By John McEvoy

Exclusive. Recently declassified documents reveal Britain’s enthusiastic support for Brazil’s 1964-85 dictatorship. Racist and colonial in tone, the files expose a secret propaganda unit infiltrating opposition media, and further evidence of covert training in torture.

The ‘assiduous cultivation’ of Samuel Wainer

In a 1969 file entitled ‘Information Research Department: operations in Brazil’, declassified only in December 2019, Foreign Office official E.R. Allott discusses Britain’s role in keeping the Brazilian armed forces ‘informed about Communist policies and methods, with a view to making its opposition to Communism rational and well-informed’. Though the imagined communist threat had subsided with the military coup of 1964, British planners remained nonetheless concerned, in characteristically racist terms, that the Brazilian ‘masses… are capable of being worked up quite easily by a skillful demagogue and, being descendants of slaves, they have an understandable liking for paternal authority’.

From the embassy in Rio de Janeiro, British officials thus devised a propaganda offensive to keep communism in the docks and cultivate the wider left-wing movements in Brazil. This campaign would be operated by the Information Research Department (IRD), the UK Foreign Office’s secretive Cold War propaganda unit.

‘It is necessary to regard the Revolution [in 1964 as] the end of a chapter. The immediate IRD objective is achieved’, wrote a British official from the embassy in Rio de Janeiro. ‘If the work is to continue, a fresh approach is necessary based on longer-term objectives; and the network of contacts will have to be reconstructed on the back of what remains viable, effective and co-operative’.

One of the earliest and chief targets of this operation was Ultima Hora, a mainstream, left-wing Brazilian newspaper founded in 1951 by journalist and author Samuel Wainer. During the 1960s, Ultima Hora’s circulation was roughly 350,000, with 12 regional editions and, in 1954, a record of 800,000 for its edition announcing the death of President Getúlio Vargas.

Wainer remains a hero in Brazil. From the 1950s to his death in 1980, he was a hugely influential figure in the Brazilian media, on the Brazilian left, and prominent in popular culture through his wife Danuza Leão, a journalist, model, and sister of Bossa Nova artist Nara Leão, who was a member of Brazil’s communist party, the PCB.

In 1964, Ultima Hora was the only mainstream newspaper to defend the government of João Goulart and oppose the military coup. Wainer’s brave editorial decisions during this period are still fondly recalled, as are his resistance to dictatorship, and stories of personal intervention to save journalists from arrest, torture or murder at the hands of the secret police.

Ultima Hora was the only major newspaper to outright oppose the US-backed 1964 coup against President João Goulart.

Ultima Hora’s hostility to the dictatorship was recognised by British planners, who noted that the newspaper had been temporarily ‘closed down by the government at the time’ of the coup and that its editor ‘Samuel Wainer escaped… when repressive action was… taken against the Brazilian newspapers’. [FCO 95/491] Wainer remained exiled from Brazil until 1967.

Ultima Hora thus posed both a threat and an opportunity for British planners. If Wainer could be nurtured by British officials, the newspaper’s radical edge could be blunted while its reputation could be leveraged on behalf of British interests.

Attempts to influence Ultima Hora began within six months of the coup. In a letter sent from IRD Field Officer R.J.D Evans to IRD official JE Jackson dated 30 September 1964, Evans discussed ‘unofficial arrangements’ for IRD meetings with ‘the directors of the Jornal do Brasil and a vice-president and editor of Ultima Hora’.

By 1968, British officials in Brazil boasted that the nurturing of Ultima Hora was a fait accompli: Britain’s IRD officer R.A. Wellington had, they claimed, effectively encouraged Wainer to take the teeth out of Ultima Hora’s radicalism.

