Podem me prender, podem me bater / Podem até deixar-me sem comer / Que eu não mudo de opinião

They could arrest me, they could beat me / They could even leave me starving / I wouldn’t change my opinion

Opinião – Nara Leão 1964

In March 2014 a group of students at the School of Law in the University of São Paulo invaded the classroom of professor, singing the title song from Nara Leão’s 1964 second album Opinião de Nara. Their reason? He had given a statement on the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Coup, describing it as an anti-communist revolution.

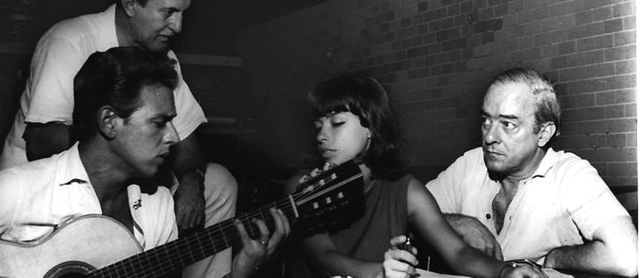

Nara Leão was born Espírito Santo, Vitória in 1942, her family soon moved to Rio de Janeiro. As a teenager Leão was an instrumental part of the development of Bossa Nova with her family Apartment in Copacabana used as a base for early experimentation. Most of the era’s greats participated in the gatherings including, Vinicius de Morais, Roberto Menescal, Carlos Lyra, Sérgio Mendes and boyfriend Ronaldo Bôscoli.

Left to right – Carlos Lyra, Elenco Records founder Aloysio de Oliveira, Nara Leão and Vinicius de Morais

Bossa Nova is often seen as a light, simple music but nothing could be further from the truth. Not only is the music deeply complex in structure and it is also a consolidation of social values of the time. Bossa was very much a product of Brasil’s European descended middle class, but it followed with the cultural tendencies of the era. Bossa searched for a new music that was specifically Brazilian by mixing Samba’s syncopated rhythms and European vocal treatments. But also by the standards of the day the restrained vocal delivery was a break from popular music. Middle class culture had been Eurocentric and derivative, Bossa was the direct offspring of the Vargas era formalisation of Brasil’s African heritage.

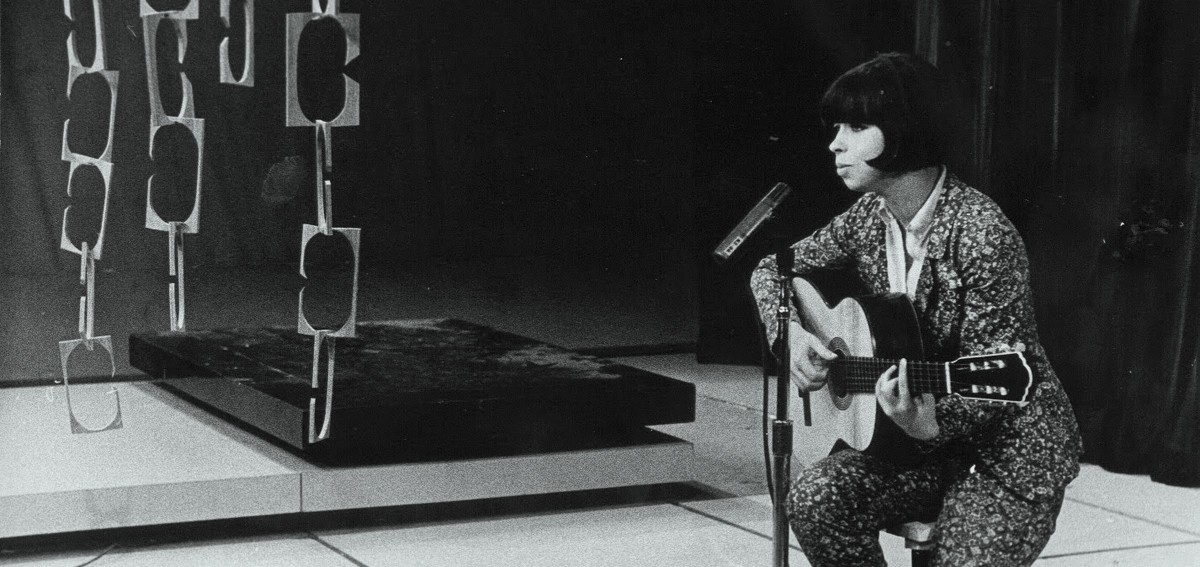

Leão is often dismissively described as the “Muse of Bossa Nova“. The Brazilian press frequently attribute “muse” to successful women in cultural life, inadvertently diminishing women’s contribution to society. The case of Leão possibly because it is far easier for Brazil’s conservative media organisations to discuss her as a pretty, young woman than as a singer politicised at an early age by the inequality she saw around her.

One common aspect of the Brazilian Media is the adoration of cultural figures who’s political views they detest. It is not an exaggeration to say that most of Brasil’s important cultural, literary and musical figures were, and are on the left of the political spectrum – although that does not mean they necessarily support the current Workers’ Party administration -. Brasil’s cultural class’ affiliation to leftwing causes has often been more utopian and romantic than dogma and party political, Oscar Niemeyer’s lifelong communism being a case point.

