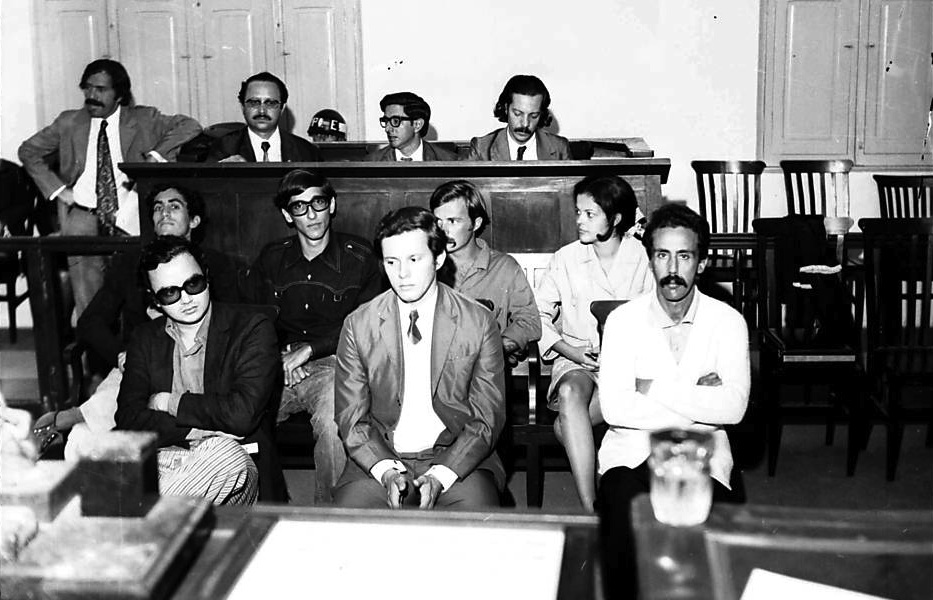

Dilma Rousseff is often regarded as a great unknown outside of Brasil but she has been an active force in official politics since the mid 1970s when she attended meetings organised by the only opposition party allowed by the then Military Dictatorship, the Democratic Movement Party (MDB), while studying Economics at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Rousseff had come of political age during the early years of the Ditadura following the coup in 1964 and went on to join an armed resistance group, then was a founder of the Revolutionary Armed Vanguard Palmares (VAR Palmares). Rousseff was arrested for subversion in 1970 and spent three years in prison. Rousseff rarely speaks of this time but the torture she suffered was brutal. Subject to suspension from a rod by the hands and feet called ”Pau de Arara” in Portuguese and at two points beaten so badly her jaw was dislocated and her uterus ruptured. To her credit, even to her detriment, Rousseff has not used this to garner sympathy from the electorate.

Rousseff’s initial party political activity was with leading politician Leonel Brizola’s fledgling Democratic Labour Party in the 1980s. From that point on Rousseff followed the path of a career adviser and bureaucrat in Rio Grande do Sul. She first rose to prominence in 1999 when she warned then President Fernando Henrique Cardoso of an impending energy crisis. Her early action was widely credited as averting emergency in Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná and Santa Catarina.

During this period Rousseff switched to the Workers’ Party – Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT – under future president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Once in office Lula appointed Rousseff Minister of Energy where she first worked with then Environment Minister, now political rival Marina Silva. Rousseff and Silva immediately clashed, to the point were group meetings were required between the ministries to mediate the conflict. Politics in Brasil are much like everywhere in that negotiation and comprise are often at the heart of stable government, however Silva’s intractability and Rousseff’s pragmatism created bad blood that is very evident in the current campaign. Rousseff rarely acknowledges Silva other than in strong attack adverts – a new phenomenon this election – and for Silva’s part she mostly concerns herself with criticism from Lula and seems unwilling or unable to address Rousseff directly.

In 2005 it became clear that a corruption scandal that started in the state of Minas Gerais with Cardoso’s PSDB had seeped its way into the Worker’s Party coalition. It was revealed that members of the Progressive Party (PP) and Brazilian Democratic Movement Party among others had solicited bribes for votes from Workers’ Party senior officials on number of key tax and social security reforms that had been stuck in legislative limbo for years. The then Chief of Staff José Dirceu – pegged as Lula’s successor – was implicated and resigned. Rousseff was chosen as Dirceu’s successor in a rare moment of meritocracy in Brasil’s deeply clientelist party political system.

In 2010 Rousseff launched a bid to succeed Lula against former São Paulo State Governor & city major José Serra. Serra had been riding high in the polls for some time and was widely expected to win the election. Once the campaign began in anger Serra’s campaign weakened and he made a number of strategic errors, including an insincere bid for the evangelical vote by creating a phantom controversy over abortion. Something common in American politics but badly backfired in Brasil. It is doubtful that without Lula’s backing and active support before and during the campaign that Rousseff could have been chosen to run or elected. Backroom politics in Brasil are a dirty business and without Lula knocking heads together and making deals in the background the coalition could easily stagnate and collapse. But Rousseff quickly showed herself not to be a mere puppet firing a string of Lula appointees within months of office for accused wrong doing, showing little of the usual deference to coalition partners.

Rousseff’s first term started as a clear continuation of the second Lula mandate. Public service programs were expanded and Brasil has continued much on the same path as it had for the previous Workers’ Party administrations. However Rousseff’s big idea at the beginning of her first term was to use the slowing economy to ease down Brasil’s very high interest rates. This did not have the desired effect and historically low inflation began creeping to upper Central Bank tolerance levels. The externalities from this have overshadowed much of Rousseff’s term.

Despite accusations of being a Statist, Rousseff’s history does not indicate this; she expanded private investment in the energy sector and the public-private infrastructure concession system has been ramped up. The main exception has been using state energy company Petrobras to control inflationary pressure via selling imported refined petroleum at a loss. But this has been a short-term policy to offset inflation, not as the rule. The huge weighting that Petrobras has on the Brazilian stock market creates a false assumption that Rousseff’s ratings effect the company’s share prices, however the reality is this is mostly coincidence not causation as the real reason for Petrobras’ stocks price rising is record production levels and the discovery of new large confirmed deposits over the past year.

Overall Rousseff’s mandate goals remain as they did in the two previous administrations. With the Lula period widely regarded as the most successful in modern history rocking the boat of Brasil’s unwieldy coalition system has not been a priority. It is important to realise that the interests of foreign press and the internal priorities of the Brazilian state are not always the same. Much of the criticism focused on Rousseff’s administration relates to Brasil’s macro economic policies which still recognise the need to protect local industry against external competitive advantage and use industrial policy as social policy acknowledging that formal employment trumps abstract adherence to prevailing classical economy theory.

Rousseff’s calculated risk in pushing down interest rates did not work, whether this is a firing offence in the eyes of Brazilian voters will be revealed in the coming weeks.

[qpp]