Brasil Wire Exclusive: Britain secretly lobbied far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro on behalf of its pharmaceutical, oil and mining interests in lead-up to the 2018 election. The companies include AstraZeneca, whose Oxford Covid-19 vaccine remains the only one bought by the Brazilian federal government, despite being unready for production.

By John McEvoy, Nathalia Urban | Português

A secret document obtained by Brasil Wire reveals that the British government lobbied neo-fascist candidate Jair Bolsonaro on behalf of British pharmaceutical, oil and mining companies in the run-up to the 2018 presidential election.

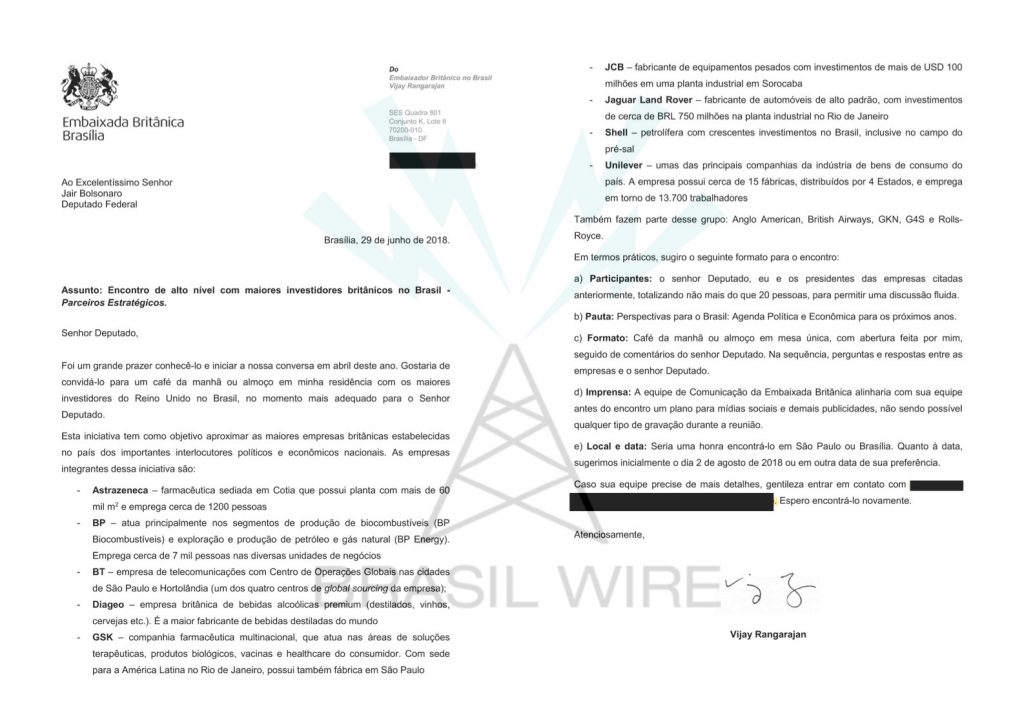

In a private letter personally addressed to Bolsonaro on 29 June 2018, then-British ambassador to Brazil Vijay Rangarajan invites the presidential candidate to his own residence to meet a number of “Strategic Partners” in Brazil. Those partners included pharma multinational AstraZeneca, as well as extractive giants BP, Shell, and Anglo American.

Publication of this letter comes at a crucial time. Bolsonaro has placed almost all hope for Brazil’s Covid-19 response into the Oxford/Astrazeneca vaccine while refusing to place orders for alternatives. After almost 200,000 Brazilians have died from the virus, the second highest number globally, his apparent personal investment in Oxford/AstraZeneca has been described as “homicidally negligent” and “absurd”.

Bolsonaro’s reliance on the AstraZeneca vaccine raises a serious question: did British lobbying efforts lead to a sweetheart deal with the company?

Strategic Partners

In March 2020, Brasil Wire revealed basic details of previously undisclosed meetings and correspondence between senior British officials and Jair Bolsonaro before, during, and after the Brazilian 2018 election campaign. These meetings raised concerns given Bolsonaro’s overt declarations in favour of dictatorship, torture, and violence against Indigenous communities in Brazil.

The first meeting between both parties was on 10 April 2018, six months before the election, and was attended by Bolsonaro, Rangarajan, and redacted names. Yet on 9 April 2018, then-Chief Secretary to the Treasury Liz Truss set off for Brazil on an official visit to discuss “free trade, free markets and post-Brexit opportunities”.

The Treasury has stonewalled a Freedom of Information request about Truss’ activities in Brazil, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) has refused to release any additional information regarding its meetings with Bolsonaro. The FCO took a full eight months to comply with the initial FOI request.

