Brasil has a healthy and noisy media landscape; from sophisticated daily papers and weekly magazines comparable to any in Europe, right through to trashy supermarket rags like you see across the United States. But at the top level there is a deep undercurrent of conservatism that often goes unnoticed, a conservatism that pre-dates any of the current party-political brands, and a conservatism that encouraged & supported the military dictatorship. A handful of families dominate ownership of almost all mainstream media, for example, Marinho (Globo), Mesquita (O Estado de São Paulo), Frias (Folha de São Paulo), and Civita (Abril, publishers of the leading weekly, Veja).

Like in most countries, Brazilian media fall into categories of the good, bad and ugly, but what is different is how certain media organisations developed their current market positions. To be clear, amongst the agenda-setting media there is only one minor weekly publication that you could describe as supportive of the current governing PT/Workers’ Party, overwhelmingly Brasil’s serious media are in either overt or implied opposition.

This does not mean that all are of the same ilk, there is nuance and constructive criticism, especially amongst the daily newspapers. But there are also concerted, poisonous and deliberate attempts to undermine Brasil’s democratic institutions.

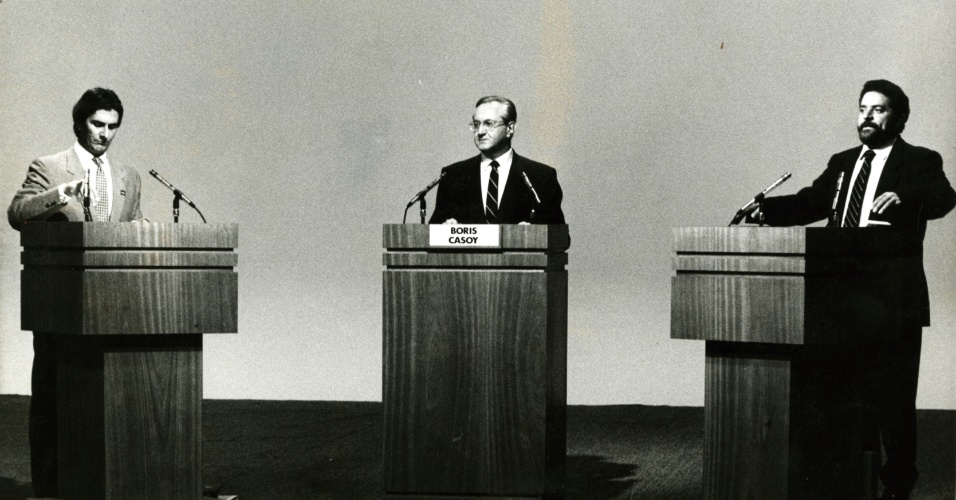

The most notable instance of this was when Globo Network, Brasil’s largest and most powerful private media organisation, during the 1989 Presidential election, broadcast edited versions of live television debates deliberately to favour its preferred candidate Fernando Collor de Mello (whose presidency ended in disgrace after impeachment for massive corruption).

The 1993 British documentary ‘Beyond Citizen Kane’ chronicles Globo Network’s rise during the dictatorship. Watch it in full here.

Tellingly Globo has repeatedly tried to block and censor the broadcast of the documentary, including in the United Kingdom. To date the program has never been publicly broadcast in Brasil, and private broadcasts have been subject to censure, in 1994 a public showing of the film Modern Art Museum in Rio de Janeiro was raided by the Military Police, in 1995 Globo even attempted to have a copy of the film removed from a public university in São Paulo.

Reporters Without Borders recently produced a report on Brasil’s media landscape entitled Brazil, the Country of 30 Berlusconis which makes for chilling reading. Brasil’s media laws have seen little reform since the military rule from 1964-85, and any attempt to reform laws to break up monolithic family owned media groups has been met with cries of “censorship” from the industry. Many politicians are either amongst the owners -Fernando Collor de Mello for example has major media interests in his home state of Alagoas- or are too scared of the potential repercussions at election time.

Elsewhere, Veja, the flagship title of Grupo Abril, and Brasil’s most popular magazine, is probably the most extreme in terms of its positional hostility to PT, and the left as a whole. A reasonable analogy with Veja would be the UK’s Daily Mail, and they are central to the propagation of a false narrative that the PT are “the party of corruption”. Thus corruption is used euphemistically to attack the Workers Party, as it has been against parties of the left around the world since the paradigm began. Considering the power of these networks & publishers it is very surprising that the PT enjoyed the electoral success they have had.

