, the Brazilian national football team, or Selecão, is still along with Carnaval one of the enormous country’s unifying institutions, and part of its nation building project.

Though sometimes a platform for political protest, as it was in 2013/14, this was never related to what was happening on the pitch. So confident was the foreign media that 2014 World Cup would bring mass protests to the streets which could somehow topple the Rousseff government, that when they didn’t occur as expected, some outlets reported them anyway, sometimes using material from the year prior. Instead, idealistic young protesters who had been photographed in June 2013 with banners insisting that “We don’t want the World Cup we need schools and hospitals” were a year later posting selfies in the stadiums on instagram. The tournament was in Brazil and the majority were determined to enjoy it, regardless of political position – they’d already paid for it, after all.

But something has changed since 2014 in the relationship between Brazilians and the Selecão, and not because of the 7-1 rout against Germany, which may be quickly forgotten should Tite’s team perform to its potential in Russia.

Prior to the 2014 World Cup some conservatives were actually hoping for a humiliating Brazil defeat, believing that it could swing the coming election away from what was then a near certain victory for Dilma Rousseff. Rousseff went on to re-election anyway and the beginning of a breakdown in Brazil’s democratic order began immediately. With defeated Neoliberal Aécio Neves calling his supporters to the streets and vowing to obstruct any effort by Rousseff to govern, a synthesised movement began demanding her impeachment, a right-wing threat which had cast a shadow for some time.

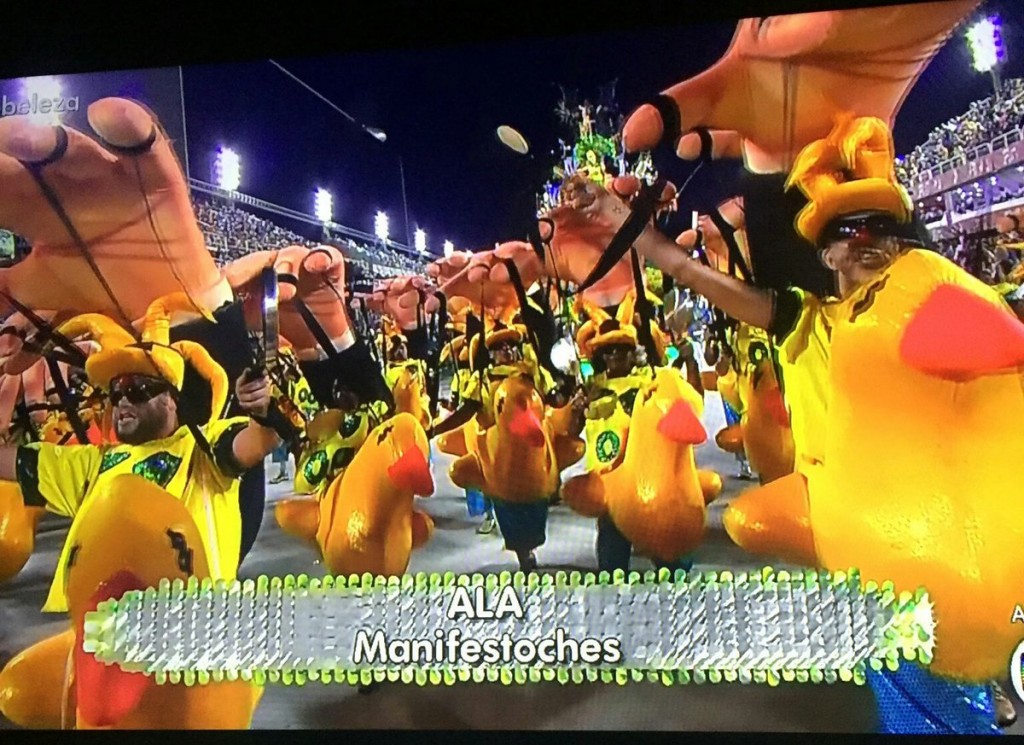

With overt promotion from oligarchic media network Globo, conservative newspapers such as Estadão, and protest groups connected to foreign hedge funds and the Koch Brothers libertarian Atlas network, a small kernel of cranks on São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista, screaming election fraud and for military intervention, grew to a few hundred thousand by March 2015, by then demanding Rousseff’s ouster by any means necessary. These protests, predominantly white and upper middle class, and ostensibly against a nebulous undefined “corruption”, had one other characteristic – a uniform of the yellow Selecão jersey. The aesthetic and manipulation of these demonstrations was parodied famously during Rio’s 2018 Carnaval Parade (pictured below).

