The vast beach at Regencia was virtually abandoned. Instead of the usual tourists to one of the most important nature reserves along the Espirito Santo coast, a few desperate and sad groups were working the sand. One was a flock of vultures, which was attacking the fish carcasses that were constantly washing ashore. Another was Tamar Project volunteers, who were working fiercely to mark out leatherback turtle nests for egg collection, for if any of this endangered species’ juveniles emerged from their burrows, they’d meet a swift death in the toxic, red ocean.

The story of the Samarco dam collapse has evolved since its mud first exploded down the mountainside next to the town of Mariana, Minas Gerais state, two weeks ago. We should never forget while covering this slow moving atrocity that people died there. Many are still missing. A whole town of people lost their homes and businesses in an instant. But move the story has, as the toxic iron ore waste from the dams has made its way along the 500-kilometre Rio Doce.

Last weekend, it reached Colatina, a city that lives and survives by the river. Most of the 150,000 or so residents of that city now have no clean drinking water. And now, the mud has reached the ocean at the mouth of the Rio Doce, next to the town of Regencia. Being only a three-hour drive from where I stay in Brazil, I had to see it with my own eyes. I had to touch this polluted water that has caused so much damage as it’s edged downstream.

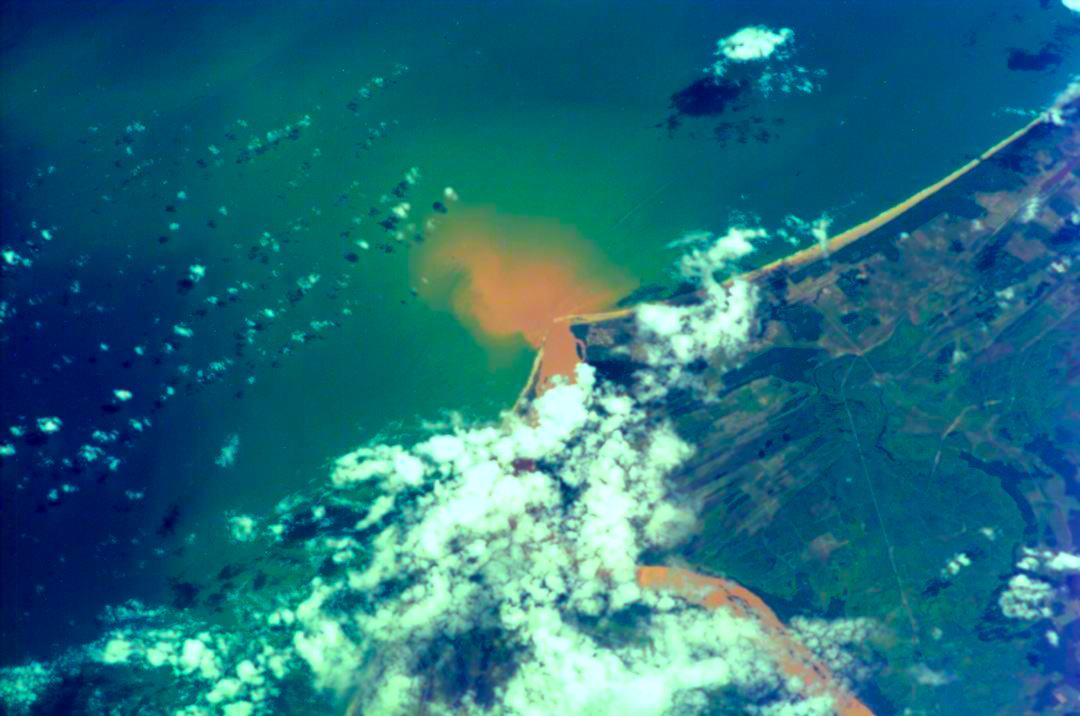

At first, I imagined the sea would disperse this dirty water quickly. Vale, BHP Billiton and Samarco – take your pick of the three companies involved in this saga as to who’s really at fault – obviously thought the same. Diggers hired by them are working the main channel to the sea in the hope of draining the water to the ocean quicker. But for what I can see, the brown water has accumulated along an enormous patch of ocean, hugging the coast. The tides here move laterally along the beach. It’s in seeing this huge patch that you understand the immense scale of the pollution – and it’s barely even started yet, because most of the muddy water is still upstream.

I now agree with experts who say this water will affect the water from the river mouth, all the way to Espirito Santo’s capital City of Vitoria and beyond. This is enormous, not because it will disrupt bathers who enjoy the gorgeous beaches along this path, but because thousands of fishing communities who live along this coast will be devastated. The mud continued killing once it reached the ocean, and I have no doubt it will continue to do so as it moves down the coast. The turtle hatchlings on the beach may be able to be saved by the Tamar Project workers, but the fish do not stand a chance. If the river has been declared 100% dead (all the fish, of which some were unique to the river, have been killed), then what about those in the ocean?

People who live in Espirito Santo state are known as ‘Capixabas’ – or ‘from the sea’. This has strong connotations to the fish and seafood that is naturally abundant in the area. Perhaps, in future, this name will have to be changed. Meanwhile, a huge proportion of the Samarco mud lays up high on the banks of the Rio Doce. One must wonder, when it rains, will this tragedy continue repeating itself in slow motion as all the mud works its way out to the Atlantic ocean?

Shaun Alexander is a journalist and filmmaker. His photos of the tragedy are on instagram and you can subscribe to his YouTube Channel here.