It is important to take into account that not all opposition to the Workers’ Party is simply destructive reactionary attitudes by media barons, the landscape becomes more complex at the upper end of Brasil’s media. Daily papers like Folha de São Paulo and O Estado de S. Paulo despite having editorial positions against the PT Government often provide a constructive opposition that is sadly lacking in political parties like PSDB. Both papers have explicit editorial positions and Folha publishes a “What We Stand For” section that reads like a progressive political party manifesto. Yet despite this, Folha in particular struggles to offer a balanced picture of Brasil’s political parties. Estadão to it’s credit will openly admit a preference in candidate, Folha’s problem is it declares neutrality when the reality is far from it. Folha clearly has a large number of genuinely progressive editorial staff and journalists. Special Reporter Fernando Canzian’s film report on 10 Years of Bolsa Família was emotional and showed genuine concern and support for a program that has pulled millions out of poverty, yet despite this his columns exclusively focus on opposition to PT.

Veteran columnist Xico Sá left Folha during the 2nd round campaign, after a piece expressing support for Dilma Rousseff was refused for publication. Meanwhile, new information involving a Petrobras corruption scandal has been leaked for maximum damage to Dilma’s chances, despite her not being personally implicated.

Sometimes it seems Brasil’s media want a progressive and socially inclusive Brasil, they just don’t want the Workers’ Party to be the ones delivering it. It is given much higher scrutiny and held to much higher standards than the country’s other parties, after all, it is in office. However to focus solely on one party, and often turning a blind eye or selectively reporting wrongdoing by other parties diverts attention from corrupt officials and creates a toxic environment that labels one political party as uniquely responsible.

One of the most recent examples of this was the discovery of massive corruption in São Paulo’s administration of INSS taxes under the previous administration of Gilberto Kassab. The problem wasn’t reporting the corruption, it was how quickly it was diverted to a story implicating the Workers’ Party who were neither in power at the time, nor was the current major Fernando Haddad implicated, yet a single PT member from a previous administration was. Instantly the headline became Corruption at the Heart of Haddad administration, wilfully ignoring that this occurred when Mr Haddad wasn’t even in office.

Latest reports from the non partisan Movement to Combat Electoral Corruption show the PT to be 9th out of 14 based on party members under investigation. Considering the heavy scrutiny the Workers’ Party are constantly under it would be doubtful they were managing to sweep corruption under carpet as it was in the past. In fact the combating of corruption significantly rose during the Workers’ Party’s years in power.

The Mensalão case is the most pervasive example of bias and even more important because the narrative has also permeated into foreign media who almost never question the view presented domestically. It needs to be said that there is no denial that what politicians and private citizens were accused of, prosecuted and jailed for, happened. The real problem is misinformation in that is presented as exclusively a Workers’ Party case. The reality is that of the PT members accused in the scandal, a minority, none of them were accused or guilty of stealing public money for their personal gain – all were guilty of channeling money to other political parties in exchange for votes on key reform legislation from the first term of the Lula da Silva administration.

What is rarely mentioned is that the scheme was initially constructed by Brazilian Social Democratic Party members (PSDB) and affiliates in the state of Mina Gerais during the administration of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Both scandals are directly connected by businessman Marcos Valério who was eventually sentenced to nearly 30 years in jail for his part in the scheme that had seeped into the Workers’ Party coalition. It is important to understand that most of the guilty parties involved in the case were not Workers’ Party members but politicians from the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), Progressive Party (PP) and Brazilian Labour Party (PTB), all of whom received monthly payments in exchange for votes. This type of scheme is age old in politics, not only in Brasil, but PT had been elected on a wave of “new politics” similar to the aura that surrounded this year’s candidate, Marina Silva.

No Workers’ Party member was accused of enriching themselves, but facilitating the enrichment of others. Normally this is called blackmail, not bribery. The damage the case has done to the party has still not been repaired, it offers constant ammunition to a hostile media, but beyond that it shattered trust in a party that promised to do things differently.

The greatest crime of the Mensalão was not the money involved but the undermining and weakening of Brasil’s democratic institutions, something for which all the parties & individuals involved, not only the PT, need to be held accountable.

The media’s selective indignation over cases of corruption is an insult to all Brazilians who want to see an end to it.

[qpp]