Brasil’s Education crisis is not a crisis, it is a project. – Darcy Ribeiro.

Across the political spectrum Brazilians will tell you that the principal problem in the country is education, yet who profits most from programmed, weaponised ignorance? Research, science, technology, culture, and education are not ideologies, but approaches and attitudes toward them in Brasil’s two bitterly opposed models of governance – Desenvolvimentismo and Entreguismo – come to the fore during moments of national angst like these.

The 200 year old Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro is both a symbol of Brasil’s history, and its chronic neglect of that history.

As the building burned on the evening of Sunday 2nd September, like the horrific Paysandu fire before it, the Museum quickly became a ghastly symbol of a pessimistic post-coup Brasil.

Yet its destruction follows that of a myriad of museums and historic buildings over past decades, such as São Paulo’s Instituto Butantã, Museu da Língua Portuguesa, Memorial da America Latina, Escola de Artes e Ofícios, and Museu do Ipiranga.

An important research facility, and former palace of the Brasilian imperial family, it is the oldest scientific institution in the country and home to much of Brasil’s cultural heritage. It housed some of the finest collections of South American history and pre-history. Most of the 20 million items it contained were reduced to ashes, including Luiza, the oldest human fossil found in Brasil, and the oldest human remains ever found in the Americas. Four frescoes from Pompeii’s Temple of Isis were also lost to the fire.

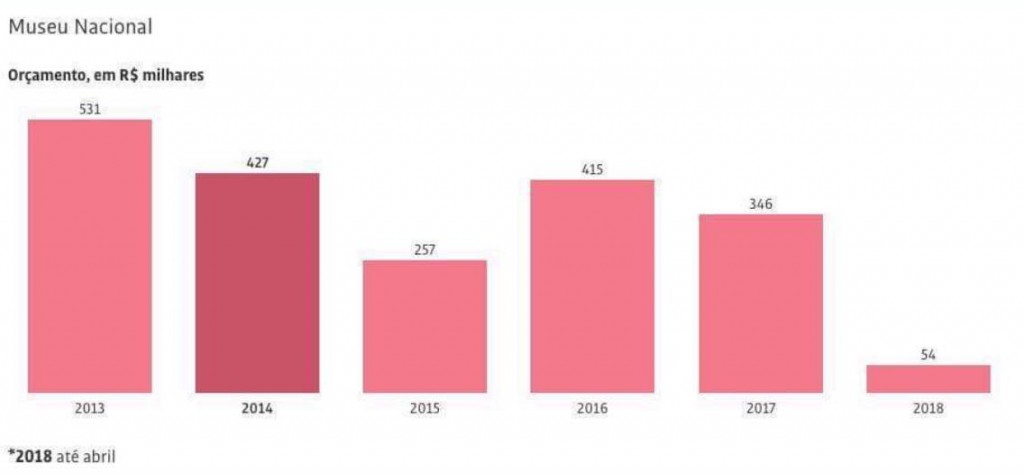

The blaze has left staff “devastated beyond comprehension”. Earlier in 2018 its director issued a grave warning that the facility now only had sufficient budget for “palliative measures” for the crumbling museum. A short time ago a budget had been allocated specifically for renovation and installation of fire prevention systems. The money disappeared into the black hole of local government.

While Rio de Janeiro’s brand new waterfront “Museum of Tomorrow” received millions in investment, the culturally, educationally and scientifically far more important National Museum struggled to cope on a shoestring. The annual budget for maintenance of the museum is 520 thousand reais, about 140,000 US dollars, whilst a federal judge earns 600 thousand reais a year, equivalent to US 150,000. This gives an idea of how savage the conditions of culture and science in Brasil now are. President Temer has continually raised Judges salaries since coming to power, and has been protected by the same Judiciary.

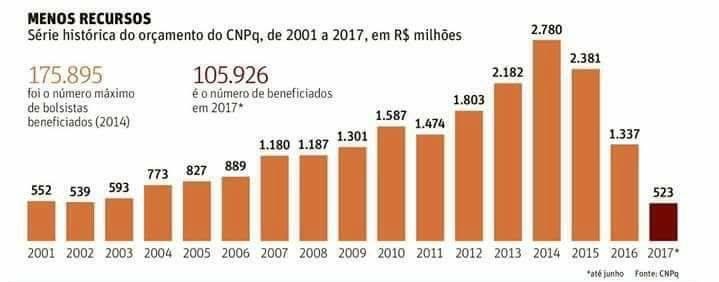

Government funding for National Council for Scientific and Technological Development 2001-2017

As the scale of the fire became clear, Carioca comedian Gregorio Duvivier invoked Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, and its symbolism of fire and knowledge.

