By Graham Douglas for Sounds and Colours.

It was a hot day in the beautiful town of Amarante, the Portuguese base of Brazil’s MIMO festival. I’m chatting to Otto prior to his show at Parque Ribeirinho in the evening and a day after seeing him talk at a forum about the state of new Brazilian music. We begin chatting about the rich and poor in Brazil. He says people are strangling each other, and while politics is not necessary for the rich, the people need it to ensure adequate social programs.

It’s been a convulsive period for Brazilian politics, and as a result it’s a topic which has become more and more important in Otto’s music – not sloganeering party-politics, but the politics of a loving society. This is reflected in Otto’s latest album, Ottomatopeia, his sixth studio album in a career that began with him playing percussion in manguebit pioneers Mundo Livre S/A before seeing his solo career ignite with early single “Bob” in 1998.

Brazilian music has many intertwined traditions, “we are all mixed and re-mixed” he says, and of his own multi-ethnic background he adds: “I’ve turned out taking advantage of this”. The musician still thinks about the manguebit image of the crab rising out of the mud of Pernambuco with its antennae tuning in to the larger world, both transmitting and receiving. The cycle of life and death goes on, and Otto is becoming more reflective as he passes 50.

I was at the Ideas Forum yesterday [a discussion on “The Current Sound of Urban Brazilian Music” at MIMO] and remember you saying that the middle class in Brazil don’t want equality.

Of course, you see how Lula was convicted without proof. It was a judicial coup.

He talks about the movie Churchill, Chamberlain said “Churchill won with the English language, he convinced the people that they should fight against Germany because it is not possible to make a peace agreement with blood-thirsty men”. It was the English language that made him win. In Brazil, the only one who can talk to all the people is arrested, incarcerated. He can’t even give interviews. And he is the most accepted candidate.

The judge Moro was biased in the trials of Lula and Dilma. It’s the influence of the US. Huge amounts of money can be found to build stadiums for the World Cup, even when they are over-priced, but not to invest in public housing. Brazil is paying for this.

Talking about your music, you said that you consider the new album to be a more mature and also more political phase of your work.

