Brasil today sits at a rare turning point for any country. Despite the furore surrounding the Petrobras scandal and the water crisis in São Paulo there are far more pressing issues that underpin whether Brasil can make the very difficult jump from middle income to rich, emerging to developed country, in the near future.

Brasil did not fall out of the sky fully formed the day before I arrived, getting a grip on how far Brasil has come in the past 20 years, especially in the last 12 requires a deep understanding of Brasil’s longer history. On Brasil Wire I previously looked at Brasil’s maturing stage of economic development with explanations to why goods in the the country often seem expensive and poor quality compared to a fully developed country. In this article I will take a broader view of Brazilian politics in general and start to pick apart some myths to give readers a contextual understanding of Brasil’s current stage of social development.

To understand why Brasil looks the way it does today requires looking backwards. It is very easy to glibly blame “Brazilians”, however the reality is that a vast majority of Brazilians are the victims of the country’s problems not the perpetrators. The nature of the power structures that have formed over the centuries in Brasil means that more often than not the kind of people in positions of power are exactly the ones you don’t want anywhere near them – sound familiar? For all of the poverty pornography of favela journalism, tales of corruption and crime, Brasil is a remarkably unremarkable country. One of my twitter followers once dryly responded to one of my tweets questioning yet another favela story in the British press with “I guess ‘Brazilian sits in traffic for two hours on the way to work’ doesn’t make good copy”.

It is also important to remember Brasil is a massive, diverse and – often ignored – Federal Republic. What happens in Rio de Janeiro in terms of security, public services and the up coming 2016 Olympics is the Rio state government’s responsibility. Far too often foreign journalists use “Brazil” to describe what are local issues that the Federal government and President Rousseff are constitutionally barred from interfering with. One of the most endearing “guides” to Brasil was written by Juan Pablo Villalobos for Granta magazine, This single paragraph is really all anyone needs to know about Brazilian diversity.

Identity crisis (1). São Paulo and Manaus are as similar as Wales and China. Comparing Rio de Janeiro and Palmas is like comparing a shoe with a rocket. Porto Alegre and Rio Branco like a frog to a cup of coffee. Belo Horizonte and Salvador like a human hair to a constellation. The sum of these differences is called Brazil.

On first impression it would be easy to wonder why Brasil often looks so shabby, with broken pavements, run down public buildings and poorly maintained public spaces. This is especially apparent when you see the flip side; sparkling shopping malls, new cars everywhere and tower after tower of new apartments going up, often it can look as if the country is one big building site. Much of this is selection bias we barely notice. Get out of the any main tourist city in Europe’s southern countries and things start to look remarkably similar to urban centres in Brasil. But this is case almost everywhere. I spend a lot of time in the United States, not in nice neighbourhoods in tourist areas. I see run down, badly maintained streets, pot holes and trash on the street. We all curate our lives, how many of us ever visit the Banlieues when in Paris, the slums that circle Madrid & Naples or the sink estates in Scotland and Northern England? Even Brazilians on their holidays only see the rosy side of Europe and the US. Brasil definitely does not have a monopoly on urban decay.

Many of the daily annoyances in services come down to Brasil being a victim of its own success over the past 20 years. Reports from various organisations including the OECD have shown for years Brasil has struggled with a skilled labour storage as it’s economy normalised in the 2000s. Decades of non-investment in education mean that today large volumes of positions in Brasil are taken up by people that had few educational opportunities growing up. Brasil has shortages across the entire economy from plumbers to oil and gas engineers. To be honest it is a testament to Brazilian ingenuity and flexibility that the country has managed to pull itself out of the gutter in such a short time frame with so few highly educated people, 2012 figures showed that only 11% of Brazilians had graduated university. I want to be clear here, Brazilians cannot be blamed for their past lack of opportunities in formal education. Brasil’s past leaders criminally failed their responsibility to their countrymen and women. Brasil today is playing a constant game of catchup across the board, with problems compounded by a sudden surge in a consumer class that never used to exist.

Brasil is a country with 500 years of deeply troubled history; colonialism, slavery, horrific exploitation during the Mercantilist period, then dictatorship, firstly the arguably positive Vargas period, then brief democracy followed by the ineptitude of the Military era from 1964 to 1985. What followed in the first 10 years of democracy was effectively a lost decade as dictatorship power structures jostled for domination. Economic crisis after crisis finally focusing minds with the initiation of the Plano Real under President Itamar Franco.

