In the first part of this series on British involvement in Brazilian internal affairs it was revealed that the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office has deleted its record of correspondence and meetings about Brazilian elections with strategic communications companies SCL and Cambridge Analytica. In this second article, more freedom of information requests show previously undisclosed meetings between representatives of the UK Government, Jair Bolsonaro, his family, and his allies, months before the far-right candidate’s controversial victory at the 2018 election. Part three to follow shortly.

By John McEvoy, Nathália Urban.

A number of Freedom of Information requests have revealed basic details of previously undisclosed meetings and correspondence between British officials and Jair Bolsonaro before, during and after the Brazilian 2018 election campaign, including when current UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson was Foreign Secretary. The meetings suggest a continuing trend of British support for far-right movements and governments across Latin America.

The authors have firsthand information that Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) personnel had some level of contact with Bolsonaro as early as 2014, and there can be no doubt that by April 2018 the UK government knew about his extreme views and horrific public statements.

In 1993, Bolsonaro claimed he was “in favour of a dictatorship” in Brazil; in 1999, he said he was also “in favour of torture” and that 30,000 people needed to be killed for Brazil to function; in 2002, he told a reporter “if I see two men kissing in the street, I’ll hit them”; in 2010, he said he would be “incapable of loving a homosexual child”; in 2012, he praised Adolf Hitler as “a great strategist”; in 2017, he claimed he would “give carte blanche for the [Brazilian] police to kill” and stated that ”where there is indigenous land, there are riches beneath”; in 2018, he vowed that “these red lowlifes [the Left] will be banished from our homeland”.

In light of this reputation, one of the editors personally advised former British ambassador to Brazil, Alex Ellis, against meeting Jair Bolsonaro in 2014.

Today, Bolsonaro is deeply unpopular, facing protests at home and a new global outcry over his reaction to the Coronavirus pandemic, while his increasingly erratic behaviour threatens the safety of the Brazilian population.

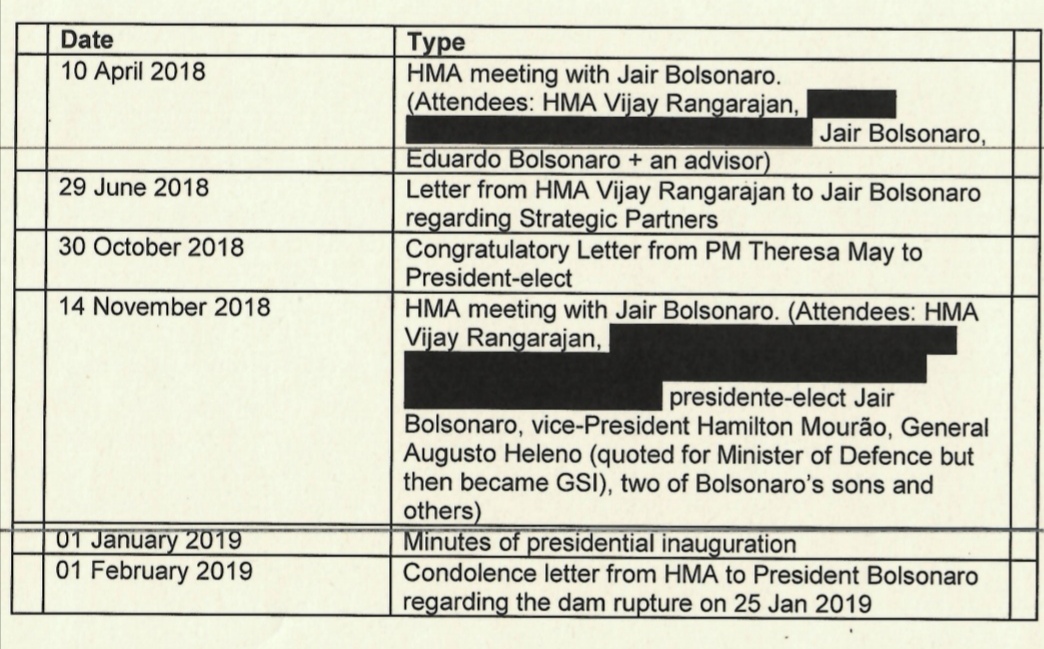

A Freedom of Information request filed in July 2019 can now reveal meetings between British officials and the Bolsonaro presidential campaign in the months running up to the 2018 presidential election.

On 10 April 2018, six months before the election, UK ambassador Vijay Rangarajan met with Jair Bolsonaro, his son and congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, and an unnamed advisor. On the UK side, at least one name is fully redacted. Though full minutes of the discussions were requested under the Freedom of Information Act, the FCO has failed to provide anything more than a skeleton outline of the meetings.

