Brazilians do not scare easily, but a media narrative saying so paves the way for northern acceptance of a return to fascism.

by Brian Mier

In the seminal book, Manufacturing Consent, Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman depict the commercial media as “powerful ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function, by reliance on market forces, internalized assumptions, and self censorship, and without overt coercion”. In Brazil, we witnessed the propaganda function in 2014, when, during an election year, the northern media transformed its image of the nation from winner country to failed state. A key example was Simon Romero’s New York Times piece From Boom to Rust which was accompanied by a dozen black and white photos of sad looking people in front of unfinished construction projects, most of which were eventually completed. Once in place, this narrative shifted to the subsequently debunked story, repeated ad nauseam, that Dilma Rousseff and Lula received millions of dollars in bribes from the Petrobras Petroleum corporation. Then there was the 2016 narrative that Dilma Rousseff’s illegal impeachment was not a coup, especially disappointing to hear from so-called progressive publications like the New York Times and Guardian, since progressive Brazilians unanimously believe that it was.

After truckers and petroleum workers anti-privatization strikes ground the nation to a halt last week, an article sprung up on the social media, shared by some people who should know better, in which corporate pitch man Brian Winter compares the strikes to a zombie apocalypse and justifies the fact that many (but not most) Brazilians are clamoring for a return to military rule because they are “scared”. The cognitive effect of associating the strike with a zombie apocalypse is that readers think things are so terrifying that a military takeover could be Brazil’s only salvation. As in the case of so many articles about Brazil that initially appear in the corporate advocacy group AS/COA’s publication Americas Quarterly, the narrative is already disseminating into commercial newspapers. In the Guardian, Dom Phillips says, “Brazilians were spooked by the 10 day protest.” Ironically, further down in the article, he acknowledges the fact that 87% of Brazilians supported the strike. Are Brazilians spooked of the strike or did they support it?

One thing I have learned in my quarter century living in this wonderful country is that Brazilians do not scare easily. They definitely do not scare as easily as American or English people. To give a quick anecdotal example, Brazil was more dangerous in the 1990s than it is today. I lived in a favela for 6 years and have been in gunfire situations many times in various cities in Brazil. I can recall, on more than one occasion, being laughed at by Brazilians for ducking to the pavement or fleeing when people around me started shooting at each other.

Brazilians certainly do not scare easily and yes, 87% supported the “spooky” truckers’ strike, but a sizable minority of Brazilians do have fascist sympathies. I’ve known Brazilians who support a return to military rule since 1991. Frankly, there has always been a part of the population who like the idea of dictatorship. After all, we are talking about a country in which a large percentage of the white middle class supported the death squad assassinations of homeless children during the 1990s, where enthusiastic moviegoers stood up and cheered during torture and execution scenes of Afro-Brazilian teenagers in the movie Elite Squad in 2007, and where black people were forced to ride in service elevators until well into the 21st Century.