I briefly want to interrupt this short 20th Century political history to explain why the 1964-85 dictatorship was so damaging to Brasil and why there is often subconscious – and occasionally overt – nostalgia for Military rule amongst some of the upper and middle classes:

During 1964-85 Brasil was effectively ruled exclusively for around the top 10% of the country’s income bracket. Brasil functioned on a class and racial caste-like system that perpetuated grotesque levels of social and economic inequality that are very hard to fathom today. A small group benefited from the country’s wealth while dictatorship maintained a vast reserve labour army. Brief attempts to modernise the country firstly under dictator then democratically elected President Getúlio Vargas then by Juscelino Kubitschek and finally João Goulart resulted in the forces of reaction mobilising a coup against the democratic state in 1964, backed by US President Lyndon B. Johnson. Released tapes of the discussing the coup and US support between Johnson and with Undersecretary of State George Ball and Assistant Secretary for Latin America, Thomas Mann make for chilling listening.

You will often hear older Brazilians mentioning learning Latin and having Ballet classes in public school in the 1960s and 1970s – these were often run by the Catholic Church. The problem here is that it was very easy to have high standards when a tiny proportion of the population attended any kind of formal education. The living standards of Brasil’s middle class and wealthy was massively subsidised by the extremely low cost of service work during the dictatorship. This note in the 1971 Brazilian Portuguese reader Crônicas Brasileiras is telling:

Wages of workers were repressed, unions were heavily restricted, with widespread suppression of any struggle for better working conditions. Recently the evidence of collaboration between foreign carmakers and Brasil’s military rulers has come in to light in Brasil Truth Commission findings. Corruption and collusion between foreign automakers and the military regime even made it into Brasil’s 1965 film São Paulo, Sociedade Anônima with an Italian parts maker’s bribery and shoddy manufacturing setting the backdrop to the story -this is a very good film and well worth watching.

It is easy to underestimate the corrosive effect dictatorship has on a society and a culture. With over twenty years without recourse to democracy, those that are mostly likely to thrive under dictators are the corrupt and bullies; nepotism and clientelism replace civil society, and meritocracy collapses. Many of Brasil’s wealthy never had to face any real meritocratic competition with their follow citizens. Their massively subsidised lifestyles meant they could buy their way out of State failure with private schools, health plans, they could buy security with militarised apartment blocks and buy “public” space at private clubs. State workers were also rewarded with layers of compulsory non-government organisations like SESC (Social Service of Commerce in English) that provide what would normally be public services via a payroll tax – I should say here this is not a criticism of organisations like SESC, which provide Brasil with some of it best public spaces and access to culture. Sharply rising incomes of Brasil’s poorest has cut into middle class purchasing power, few now but the rich can afford live in maids.

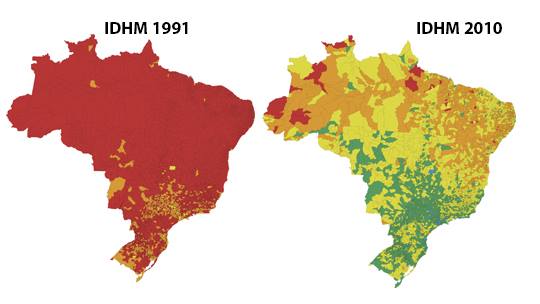

Unfortunately this toxic sense of entitlement seeps into Brasil’s opposition politics, meaning genuine debate about the future of the country is shrouded in outdated Cold War paranoia. Instead of providing a vision for the future of Brasil many people like the small groups protesting for President Rousseff’s impeachment are actually wanting the Brasil of the past. Leading Brazilian economist and architect of many of Brasil’s poverty busting programs Ricardo Paes de Barros outlined just how critical the situation was during and after the dictatorship in a recent interview in Brazilian financial journal Valor. For those readers that think Brasil today is “bad” think about what Paes de Barros says in the follow quote “In 2000, Brazil had 50% of municipalities with HDI [Human Development Index] below 0.5, the average of Africa. Today, only 0.5% of the municipalities have HDI below 0.5. That is a stunning change in the country” Brazilian journalist Mauricio Savarese expands on this an an excellent article New Brazil HDI shows how much the dictatorship hurt the country.

While much of the global north was going through a prolonged period of social democracy Brasil was condemned to the reenforcement of antiquated social structures that had plagued the country since the colonial/slavery period. Most of Brasil’s contemporary problems is the friction between 19th century class structures and a leftwing nationalist desire for the country’s potential to benefit the population as a whole – unlike in many Western countries it is the left in Brasil that are often the most nationalist. I would also say that for those of us coming from Anglo Saxon countries are in little position to lecture Brazilians on how best to improve their country. We – those in the English speaking world – are sleepwalking back into the kind of inequality that plagues much of Latin America today. Lecturing the Brazilian government and people that they should follow our failed policies of weak worker rights, minimal financial regulation, while privatising further already tenuous public goods has resulted in inequality in the English speaking world fast approaching pre World War I levels. It is also important to remember the the wave of left-wing governments that swept Latin America for the last 15 years was a direct reaction to failed Washington Consensus policies, forced upon populations, that valued ideological purity over human lives. The results have not always been positive certain governments rapidly descended into using class war to stay in power. However, I believe the model that in particular Brasil has followed, going straight for the low hanging fruit, has without a doubt resulted in nothing short of a miracle if we look at the country only 20 years ago, with little of the toxic social tension we see in some of Brasil’s neighbours.