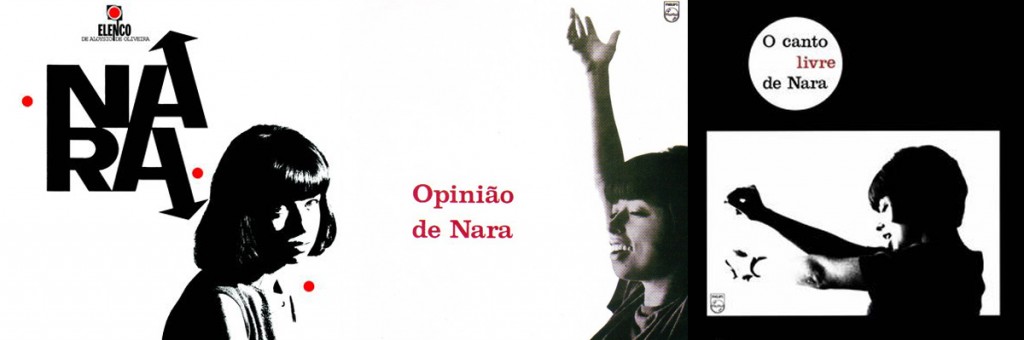

Nara Leão’s first three album covers

Leão’s first three albums in particular show a rapid rise from elegant Bossa Nova to music that was radical both lyricaly and sonically. Like many preformers of the time she worked mostly with songs either written for her or traditional Brazilian laments. Leão’s first album Nara was released on the iconic Elenco Records label in February 1964 and already gave an idea was what was to come next. Although the album contained songs from writers such as Lyra and Morais it also included a samba de morro lament by Samba composer and singer Zé Keti -Leão would later go on to develop a anti dictatorship stage show . This was regarded as controversial at the time; Brasil was a much more unequal and divided country in the 1960s and a young middle class white woman singing a black protest song was unheard of.

Later in September six months after the Coup, Leão released her second album on Philips Opinião de Nara with it’s opening lines a full broadside against Brasil’s new military rulers, They could arrest me, they could beat me, They could even leave me starving, I wouldn’t change my opinion. During the period of the album’s release Leão publicly expressed that in the face of dictatorship Bossa Nova was dead and singing about a O Amor, o Sorriso e a Flor was redundant.

Leão’s music was not just lyrically important but musically, no more so than on her third album 1965’s O Canto Lirve de Nara. Again she interpreted songs by some of the musical leaders of the day including band leader Dorival Caymmi, lyricist Vinícius de Moraes and composer Zé Keti. One particular song by Caymmi Suíte dos Pescadores contains choral arrangements that wouldn’t sound out of place in a Philip Glass composition, this was not “elevator music”. It is a beautifully rhythmical and harmonically complex album that was ahead of it’s time.

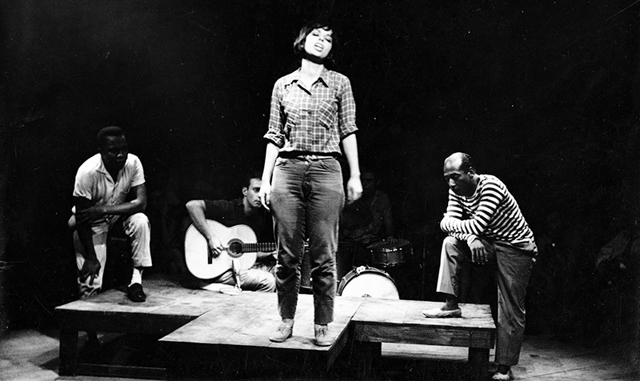

The concept of Opinião was loosely developed into a stage show, Show Opinião in late 1964 by Rio de Janeiro’s Centro Popular de Cultura. The military quickly cracked down on progressive cultural organisations shutting Centro Popular de Cultura but members still managed to put together events subverting new military censorship. The early years of the regime were less violent and open than before Ato Institucional Número Cinco (Institutional Act Number Five) of 1968 suspended all political rights, including ending Habeas Corpus for perceived political crimes. Luckily Show Opinião made it to stage before the censors stepped in. Show Opinião is regarded as one of the most important moments in Música Popular Brasileira (MPB) when Brasil’s deep social problems were confronted head on by artists, even at the risk of arrest.

Show Opinião – Nara Leão onstage with João do Vale and Zé Keti

Leão further distanced herself from Bossa Nova with the inclusion of her song Lindonéia on the Tropicália album Tropicalia ou Panis et Circencis. Tropicália was a movement that aimed to break from the rigid positions that had come to dominate Brazilian intellectual discourse following the coup. But at its core Tropicália was a return to earlier ideas and theories of Brazilian intellectuals like Gilberto Freyre, Sérgio Buarque de Holanda and Oswald de Andrade and who’s Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibal Manifesto) is returned to over and over in Brasil’s post colonial culture.

Like many of her peers Leão took voluntary exile as the oppression of the military rulers increased. Perhaps worn down by the years of the dictatorship or the pressures of parenthood, after the 1960s Leão’s work mostly returned to Bossa Nova and MPB. But her early albums and performances left Brasil with a body of work that defined the anger many Brazilians felt as an undemocratic regime became entrenched, wounding Brasil up until today.

[qpp]