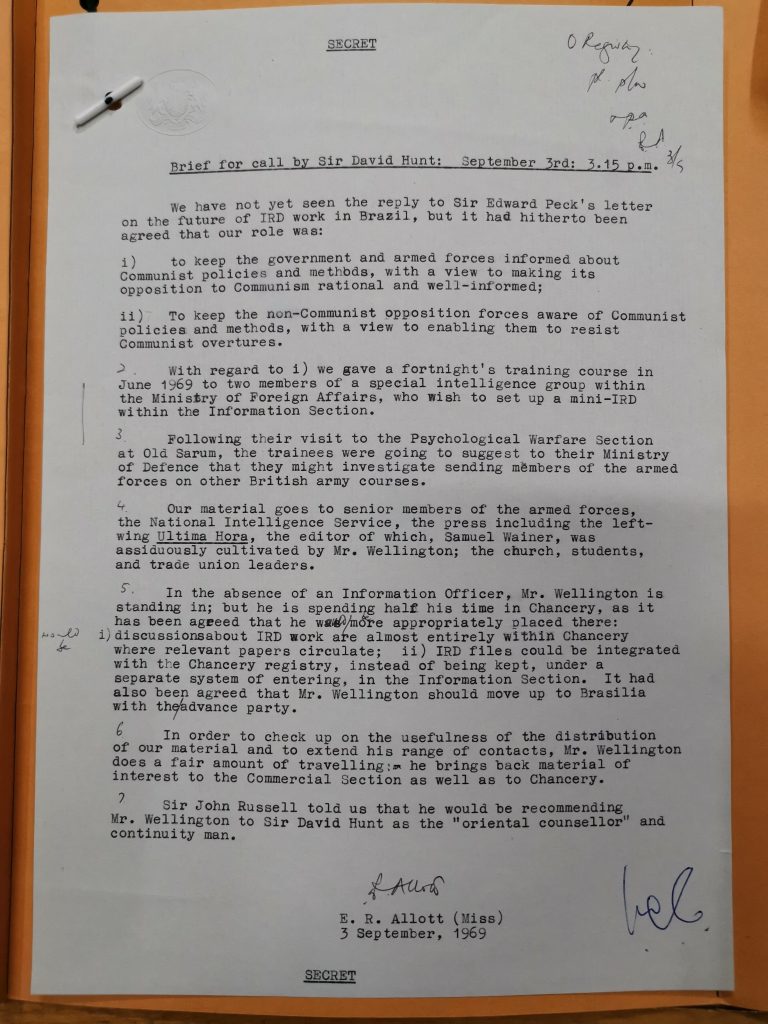

As the declassified file reads, ‘Our [IRD] material goes to senior members of the armed forces, the National Intelligence Service, the press including the left-wing Ultima Hora, the editor of which, Samuel Wainer, was assiduously cultivated by Mr. Wellington; the church, students, and trade union leaders’.

IRD officials would curry favour with influential figures like Wainer through unofficial meetings, lunches, and outings, during which subtle suggestions and recommendations would be passed on. Another avenue for gaining influence was passing on sensitive, newsworthy material, often gained from the British secret services.

The 1969 UK Government document, declassified in December 2019, reveals the IRD’s ‘assiduous cultivation’ of Samuel Wainer

Wellington had been appointed by the British embassy in Brazil in May 1963 with the ‘central priority’ to ‘investigate the gaps’ in the ‘flow of anti-Communist propaganda material reaching the Press, Radio Stations’. Wellington was also instructed to ‘concentrate… on the personal contacts which he has already made’ in the country. [FO 1110/1623]

By 1969, British officials were satisfied that Wainer had been successfully worked on. ‘The transformation of Ultima Hora from a quasi-communist, extreme left, newspaper into a respectable and respected opposition daily’, reads another declassified document, ‘has been helped by the special relationship between the IRD officer and the newspaper founder and president, Dr. Samuel Wainer’.

A Royal Visit

While it is impossible to quantify the impact that British officials had on Ultima Hora’s output, they privately boasted that it had been significant.

One file notes that ‘the supplement produced at the time of the visit of H.M. the Queen by Ultima Hora was considered to be the best produced by any Brazilian newspaper and the Americans even asked us how much we had paid the newspaper for it. Not a penny, is of course the answer’. [FO 95/491]

In November 1968, Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip had led the British Monarchy’s first official state visit to the country. The state visit has been called ‘the ultimate weapon’ of UK diplomacy. Britain’s head of state would not return after democracy was eventually restored in the 1980s.

Greeted by General Artur da Costa e Silva, the second of five dictators who followed the US-backed Military Coup four years previously, the royal couple took in the sights of Brasilia, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, carefully shown evidence of the supposed Brazilian ‘economic miracle’. The narrative was that Brazil had been ‘saved from the disaster of communism’ in 1964 – something believed to this day by president Jair Bolsonaro and his supporters.

With his regime still bathing in the glow of the royal visit, just weeks later Costa e Silva would implement the notorious Institutional Act Number 5.

The societal effects of neo-fascist “coup within the coup” AI-5 still haunt the country today. AI-5 abolished habeas corpus, and turned an already repressive dictatorship into a hell of political persecution, corruption, censorship, torture and genocide. The barbarity intensified still under Costa e Silva’s successor, General Emílio Médici.Médici’s rule was famous for its slogan “Brazil: Love it or leave it”, which taunted regime opponents, artists and intellectuals driven by fear into exile, such as Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, who escaped, ironically, to London.

Yet the degenerating human rights situation in Brazil evidently did not concern the British.