However, Brasil Wire can now reveal a key motivation behind Bolsonaro’s meetings with British officials in the lead-up to the 2018 election.

On 29 June 2018, Rangarajan followed up on his April meeting with a private letter to Bolsonaro regarding Britain’s “Strategic Partners” in Brazil. “Deputy Bolsonaro”, the letter reads, “it was a great pleasure to meet you and initiate our conversation in April of this year. I would like to invite you for a morning coffee or lunch in my residency with the largest British investors in Brazil, at a time that best suits you”.

The first on the list of British investors is pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca. Other investors include oil and mining giants BP, Shell, and Anglo American; arms and security companies Rolls-Royce and G4S; as well as British Airways and vehicle manufacturers Jaguar Land Rover.

Invitees to the meeting include Bolsonaro, Rangarajan, and senior representatives of the Strategic Partners – “in total no more than 20 people, to allow for a fluid discussion”. Rangarajan concluded the letter telling Bolsonaro: “I hope to meet you again”.

In November 2018, Bolsonaro and Rangarajan met once again, alongside two of Bolsonaro’s sons, vice-president Hamilton Mourao, General Augusto Heleno, unnamed “others”, and redacted names. The FCO has also refused to provide any details about this meeting.

Britain was thus lobbying a neo-fascist candidate on behalf of British big pharmaceutical and extractive companies in the run-up to Brazil’s most controversial election since the end of Brazil’s dictatorship (1964-1985). Indeed, the election was the culmination of a slow coup, following the spurious impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and the imprisonment of presidential frontrunner Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in April 2018.

Brasil Wire has also obtained private emails between Rangarajan and Brazilian officials in the years leading up to the 2018 election. An email sent in April 2017, subject header “Briefing [redacted] Shell”, notes that “the Strategic Partners, led by Vijay, met presidential candidate [redacted] in Sao Paulo on 22 June” (2016).

Though Bolsonaro had not yet formally announced his candidacy in June 2016, Brasil Wire has first-hand knowledge that the British mission under Rangarajan’s predecessor, UK Ambassador Alex Ellis, was in communication with him from as early as 2014. It could not be confirmed whether the redacted name in the 2017 email is Jair Bolsonaro, or another presidential candidate.

June 2018 Letter from the UK Ambassador to then Presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro

British Interests

These lobbying efforts fall in line with an earlier British pressure campaign. In November 2017, Minister of State for International Trade Greg Hands lobbied Brazilian Minister of Mines and Energy Paulo Pedrosa to “weaken tax and environmental laws and local hiring policies” to advance the interests of British mining companies.

Bolsonaro has also proven a lucrative president for many of the British companies listed in Rangarajan’s invite. British mining giant Anglo American has made over 300 research applications to explore 18 indigenous territories in the Amazon, some of which are home to uncontacted peoples. This is just one episode in a transnational scramble to exploit the region since Bolsonaro came to power.

By 2018, Shell and BP — with whom the UK ambassador to Brazil met over twenty times since 2017 — had already accumulated 13.5 billion barrels of Brazil’s oil, more than the country’s own company Petrobras, and for only a fraction of the cost.

AstraZeneca and Bolsonaro’s “homicidally negligent” Coronavirus response

Brazil has suffered the world’s second-worst number of Covid-19 death rates.

Bolsonaro has been criticised in Brazil and internationally for relying on the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine which, unlike other operations, is not yet ready for production. On 3 December 2020, the federal government purchased 100 million doses of AstraZeneca vaccine for R$1.9bn (US$360mn).

Meanwhile, the Bolsonaro government continuously refused to sign contracts with Pfizer or Chinese SinoVac – both of which are producing the vaccine already. SinoVac even has a product developed and tested in collaboration with São Paulo’s renowned Butantan Institute, yet this promising avenue has been consistently eschewed by the president.

On 16 December, on orders from Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court, the Bolsonaro government finally presented its vaccination strategy. At a press conference, he confirmed that Brazil would buy any vaccine passed by the Anvisa regulatory body for US$3.93bn. Many are concerned, however, that Bolsonaro will continue to use his leverage within Anvisa to block the vaccines he doesn’t approve.

Given Brazil’s lack of preparation linked to near-total reliance on AstraZeneca, Bolsonaro’s Covid-19 response has been described as “homicidal negligence”, “criminal recklessness”, and “absurd”.

Though the AstraZeneca model is currently not-for-profit, a memorandum of understanding between the company and a Brazilian manufacturer has shown that AstraZeneca could begin making profit on the vaccine as early as July 2021.

Bolsonaro’s apparent total reliance on the AstraZeneca vaccine raises serious questions about his relationship with the British government and the company itself. Did British pressure, suspicion of China, or criminal negligence lead Bolsonaro to this situation?

[qpp]