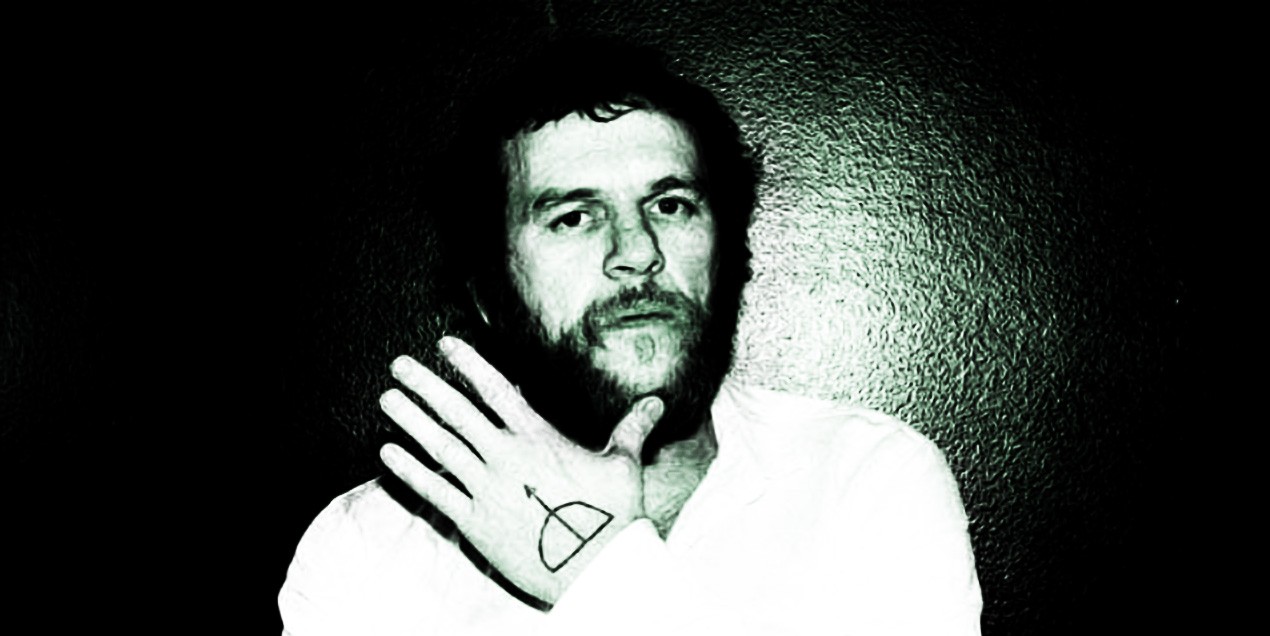

Beginning with the impeachment of Dilma, for two years I, like most people, didn’t know how to respond, but my kind of politics is about feelings, not about producing pamphlets. I wanted to talk about things like the mental torture people are suffering, the feelings of people. In Brazil, the press is completely venal, it can be bought and sold, politicians are completely corrupt. So, in this disc I wanted to remind people by using the theme of torture, because we have an extreme right candidate, Bolsonaro [who is now the President-Elect]. I took photos of torture instruments. But I think principally about our feelings, not just people on the left, because when democracy is trampled on everyone suffers, even the elite. People are very pessimistic, and the media are full of lies. This record is a cry against all this. I’m 50 now and I want to express my feeling of being Brazilian, to speak about love.

You said yesterday, that love is not just a personal thing but a bigger concept that works socially.

I work a lot on feelings, they are important. Of course, in the contemporary world, the speed of feelings, I use that a lot.

Many artists say that its difficult to mix politics with art.

My idols, like Chico Buarque, Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, all of them composed political texts, during the dictatorship. They are my “artistic DNA”. They experienced the repression, so I don’t agree that Brazilian music is apolitical. These people reflected the absurdity of the repression of rights.

Like Chico’s song “Calice”.

Modern dictatorships are different, they are more mixed up with commerce now. It’s not about the army so much. Now a company that wants to make money from water makes sure that a Deputy is elected who will give permission to divert a river, it’s completely destructive. This happened where I live, they blocked a river to sell the water to other places. And they can build a super-shopping centre with security in the historic centre for the middle class, but the people in general lose out. Business is destroying people.

In the end we can’t eat money…

The market for meat, food, these gigantic farms, the market is corrupt.

Yesterday you talked about the problems for a musician in getting their work known to an audience they want to reach – that something recorded in Pernambuco gets processed in São Paulo.

I was talking about the interior of the north-east, which is already fragile, the cinemas and the concert halls have gone. The producer has the power, and this is affecting the whole of Brazil.

You said making your 2009 album was a kind of therapy after a separation.

I turned to literature and cinema during that period, and when I found Kafka – the cockroach in Metamorphosis, and the character not knowing what is happening to him.

The cockroach reminds me of the image of the crab in the mud of the manguebit movement.

The cycle of man as a crab – men shit and the crab arises from that. I’m getting older, and I appreciate the cycle of life, and I feel more contented.

You played in France for a couple of years around 1990, even in the Paris Metro. How did that impact on the manguebit movement back in Pernambuco?

I think Paris really opened up my perception of the world, of what is universal, and it encouraged me to make a living from my art. Playing in the metro was wonderful, it was my first real contact with the public. The manguebit movement was a gift of experience. It showed me that I couldn’t go back, that art was definitely my foundation in life.

Your ‘idol’ Reginaldo Rossi once said: “The public is an intimate being that we need to commune with.” Yesterday, I saw you come down from the stage to sing in the middle of the crowd – so this saying of Rossi is still a guiding principal?

There is no-one like Rossi when it comes to charisma. I have a very close connection with my audiences. I feel I am a singer who expresses popular desires. I’m still romantic, and I have an audience that is very cool, very respectful, and, the most important, they understand me completely, maybe even more than I do myself. I sing about contemporary feelings, I write to liberate, to think. When I go on stage, I feel a desire that is beyond my control.

Brazilian music has always been multicultural, so does it make sense to talk about a Brazilian or a Pernambucan Tradition, or rather about many traditions that continue developing?

Traditions exist together with the way the people have developed, it has a history and an identity. In my case, I know that it can bring me what is new, contemporary. I never have to force it to happen, because I know that it’s intertwined in my soul. You have to let it flow, that’s how it is for me. I live much more in the ethnic roots, in the mixture of peoples and in their migrations. The world mixes everything. We are mixed and re-mixed. I’ve come out taking advantage of this… laughs.

How do you see your music evolving in the age of the internet? Is there a danger of losing contact with your audiences?

I’m an internet enthusiast, I think it is always going to help civilization, the contact won’t be lost, now God is digital. The transformation is only just beginning. My audience is getting bigger with it, and independence begins with it. Freedom.

Have you got another project on the go?

My next project is coming from songs composed with the garage band, all very experimental for me. But full of poetry and music. Maybe the name of the next disc will be Vernaculos.

[qpp]