Yet revealingly, on 9 April 2018, then-Chief Secretary to the Treasury Liz Truss set off for Brazil on an official visit to talk “free trade, free markets and post-Brexit opportunities”. On 10 April, the day of the meeting with the Bolsonaro campaign, British diplomat Chetna Patel tweeted that she was “delighted” to be welcoming Truss to Brazil, tagging ambassador Rangarajan. Truss and Rangarajan, it appears, were both together in Sao Paulo on the day of the ambassador’s meeting with the Bolsonaro campaign.

At the time of publication, Truss’ office has not replied to a right of reply offered concerning the meeting.

“As we leave the European Union and establish an independent trade policy”, said Truss prior to her visit to Brazil, “we will be able to negotiate new trade agreements with major trading partners, like Brazil and Chile” A former Shell employee, Truss also visited the Shell Research Centre for Gas Innovation in Sao Paulo, “where the UK has collaborated… on a number of projects”.

Truss’ likely presence at a meeting with the Bolsonaro campaign in April 2018 gains significance in light of the UK government’s consistent lack of transparency surrounding her visit. A full eight months after filing a Freedom of Information request in August 2019, the British Cabinet Office seems no closer to revealing any information about Truss’ activities in Brazil during 2018.

Environmental deregulation

Based on her past endeavors, Truss seems to be one of the government’s favored diplomats when negotiating trade deals which undermine both democracy and global climate action. Indeed, Truss now works in the same Department for International Trade which was caught secretly lobbying the “Brazilian government on behalf of BP and Shell” in 2017 with regards to environmental deregulation.

According to a Department for International Trade job vacancy advert published in 2018 by the FCO, the department’s key objectives in Brazil were to “promote UK business in Brazil”, “drive UK commercial success” and, notably, “lead efforts in Brazil on improving Market Access” by removing “barriers to trade”. The “desirable qualifications” of the prospective candidate included “market access/lobbying” and “trade policy”.

In recent years, Truss has received donations of over £8,000 from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), which has been described by Greenpeace as “an avid opponent of the Kyoto protocol, as well as most other environmental regulations”, and its board of trustees have included ExxonMobil CEO Lee Raymond.

The donation, by far her largest in recent years, was for Truss to speak at the annual AEI World Forum in 2019, “a highly secretive meeting organized by the most influential neoconservative think tank in Washington”. Over recent years, the AEI has supported Dilma Rousseff’s illegitimate impeachment, promoted Bolsonaro and cheer-led the now thoroughly discredited Lava Jato taskforce.

While in Brazil, Truss also met with representatives of the Instituto Millenium, a right-wing, climate breakdown-denying think tank co-founded by Bolsonaro’s finance minister Paulo Guedes.

Truss later appointed advisors Nerissa Chesterfield from Think Tank Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), and Sophie Jarvis of the Adam Smith Institute, which is linked to Instituto Millenium. Both of these organisations are part of the Atlas Network, a Koch-funded Libertarian international which campaigned for the ouster of Dilma Rousseff in the “soft” coup of 2016. The UK Government identifies Adam Smith as a fundamental tool of the country’s influence abroad, a means by which it promotes free market economics and small government in the developing world and enables “the projection of soft power directly through the UK’s ability to influence policy in these countries”.

During the election, Bolsonaro’s own team and his sons wore shirts bearing the face of Margaret Thatcher, who is lauded by such Libertarian think tanks as an example to the world.

Truss’ favored solution to climate breakdown in Brazil seems akin to that of the Bolsonaro government. In October 2019, Truss was asked by Scottish National Party MP Martyn Day about the “illegal deforestation [that] takes place in the [Brazilian] Amazon rainforest – something that the Paris agreement explicitly sets out to tackle and reduce”.

Truss responded: “I am a great believer that free trade and free enterprise help us to achieve our environmental goals through better technology, more innovation and more ingenuity”.

If Truss attended meetings with the Bolsonaro campaign in April 2018 on a trip to promote UK trade, why is the UK government refusing to reveal any details, let alone acknowledge her presence there?

Rangarajan’s busy embassy

Other UK meetings and correspondence with the Bolsonaro campaign can also be revealed.

On 29 June 2018, Rangarajan sent a letter to Jair Bolsonaro regarding “Strategic Partners”. Details withheld.