The irony was not lost on Brazil’s left, the CBF being one of the most notoriously corrupt organisations in the country. As well as corruption, the CBF has all kinds of skeletons in its closet, and is filled with ex-Dictatorship personnel, some even directly implicated in assassination and torture. In addition, these 2015 demonstrations echoed the “Green & Yellow Nationalism” which brought to the streets an appearance of majority support for the Coup of 1964, and resulted in a 21 year dictatorship, and 25 years before Democracy was restored.

Emerging during the 1960s, “My only flag is the flag of Brazil”, or “My party is my country”, are still traditional conservative nationalist slogans, even when, like now, the underlying political agenda is erosion of the country’s sovereignty, but football, via Socrates’ Corinthian Democracy movement, played a crucial part in the campaign for the restoration of direct elections during the 1980s.

Forward to August 2016, with anti-coup protesters being beaten, tear gassed and shot with rubber bullets (to collective silence from the english language media), some pundits laughably suggested that Brazil’s victory in the Rio Olympic football tournament would be the catharsis that the country needed to “move on” from a coup d’etat that was not only being denied, but still unfolding, with Dilma Rousseff awaiting her final removal from the presidency. This episode is recorded in the award-winning new documentary ‘O Processo (The Trial)’ by Maria Augusta Ramos.

The notion that football would bring closure was as familiar as it was unwelcome. In 1970, Dictator Emiliano Medici, responsible for torture, assassination and brutal repression, used the victory in Mexico as propaganda during what is considered the darkest period of the dictatorship. “Brazil: love it or leave it”, was the regime’s slogan of the era, with many forced to do the latter.

2006 film ‘The year my Parents went on vacation’ dramatises this period of disappearances and exile. It has a memorable scene where opponents of the Dictatorship, young middle class Socialists, watch Brazil’s opening game against Czechoslovakia. Declaring that a victory for the Czechs would be a victory for Socialism, the group mutedly celebrate when the eastern european team score first, only to collectively lose it when Brazil equalise. You can be confident that football will usually, temporarily succeed in overriding political sentiment in any nation which enjoys it, not least in Brazil. That’s one cliché that rings true at least.

But in 2018 the traditional yellow Selecão jersey is now politically toxic, having been transformed into an ultraconservative symbol that few on the left would be comfortable wearing. It is also prohibitively expensive for average Brazilians. As a result a mini industry has developed around the trend for alternative attire with which to show support for the Selecão but in doing so oppose the Coup, the extreme austerity (which has hit the working class hardest) / anti-national policies of hated President Michel Temer, and the corrupt CBF itself. Beyond that some are so disillusioned with post-coup Brazil that they don’t care about the team at all anymore.

Elections are scheduled for October, but with serious doubts that they will take place in a free and fair manner. Leading candidate, former president Lula, who is polling over double his nearest competitor (fascist Jair Bolsonaro), is now jailed for 12 years in what many consider a politically motivated conviction to prevent his return to the presidency. On charges for which there was no material evidence provided, in a prosecution conducted in illegal, informal collaboration with the US Department of Justice, Lula was denied habeus corpus in a vote of 6 to 5 by the Supreme Court following a televised threat from the head of Brazil’s armed forces of consequences should Lula be released. Many conservative politicians, with ample evidence against them, currently walk free, with their cases shelved or abandoned altogether. Both Lula and his Workers Party insist he will run from prison if not released prior to the election.

Now synonymous with the fight for a return to democracy, small protests are expected at the World Cup in Russia demanding Lula’s release from jail, as occurred at Brazil’s friendly versus Croatia on June 3, at which personnel from TV Globo tried and failed to expel demonstrators, then edited their flags and messages out of the broadcast.

[qpp]