In his annual review from December 1972, UK ambassador to Brazil David Hunt was dismissive of human rights concerns in Brazil. Absolving leadership, he blamed poor policing and bad foreign press, malicious organisations such as Amnesty International, and gave his enthusiastic support to the bloody rule of Médici, calling him ‘a genuinely popular President who is patently honest and sincere in his desire to promote the welfare of every section of the Brazilian people’.

Writing in 1970, British defence attaché P.B. Winstanley concluded: ‘Despite the obtuse apathy of the people, the country is advancing as fast as, perhaps, the nature of its mulato millions will allow’.

Wainer eventually sold Ultima Hora to the Folha group in 1971, and passed away in 1980. It was not possible to find a spokesperson for Ultima Hora at the time of this article’s publication.

British penetration of the Brazilian media during the dictatorship has eluded almost all scholarly attention, with the notable exception of Brazilian journalist Geraldo Cantarino’s books ‘Segredos da propaganda anticomunista’ and ‘A ditadura que o inglês viu’.

‘Psychological Warfare’

The files also detail how Britain provided ‘a fortnight’s training courses in June 1969 to two members of a special intelligence group within the [Brazilian] Ministry of Foreign Affairs’. Notably, the file notes that this training course was conducted within the ‘Psychological Warfare Section’ of the Old Sarum Airfield in Wiltshire.

‘Following their visit to the Psychological Warfare Section at Old Sarum’, the file reads, ‘the [Brazilian] trainees were going to suggest to their Ministry of Defence that they might investigate sending members of the armed forces on other British army courses’.

This subject of UK torture training in Brazil was explored in detail in ‘Segredos de Estado. O Governo Britânico e a Tortura no Brasil. 1969-1976′ by João Roberto Martins Filho.

British military training to the Brazilian dictatorship was thought to have begun during the late 1960s, when the Brazilian military developed ‘sophisticated methods of interrogation [also known as torture]… influenced by suggestions and advice emanating’ from the British military. The exact location, however, is revealed in the recently declassified file.

According to leaked documents from the Joint Warfare Establishment at Old Sarum, ‘the primary aim of Psychological Warfare operations is to support the efforts of all other measures, military and political, against an enemy to weaken his will to continue hostilities and reduce his capacity to wage war… It can be directed against the dominating political party in the enemy country, the government and/or against the population as a whole, or particular elements of it’.

Indeed, psychological warfare was used against wide sections of the Brazilian population. In 2014, a Truth Commission found that ‘Under the [Brazilian] military dictatorship, repression and the elimination of political opposition was because of the policy of the state, conceived and implemented based on decisions by the president of the republic and military ministers’. During this period, 191 people were killed, 243 ‘disappeared’, and many more were tortured. Unofficial figures are significantly higher. And this policy, as the declassified documents evidence, was partly informed by British government advice.

British support for Bolsonaro

This evident British desire for Brazil’s neo-fascist dictatorship to continue and flourish have parallels in the present.

In 1972, former Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Sir Alec Douglas-Home wrote with glee that leftist opposition in Brazil had been all but eliminated, and expressed optimism about what he called a ‘benevolent dictatorship’ which would continue for ‘many years to come’.

‘It seems more than probable that by 2030’, he continued, ‘before today’s students reach eighty years of age, Brazil will indeed have transformed herself into that ‘country of the future’ for which so many generations of Brazilians have sought in vain’. Hunt’s predecessor, Ambassador Sir John Russell had earlier concluded that: ‘The Brazilians are still a tremendously second-rate people: but it is equally obvious that they are on their way to a first-rate future’.

Today, Brazil is once again under an authoritarian, far-right government – now headed by neo-fascist Jair Bolsonaro, who considers the dictatorship a golden age, and once described the fifth and final of those dictators, João Figueiredo, as the “last real president” of his country.

Bolsonaro faces multiple requests for investigation at the International criminal court in the Hague for “incitement to genocide and widespread systematic attacks against indigenous peoples”. This was before his response to the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in 65,000 deaths and counting.

A number of Freedom of Information requests have revealed evidence of continued British support for the Brazilian far-right president. Secret meetings, for instance, were held between British officials and Bolsonaro before, during, and after the Brazilian 2018 election campaign, with a Bolsonaro government offering clear advantages to British interests. The redacted list of names attending these meetings included his sons, his economy minister Paulo Guedes, and the military core of his eventual government.

Evidence of British manipulation of the media, and particularly its targeting of left-wing journalists and progressive editors, is likely to cause consternation in both Brazil and Britain itself.

Indeed, the British security service’s ‘neutralisation’ of the Guardian in recent years suggests these practices are far from dead.

[qpp]