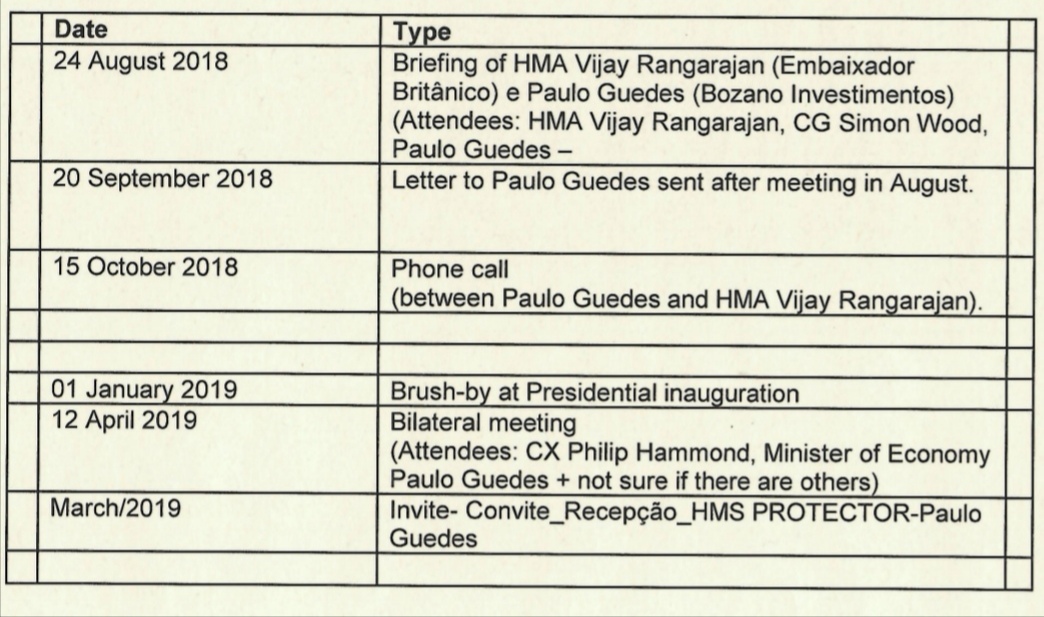

On 24 August 2018, Rangarajan was briefed by Jair Bolsonaro’s future Finance Minister Paulo Guedes, in the presence of Consul General Simon Wood. Details withheld.

On 20 September 2018, Rangarajan sent Paulo Guedes a letter regarding their meeting in August. Details withheld.

On 15 October 2018, Rangarajan and Paulo Guedes had a phone conversation. Details withheld.

Jair Bolsonaro would go on to be elected on 28 October 2018 in a runoff against the centre-left former São Paulo Mayor Fernando Haddad of the Workers Party (PT), a replacement candidate for the jailed former President Lula da Silva.

Post-election

The UK government’s ties with the Bolsonaro government have continued since his election.

On 14 November 2018, Rangarajan again met with President elect Jair Bolsonaro, vice-president elect Hamilton Mourão, General Augusto Heleno (head of the cabinet for institutional security, or GSI), two of Bolsonaro’s unspecified sons, and other unnamed individuals. Details withheld.

On 19 August 2019, as the Brazilian Amazon burned, UK trade minister Conor Burns was in Río de Janeiro to meet the state’s governor, Wilson Witzel. Under Witzel’s governorship, Río has suffered a campaign of police terror; police killings there in 2018 numbered 8.9 per 100,000 habitants – higher than the total homicide rate of almost any US state that year. Witzel was elected in October of that year and, during 2019, police killings in Rio still reached a record high – a total of 1,810, or five per day.

Documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) can reveal that Burns praised Witzel’s “ambition for reducing violence” in Rio and promised that the “UK stood ready to work together on a range of issues, including security [emphasis added]”. Security co-operation between the UK and Brazil, the documents further revealed, includes biometric facial recognition cameras.

Bolsonaro, meanwhile, has proven a lucrative president for UK interests. By 2018, Shell and BP — with whom the UK ambassador to Brazil has met over twenty times since 2017 — had already accumulated 13.5 billion barrels of Brazil’s oil, more than the country’s own company Petrobras, and for only a fraction of the cost.

British companies have also invested heavily in biofuels. BP owns the largest biofuel plant in Brazil, and Shell has many investments such as the Raízen biofuels joint venture. Long depicted as environmentally friendly, biofuel production is in fact responsible for deforestation and pollution and its heavy use of resources contributed to the São Paulo water crisis of 2014, which caused mass shortages for the population at large.

On March 20 2020, Mongabay reported that British mining giant Anglo American has made over 300 requests for permission to explore 18 indigenous territories in the Amazon, some of which are home to uncontacted peoples. This is the latest in a transnational scramble to exploit the region since Jair Bolsonaro came to power, and the President has just sent a bill to Congress which will authorise the expoitation of indigenous lands, something threatened long before his election. For this, Bolsonaro is being accused of genocide.

These alarming new disclosures on UK-Brazil relations must be considered in the broader context of UK Foreign Policy in Latin America. Emily Bell, Senior Lecturer in British Studies at the Université de Savoie, observes that the UK’s soft power is now exercised “increasingly via large companies which promote British economic and political interests through corporate imperialism.”

The contents of discussions between UK officials and the Bolsonaro campaign in the months leading up to October 2018 merit thorough scrutiny.

Not only does the UK government’s collaboration with the rise of the Brazilian far-right throw unequivocal shade on its pretence of supporting ‘human rights’ abroad – it is a matter for those in Brazil concerned with the maintenance and sovereignty of their own natural resources.

[qpp]