TV Globo presenter Alexandres Garcia invoked “rewriting history and burning the evidence”, yet it was unclear at whom his accusation was directed considering the organisation supported both Temer’s austerity programme and a military dictatorship notorious for its erasure of history. A Globo editorial also urged against “politicising” the disaster. Readers rightly asked how that could that be possible when the fire was borne of long term neglect, which had been exacerbated by Temer’s savage cuts to education, research and culture funding – rapidly wrought by his post-coup administration in 2016. This museum ablaze was distilled politics.

To the left the fire was a demoralising symbol of the coup, and Temer’s “programmed decay” caught in freeze frame.

Conservatives too sought to politicise the disaster, and blamed the previous governments of Lula and Dilma. Advocates of the minimal state and enthusiastic supporters of austerity also attempted to make political capital, arguing for the privatisation of cash-starved Federal Universitity of Rio de Janeiro, which operated the Museum.

Museu Nacional budget 2013-2018 (Note: 2015 figure was subject to 3 month congressional budget freeze, 2018 figure is until April only)

Meanwhile, Brasil’s infamous Isentistas suggested that “we are all to blame”. An article from 2004 warning of potential fire risk was evidence that all previous administrations bore equal responsibility, yet this hypothesis did not account for yearly funding increases until 2014. Another journalist drew attention to her work in 1991 on the subject, and yes, the budgetary cuts of the last two years have been far more brutal than anything seen since the era of Fernando Collor. A tragedy foretold indeed.

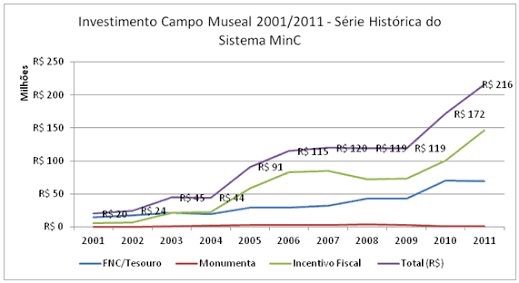

Although neglect does far pre-date the current administration (and that is inclusive of State and Municipal Government, not only Federal), funding for museums in general increased almost 1000% between 2001-2011. An allegation circulating in the aftermath of the fire that Dilma Rousseff bore equal responsibility as Michel Temer due to “cuts” in 2015 raises a crucial passage of history from the collective amnesia of the coup. At that time, though spending was being cut under new Finance Minister, Joaquim Levy, the museum’s funding was frozen because newly elected congressional president Eduardo Cunha, coup plotter and “national saboteur”, had blocked approval of the Governmental budget for three months (which accounted for at least 25% of the museum’s yearly budget). This manouvre was part of the opposition strategy to make it impossible for Rousseff to govern, which was initiated immediately after the 2014 election. The economic effects of this strategy successfully grew public support for her removal.

An actual R$20m plan for reforms to the Museum reached congress around this time and for some reason was never implemented, possibly because of this obstruction, or beyond that due to the freezing of construction projects by Operation Lava Jato. Therefore it can be argued that if we are to blame 2015 budgetary freezes for having contributed to the fire, then it is intrinsically linked with the coup itself, not just the discredited austerity policies that have followed under Temer.

Investment in Brazilian Museums between 2001-2011

During 2016, occupations of Ministry of Culture buildings throughout the country were a high profile front of resistance to the coup, as the incoming administration attempted to shut the department down.

With science and research funding decimated, culture disregarded and education investment frozen for 20 years under PEC241 – the “end of the world amendment” – it is entirely justified and understandable for an indignant population to process this tragedy as synonymous with the calamitous direction post-coup Brasil is taking.

Whether this particular horror has any impact politically is another matter entirely: although most have sought to capitalise, of the 2018 candidacies, only the PT and Rede manifestos already had any specific proposals for the protection of Museums.

The following video was made to celebrate the Museum’s 200th birthday.

Museu Nacional // 200 Anos from Capim Filmes on Vimeo.

[qpp]