By Louis Smith and Brasil Wire editors

When Mauricio Macri won the Argentinian general election in 2015 international markets and investors cheered. Rating agency Moodys immediately raised Argentina’s outlook from “stable” to “positive”, JP Morgan lauded the win, dropping risk to 2011 levels. The Financial Times published an article with the typical headline Investors cheer electoral win for Argentina’s Macri. Macri had narrowly won with 51.44% to 48.56% – oddly, unlike with Dilma Rousseff’s win in Brasil few opined whether this was a valid result. Macri’s win can be attributed to his claimed willingness to address Argentina’s inflation and genuine concerns about a perceived rise in crime coming across the border from Paraguay. The Argentina that Macri inherited from his predecessor Christina Fernández de Kircher was certainly entering a slower economic cycle but was by no means on the rocks. Macri won by a slight margin yet immediately started governing like a man with a major mandate from the voters for radical change.

In December 1999 another Presidential candidate ran on a remarkably similar platform to Macri, Fernando de la Rua. The main difference was de la Rua was only to last two years in office. During this era Argentina was in far worse shape than it was in 2015. De la Rua immediately slashed government spending throwing thousands out of work, and as should have been expected this further contracted the economy as demand and sentiment fell. This created a preventable downwards spiral that resulted in the lender of last resort, the International Monetary Fund, throwing a $22bn conditional loan at the Argentine government. Rather than helping Argentina escape the unfolding crisis the loan’s conditions deepened the country’s woes. Later in 2004, the IMF admitted its actions did more harm than good by ignoring the reality on the ground and reverting to flawed theoretical positions. By December 2001 de la Rua had resigned and the government had poured oil on the fire by announcing a “zero deficit budget” paid for yet again by slashing government worker salaries and pensions.

Yet again demand tanked spiking unemployment and seeing Argentines taking to the streets. The resulting government crackdown left 22 dead. Chillingly this week there were signs this could happen again, when police injured 60 people during looting and riots.

By 2002 in Brasil something similar was occurring. The second presidential mandate of Fernando Henrique Cardoso is one of the most misrepresented periods of Brazil’s recent history. Lauded by a Wall Street media with selective memory, it is a fantasy of economic stability and efficient management. Like Carlos Menem before him, the Cardoso Government embarked on an extensive programme of privatisations, including a partial sale of Petrobras and the sale of mining giant Vale, for a fire-sale price that would have made Boris Yeltsin wince. Value and stability of the early Real currency, which then like the Peso was in effect pegged to the dollar, tamed Brazil’s spiralling inflation crisis and played a big part in the popular perception of economic good times which resulted in Cardoso’s first-round victory at the 1998 election. The Real halved in value shortly after, Cardoso sought IMF bailout and governmental policy was adjusted according to IMF stipulations.

The role of the US Government in Brazil during 1998, in particular the US Treasury, is still classified.

