Rio de Janeiro hasn’t elected a progressive mayor since the 1980s but this year progressives are celebrating anyway, as center right candidate and former Mayor Eduardo Paes beat a man widely considered the worst mayor in Rio de Janeiro’s 455 year history.

By Luiz Matheus*

The left’s failure to mount a coalition ticket, with vote divided evenly between Benedita da Silva (PT) and center left candidate from Martha Rocha (PDT), is one of the factors that led to a second round run off between former mayor Eduardo Paes (2009-2016) and far right incumbent Marcelo Crivella, who was supported by President Jair Bolsonaro.

With a record abstention level of 34.45%, progressive voters opted for the lesser evil option to prevent the reelection of christian fundamentalist mayor Marcelo Crivella, who had a 72% disapproval rating. The fear of having an incompetent and intolerant mayor for another four years had progressives lining up behind the right wing coalition supporting Eduardo Paes, in a kind of “broad front” that was both undesirable and embarrassing.

Eduardo Paes was elected Mayor of Rio for the 3rd time but now faces a complicated scenario. He will take over a city government from Crivella that has a deficit of over R$10 billion, thousands of city workers who are owed months of back pay, and hospitals on the brink of collapse from the Covid-19 pandemic. How did Rio de Janeiro, the “Marvelous City”, the postcard of Brazil, arrive in this chaotic situation which led to the population having to choose between a bad candidate and one who was even worse?

Who is Eduardo Paes?

The fiscal and public health crises that Eduardo Paes will have to deal with upon taking office in January are unprecedented challenges which he never had to deal with during his previous 2 terms in office. His 8 years as Rio Mayor were marked by restructuring of the municipal debt and record levels of tax revenue. During his government the investment budget rose tenfold, from R$400 million to R$4 billion. Rio de Janeiro also became the only Brazilian city to receive an investment rating from Standard and Poor.

The city hosted mega-events such as the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), World Youth Day and the 2014 World Cup. However, none of those events can compare with the 2016 Olympics, which represented an opportunity for unprecedented urban transformation. During Paes government Rio de Janeiro transformed, in the eyes of its critics, into a city of spectacle, governed by businessmen.

While undergoing a redesign for the Olympics and Paralympics, Rio’s citizens began to feel the deepening effects of an urban development model that prioritized big business and real estate speculation. On the one hand, Paes resurfaced roads, opened a Bus Rapid Transit System (BRT), inaugurated anti-flooding drainage systems and carried out the gigantic task of revitalizing the entire Port Zone in what, at the time, was the largest public-private partnership in Brazil. In addition, he inaugurated the Olympic Park, where the arenas for the Olympics and Paralympics were erected.

2012 anti-eviction protest in Vila Autodromo favela, which was later razed by the Paes administration for the Olympics (foto Brian Mier)

On the other hand, the Paes government conducted forced evictions of families living in favelas, privatized management of the municipal public health system, and used the municipal guard to repress street vendors through an operation called, “shock of order.” Resorting to the old political strategy of cronyism his 2008 electoral victors was won, essentially, through the votes of people living in neighborhoods dominated by paramilitary militias. As mayor, his governing coalition included city councilors connected to the militias.

Charisma: while waging war against the city’s street venders, Mayor Paes held a press confernence/photo op to publically declare the city’s beloved beachcombing iced tea peddlers as “cultural heritage of Rio de Janeiro.”

However, these contradictions did not initially affect his popularity. At the time, Paes belonged to the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB) – the political party of then vice-president Michel Temer and an important ally of the Lula and Rousseff governments at a time when the federal government was praising the union between national and local governments in its official advertisements. Presidents Lula and Rousseff (Workers Party/PT), Mayor Eduardo Paes and state governor Sérgio Cabral (PMDB) entered in a political partnership that symbolized the integration of the three spheres of public administration – Federal Government, State Government and City Government – which solidified the PT-PMDB coalition at the national level. Thus, in Rio, PT and PMDB were united in a political partnership synthesized in the governmental slogan “joining forces”. This alliance broke up during the lead up to the 2016 coup, during which members of Congress from Rio who were affiliated with Paes voted in favor of the illegal impeachment of president Dilma Rousseff.

Crivella abandons the city

The end of Eduardo Paes term in 2016 represented a quick and pronounced change for Cariocas, because incoming mayor Marcelo Crivella had a different profile and style from Paes. Crivella is a licensed bishop in the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), one of the most influential neo-Pentecostal churches in the world. He was elected Senator in 2002 and reelected in 2010 with strong support from the fundamentalist christian electorate, and arrived at City Hall in 2016 surfing the conservative, anti-political wave that swept over the nation after 5 years of relentless media and lawfare attacks against the Brazilian left.

Crivella took office in January 2017 promising to cut spending and “manage tax revenue with more austerity”. He cut R$3.2 billion from the budget in his first 2 months in office alone, and this had a negative effect on city services. During his first 2 years in office there was a 73% cut in road maintenance. A Rio de Janeiro mayor had never invested so little in flood prevention. The public works completed for the Olympics were abandoned. Lack of funding for the public health system led to a collapse of municipal public hospitals due to lack of beds, doctors, medicine and medical equipment.