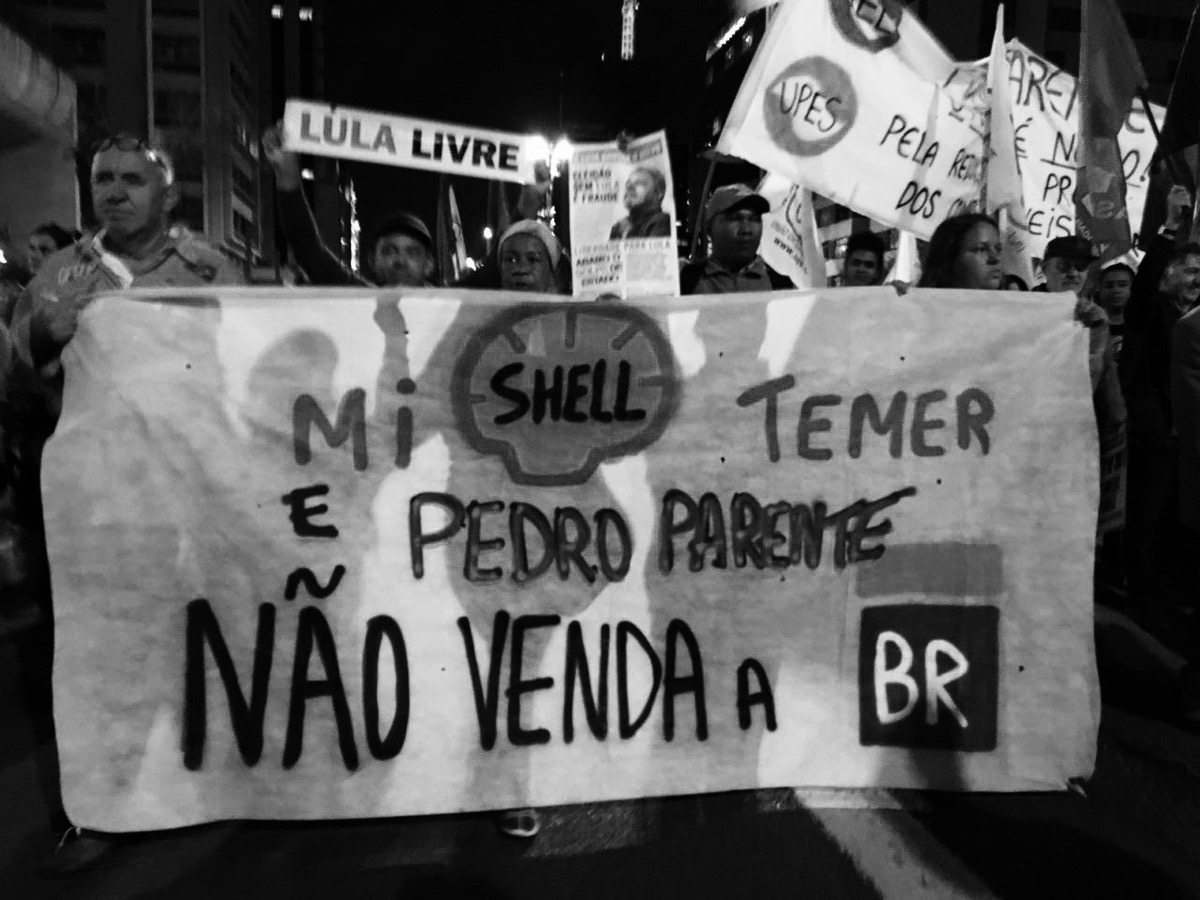

So why, in the aftermath of a historic truckers’ strike which paralyzed the nation, and a national petroleum workers strike (ignored in the media) which forced the resignation of Petrobras President Pedro Parente, would a new narrative develop about how scared Brazilians are clamoring for dictatorship? I suggest the following as a possible cause. Since the 2016 coup, American and European petroleum companies like Shell, Chevron and BP have made billions of dollars buying Brazilian offshore drilling rights at vastly below market rates. The Temer government also gave them tax exemptions that, over the course of the next 20 years, will save them an estimated $280 billion. Petrobras’ neoliberal restructuring, abandoning charging the actual cost for fuel produced in Brazil and linking to the international barrel price has driven prices up by over 50%, forced 1.2 million families to abandon cooking gas for scrap wood, and is strangling the working and middle classes that roughly correspond to the 87% of the population that supported the strike. The Petroleum unions and a large percentage of the truckers are demanding a reversal of Petrobras’ pricing policy and a reversal of the last 2 years of privatizations. They put the government on the ropes last week and it has already given into some of their demands, firing Pedro Parente and a career Shell Oil executive who was inexplicably placed on the Petrobras board of directors last year. Neither the truckers, the petroleum workers unions, nor other unions across the country who struck in solidarity with them last week say they will ease up until the pricing policy and privatization are reversed. If this happens, companies like Chevron, Exxon and Shell, which purchased content in the Guardian in 2016, will lose hundreds of billions of dollars. Depending on how the political conjecture plays out over the next few months, the only way to prevent this from happening and protect foreign oil interests may be a roll out of military control of the security apparatus from Rio de Janeiro to the entire nation, or even a military takeover. One way to get a northern public comfortable with the idea of a return to neofascist military rule is to paint a human face on it. It’s not that they are fascists, Phillips and Winter imply, they are just scared.

[qpp]