That said, it has been clear for a number of years now that new ideas and vision are needed. As I said in the opening paragraph, Brasil is at a crossroads, the kind of Big Vision of the 1995-2003 Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC) and then 2003-2011 Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) administrations is needed again. Unfortunately for current President Dilma Rousseff has been left with the a lot of the mess carried over from both former Presidents that was swept under the carpet, to put it in pithy topical metaphor, she has been paying for her predecessors’ mistakes 10 x com Juros.

The perceived polarisation that now exists is more about how each party was ground down by the realities of Brazil’s oligarchy and their own particular internal dynamics, especially that of the competing egos of Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Todays polarisation belies the party’s close ties and common roots. Lula was an early supporter of FHC’s political career in São Paulo, and in the past they would have been regarded as good friends and allies. The real story of the past 20 years however, has been the massive concessions and compromises made by progressive forces in Brasil to create a more equal society, even to the point of becoming the thing they hated. This is most clear in both FHC and Lula’s respective parties, the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) and The Workers’ Party (PT) governments over the past two decades. Both are broadly similar ideologically, with the PSDB initially formed by Brazil’s left-wing urban elite and the PT from a coalition of trade unionists, artists and progressive Catholics – amongst others – both parties have large groups of former dissidents and during the first years of democracy, were likely partners for Presidential races.

Too often though, there is an underlining narrative that somehow Brasil has been in decline after a period of Milk & Honey during the administration of Fernando Henrique Cardoso from 1995-2003. In my opinion FHC’s government needs to be looked at as two very distinct periods; the first coming out of the government of Itamar Franco and the successful Plano Real that stabilised the Brazilian economic after decades of mismanagement firstly by the military dictators and then the civilian governments of José Sarney and Fernando Collor de Mello. Cardoso is frequently credited as the key instigator of the the plan, but was in fact the public face of a large team of economists and academics. Financial Times former São Paulo correspondent Jonathan Wheatley, frequently and rightly points out that taming inflation under the Plano Real did a lot of the ground work for stabilising the lives of Brasil’s poorest citizens. But the negatives of this early stage of stabilisation meant that with little money to spend, investment in education and health was nearly impossible. FHC’s mandates did not turn Brasil into a New Jerusalem, nor was he the Philosopher King now presented by sections of Brasil’s media. His mandates were just as plagued with allegations of background – possibility illegal – deals, vote buying and corruption as any period in Brasil. The main difference is a revisionist media that seem to want to rewrite history in his favour. This was compounded by Federal Police that seemed loath to do anything to fight against Brasil’s near total impunity for political corruption post dictatorship until 2003. As discussed in a previous Brasil Wire article Brasil’s Citizen Kanes major Federal Police operations against corruption rose from a few dozen in 2003 to nearly 300 in 2012, it is doubtful that had anything to do with increased wrongdoing.

In 1997 FHC had Brasil’s constitution changed to allow a second term – something often viewed disparagingly by Latin America commentators today. However FHC’s second mandate was a disaster – currency crisis, a de-linking of the Real to the Dollar that resulted in an explosion of foreign debt and an IMF bailout, unemployment spiked and average annual inflation still remained stubbornly high in double figures – twice what today is called “high inflation”. I certainly think that at the time FHC was – in his first term – the ideal figure to lead the country out of decades of chaos, but much as we are seeing now, the reality of holding political office in Brasil means dirty deals and compromises were necessary. FHC’s legacy is rightly held up as a turning point in Brazilian modern history, but equally Brasil was extremely lucky to have what came next. I could write another 2,000 – 200,000? – words just on the two mandates of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, but it would be difficult to improve on Tom Hennigan’s tour de force Slaying the Octopus – the final section on the Workers’ Party administrations summarises most of what needs to be said about the compromise and moral descent of the party during 12 years of governance in the face of Brasil’s power dynamic.

Regardless of the underlying problems and equally compromised mandates of Lula, the transition from one FHC to Lula next was unprecedented. For all of Lula and his party’s many faults they continued with a policy of steady economic management and used the financial dividend to clear Brasil’s international debt and begin the largest expansion of public services and poverty eradication in the country’s history. The cry from the Workers’ Party detractors here is always “but they just copied the polices of the previous administration”; that may be so, but any student of public policy knows that not changing a policy is as much a decision as changing one. As I opened, Brasil today is at crossroads, the forces of reaction are once again knocking at the door.

The greatest opportunity for Brasil now is not repeating failed reforms of the Post Reagan-Thatcher era, but fighting an internal political and power structure that has been shown far too much compromise over the past 20 years.