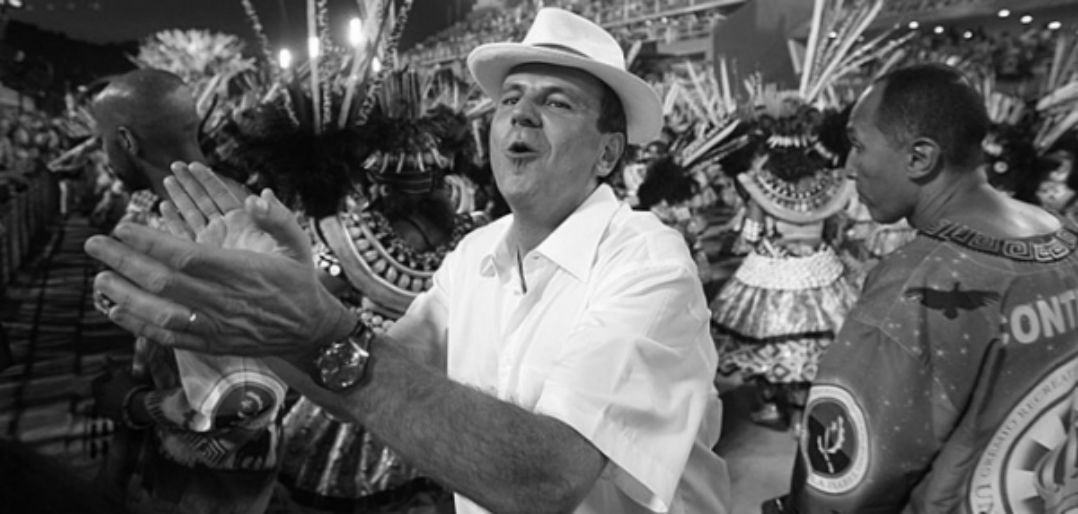

Delays in public works and the mayor’s inertia became the target of jokes among the local population. “Where is the mayor?” and “Does the mayor live in Rio?” became common refrains. Cariocas began to joke about missing Paes. The general feeling was that Crivella was incompetent, absent and lousy at the job he was elected for. Paes, in contrast, had charisma and liked to brag about how being mayor of Rio was the “best job in the World”. As mayor, he was present in all of the big events, whether wearing a traditional white pork pie hat during carnaval or putting on a raincoat and going out on the streets to monitor flooding.

The contrast between the personalities became even greater when Crivella began to mix politics with religion. He nominated evangelical christian preachers as regional superintendents, and was almost impeached after offering space in public buildings for evangelical churches and helping members of his church cut the line on the waiting list for surgeries in the public hospital system. He demonstrated his religious fanaticism when he vetoed a cultural exposition alleging that the art “disrespected religious symbols”. He tried to censor a book exhibited in the Rio de Janeiro Literary Biennial which had a picture of a gay kiss in it, and he slashed funding for carnaval, which is considered to be diabolical and sinful by evangelical christian groups.

In one recent scandal it was revealed that city workers called “Crivella’s guardians” were stationed in front of public hospitals specifically to cause problems for journalists reporting on the health system, under specific orders from the Mayor. This censorship was taking place in the middle of the Covid 19 pandemic, during a period in which ICU units were overflowing and 16,000 public health workers had worked for months with no pay. As of December, 2020, Rio de Janeiro city has had over 150,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 13,000 deaths, with a mortality rate per 100,000 residents that is 66% higher than the city of São Paulo.

Rio’s left

Crivella bet on being reelected through a strong alliance with Jair Bolsonaro. This in exchange for his support during the 2018 presidential elections, when he set up a local electoral machine for Bolsonaro that did not only rely on the evangelical churches to get out the the vote, but had the alleged involvement of the militias (like Paes in 2008). The map of voting in the first round of the 2020 mayoral elections shows that one of the few districts of Rio that Crivella won was the suburban neighborhood of Campo Grande, which is controlled by Rio’s largest militia, the League of Justice.

Neither Bolsonaro’s support, nor the supposed coalition between the churches and the paramilitary militias was enough to revert the extremely high rejection rate of his government. The only demographic group that continued to support him was the evangelical Christians, and he bet on their support in the second round. However, he may not have even made it that far if it weren’t for the failure of the three largest parties on the left to form a coalition. Instead they fielded 3 candidates in the first round: Benedita da Silva (PT), Martha Rocha (PDT) and Renata Souza (PSOL).

One of the biggest hopes on Rio’s left was PSOL Congressman Marcelo Freixo, who ran for mayor in 2012 and 2016, when he lost to Crivella in the second round. In 2020, he conditioned his candidacy on an alliance of the left. Party leaders negotiated, but the idea was killed by Ciro Gomes’ PDT party, which only agreed to enter the coalition if its candidate, state congresswoman Martha Rocha, ran as the mayoral candidate. Even though he was polling in second, Freixo decided not to run.

Freixo and his party were turned into a campaign issue during the second round. Upon realizing that his chances for reelection were slim, Crivella began a defamation campaign which drew on elements of the QAnon conspiracy theory. He recorded a video accusing Paes of making a deal with PSOL so that it could nominate an Education Minister who would “promote pedophilia in the public school system”. His campaign also distributed pamphlets connecting Paes to Freixo, that said both were in favor of “legalizing drugs” and distributing a “gay kit” to children. For this slander, both Paes and PSOL pressed charges against Crivella and the state electoral court accused Crivella of defamation and false propaganda.

In response to Crivella’s campaign the PSOL announced that, despite its support of a “lesser evils” vote for Paes, it would remain in opposition in city council as it did During Paes’ previous two terms (2009-2016), during which the PT and PDT joined the governing coalition. This time around, as Paes has switched parties to the farther right DEM (which is the legacy party of dictatorship era ARENA) it is important for the progressive camp in Rio de Janeiro to remain in the opposition. The goal of defeating Crivella was successful and although it was unable to unite behind a single candidate, it looks like this time, Rio’s the three largest left parties will unite in opposition to the Paes administration.

* Luiz Matheus is the psuedonym used by a professional journalist from Rio de Janeiro, who out of fear of repercussion asked us not to use his real name on the byline of this article, which was written exclusively for Brasil Wire.

[qpp]