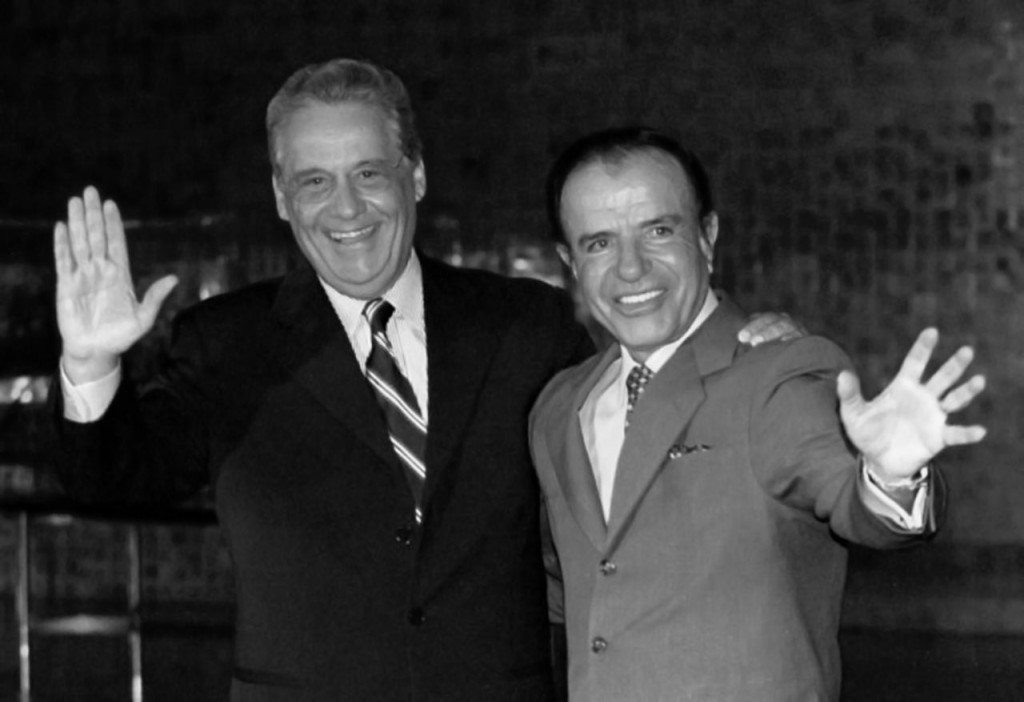

Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Carlos Menem

Jumping forward to the crisis of 2018 the parallels are striking and this time there were clear warnings. Mark Weisbrot co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research said at the time “Given his ideology, there is serious risk of a downward spiral of austerity and recession” and exactly that has happened. Macri entered government during a cyclical cooling and proceeded to strip demand out the economy by bowing to all the same dogmatic economic positions that the IMF admitted had been a failure 15 years ago. This economic policy is driven by the fantasy idea that all government spending is a cost and that the role of markets is not the efficient distribution of goods and services or establishing prices by matching buyers with sellers, but using market forces as a Foucaultian disciplining force on human behaviour. It should be considered that this ideological style of economic theory is not only under attack from reality but from within academia as a new breed of Behavioural Economists refocus Keynes through the lens of 40 years of now failing Hayekian experimentation. This failed economic policy kit is not only propagated by organisations like the IMF and World Bank on emerging markets but over the past ten years has severely changed the face of European countries as well. Whether is it Britain, Brasil or Argentina, stripping demand out the economy reduces growth putting further strain on public finances requiring more borrowing and then more cuts, then more borrowing… On a practical level it does not work, even former UK Conservative ministers can see the writing on the wall.

Beyond the talks of a crisis in Argentina, the numbers show the true face of austerity economics – which in reality is just 1980s market fundamentalism under a new name. When Macri entered office Argentina has stubbornly high inflation at around 27%, it is now pushing 35%. The Peso to the dollar has collapsed as Macri’s request for IMF help has spooked markets in what even Bloomberg is calling an Own Goal. Even more telling, just as in the United Kingdom rather than alleviate public debt the ratio of debt to GDP has ballooned. Tellingly, until very recently Brasil’s oligarchal media was publishing articles like “The Good Example of Argentina“. But the story of the connections between Brasil’s and Argentina’s situation is about more than economic policy. It wasn’t supposed to be like this. In the eyes of International capital and the English language media that serves it, Macri’s Argentina was the herald of a new political dawn in South America, Washington Consensus 2.0, and the end of the so-called “Pink Tide” of centre-left Keynesian governance and sovereign, developmentalist regional integration.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, conservative sectors of the media, Politicians, and the movement to oust elected President Dilma Rousseff breathlessly lauded the Macri example, Argentina was now a shining light, which a competent, “business-friendly” Brazil administration would follow in order to quickly “rescue” its ailing economy, post-impeachment.

This fairytale did not materialise, and the Brazilian Government has just posted minuscule 0.2% GDP growth for the first quarter of 2018. The privatisations, the austerity, the slashing of worker rights have done nothing to improve its economic situation, the deficit has spiralled, unemployment has continued to rise, and the media has all but abandoned any specious notion of recovery since Rousseff was removed in the procedural coup of 2016.

And like Brazil, Argentina’s public discourse is locked in a media loop centred on controversial allegations of corruption against a former President and construction giant Odebrecht, not the dual issues of sovereignty and privatisation that are genuinely key to its future. During 2018, the US military began joint operations on Argentine soil without congressional approval. Early in his Presidency Macri signed a security and defence cooperation agreement that allows for the installation of US bases, of which Southcom plans several, part of a continent-wide expansion of its military presence, which has drawn protest from human rights groups. The Temer government followed suit by opening up the Brazilian Amazon for US-led joint exercises, considered drills for a hypothetical future conflict with Venezuela, which was a pre-coup ally. It is also leasing the Alcântara rocket base to the US military.

Most controversial is the base planned in northern Argentina, in the Tri-Border area with Paraguay and Brazil. A new fixed military presence in this area has been mooted since the George W. Bush administration, justified by then Secretary of State John D. Negroponte by the supposed threat of “Hezbollah cells” in the region. A decade ago, with Argentina off-limits under the Kirchners, the now civilian deputy commander at Southcom, 2013-17 Ambassador to Brazil Liliana Ayalde, pressured then Paraguayan president Fernando Lugo to allow expansion of US military presence there, a suggestion that according to Ayalde herself, made Lugo recoil in his chair. Lugo was removed by a procedural coup in 2012, and replaced by his conservative vice from his main coalition partner, very much like the fate that befell Dilma Rousseff four years later.

With Brazil’s 2018 elections looming, of the main candidates, only PDT’s Ciro Gomes, the triple PT/PCdoB ticket of Lula/Haddad/Manuela and PSOL’s Guilherme Boulos are offering anything significantly different to Macri’s withering Wall Street-friendly Neoliberal example. As Argentina’s economy enters a far worse crisis than anything Brazil has seen since the era of Menem and Cardoso, it is perhaps a sobering moment for those promoting the continuation of Temer’s extreme Neoliberal programme. This time they hoped it would be implemented with an elected mandate, just like Macri achieved, albeit with little help from vulture capitalist Paul Singer, who banked $2.4bn profit as a result.

[qpp]