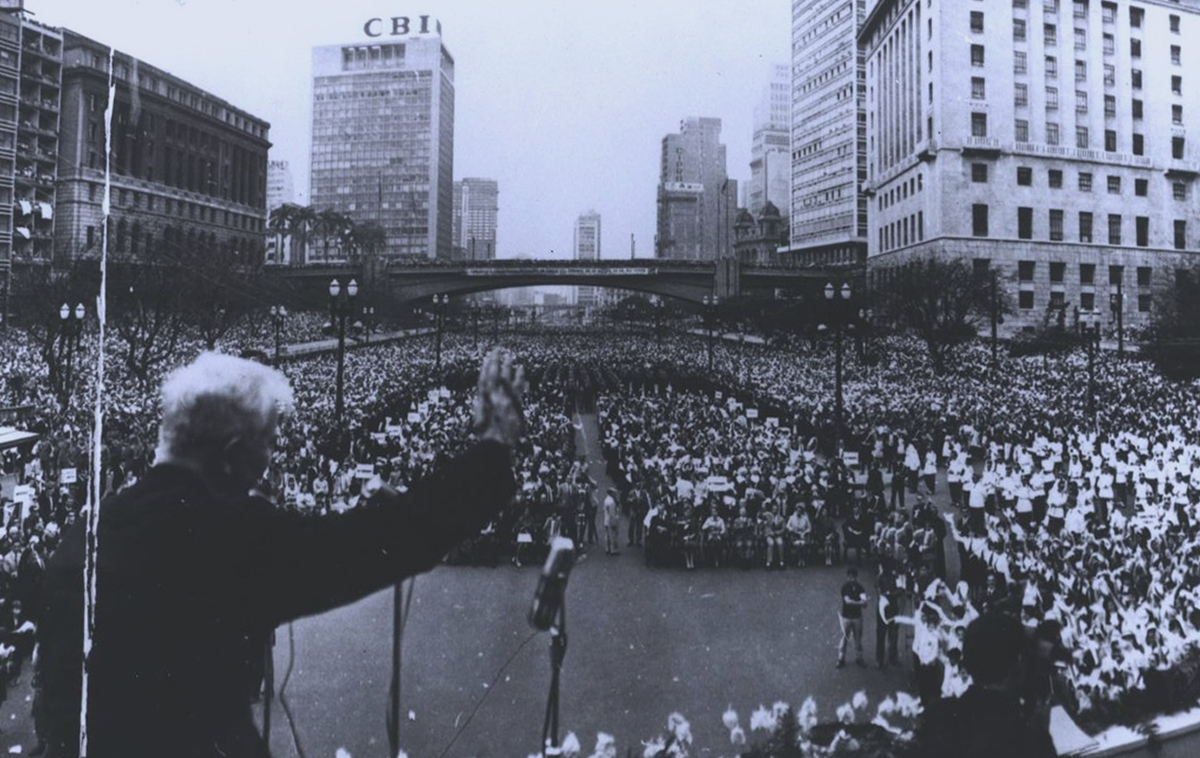

Successive demonstrations in its most important cities, brawls between militants of opposing ideological sides who see the other as an enemy rather than a political adversary, growing numbers of strikes, verbal and written attacks in the media, rising polarization in Congress. A good description of what has been taken place in the country of the future in the last several weeks, this narrative would be similarly accurate in describing events leading to as well as immediately after the military coup of 1964. Indeed, in the first years of the decade and even towards its end, when the authoritarian regime tightened its grip and curtailed most forms of political life, Brazil was immersed in intense activism reflecting, at the same time, the vibrancy of its flourishing democratic institutions, rising civil society, and protracted but continuous path of socio-economic and political inclusion, as well as a reasserted resistance against substantive social transformations from different sectors of its entrenched, and mostly conservative ruling elites.

Though history doesn’t seem to repeat itself in the same ways, it is clear that deep-seated structural factors tend to encroach upon one’s reality unless they have been sufficiently weakened. In fact, the recent, rapid though not necessarily sustained, rise of traditionally excluded groups to the economic and political lives of the country notwithstanding, Brazil’ political landscape since last year’s presidential election resembles more that of a country mired in Cold War rhetoric rather than that of a nation in the path of consolidating its transition from autocratic rule to fully democratic life. In what has been called by some the ‘third round’ of the recent electoral proceedings, the fact is that many who supported the opposition candidate, senator Aécio Neves, in his unsuccessful bid to the presidential seat last October, have refused to accept the outcome of the election and have since then taken to the streets to demand Dilma Rousseff’s, the narrowly reelected president, ousting from power – if needed by means of a military coup. Further complicating the prospects of dialogue between the opposing sides, the current composition of Brazil’s parliament is one that reflects its ideologically most conservative alignment in over 60 years, and, to her supporters greatest dismay, the recently appointed new finance minister of Rousseff’s second term in office is pushing for a sharp cut in public investment and social expenditures in order to bring down the country’s rising inflation, thus appeasing domestic and international investor as well as global financial rating agencies.

Similarly to what has happened in the country in the last decade, in the 1950s Brazil witnessed accelerated rates of growth amidst rising mobilization of multiple sectors of its increasingly active civil society. Also in tandem with these latest events, and despite being very transformative in many ways, mid-century economic achievements were not equally distributed across the Brazilian society and powerful ruling groups continued to be able (then and now) to unevenly influence the course of political developments. Equally relevant, and also finding resonance with what has been seen in the last couple of years in the country, most gains attained by lower socio-economic segments during the industrialization of the postwar developmentalist experience were rapidly depleted by the rising costs of living and the diminishing quality of social services mired by lacking investments amidst growing demands from recently arrived members of the national economy.

By the same token, resembling to some extent the optimism shared by middle-class sectors under the so-called golden years of the Kubitschek’s administration (1956-1961), during the final phase of the Lula’s administration (2003-2010), Brazil saw an accelerated pace of economic growth, largely derivative of the country’s emergent domestic market and its reasserted insertion in the global economy. Also in tandem with the focus placed on basic literacy programs headed by the worldly acclaimed educator Paulo Freire in the early 1960s, Brazilians witnessed new professional opportunities created by the expansion of access to vocational and academic institutions in recent years. Similarly echoing earlier historical dynamics, but in a more tragic fashion, both approaches to long-term transformations in the deeply seated hierarchical structures of the Brazilian society have, soon after their implementation, been targeted many times in the media as excessive, unnecessary, or even dangerous. In fact, one of the more eloquent aspects of these parallel historical trajectories relates to the fact that, in the past as well as today, the modest materials improvements seen in poor people’s lives – their precarious and structurally very limited inclusion into the ranks of the broader Brazilian society notwithstanding – has mostly been seen as either too costly or politically menacing to the traditional, said-to-be socially well-balanced and racially democratic society.

Either sixty years ago or simply today, the many changes undergone in the country during this period notwithstanding, the fact remains that socially oriented public policies, even if aimed at only marginally reconfiguring the broad contours of the national society, continue to be deeply opposed by powerful social segments. No one should minimize the gravity of the recent moves towards restrictive social legislation and the growing calls for rolling back social programs responsible for the country’s most significant figures of economic amelioration in history. But even if we may still need to learn more from the lessons of the past insofar as building a more inclusive society, the positive note is that Brazil has now a much more empowered and mobilized civil society which, so far, has been able to resist more authoritarian courses of action. One hopes this may indeed prove to be a key difference between the country’s recent past and the present-day.