By Andrew Cumming.

Rio has Baile funk, Salvador has Axé, Belem and the Amazon have Brega, but what does the vast interior of Brazil have? That huge expanse of outback that takes in the states of Goias, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, and Minas Gerais? It has Sertanejo, which is basically Brazil’s own Country and Western genre sung in Portuguese by cowboy hat wearing, big buckle bearing raconteurs, a species normally found in duos.

Wander the interior of the country and you soon hear that this music is ubiquitous, of course the kids drive around and listen to those fantastically minimal ostentatious funk tunes, whose main purpose seems to be to rankle parents (which definitely works!), but tune in the radio, go to any bar or restaurant and Sertanejo is the music you hear.

This dominance of the music is quite hard to bear, but, I thought, that there must a more interesting side to this genre. Dig deep and classic music can be found, do some research and you can see that people are working with the genre and doing something interesting with it.

Sertanejo or Musica Serteneja (from sertão, the outback) originates from Musica Caipira, basically hillbilly or roots music, it was originally popular with rural residents and urban working-class labourers in São Paulo and Minas Gerais areas, but its popularity expanded immensely in the eighties when Chitãozinho and Xororó took the electrified sound of Nashville and the mega shows of Garth Brooks and Billy Ray Cyrus and popularised Sertanejo throughout São Paulo and the interior states. From hereon Sertanejo sold vast amounts and the record companies basically pushed all their other artists aside to focus on this music.

It started to dominate culturally during the early nineties, namely the “Collor Years” (disgraced and impeached former President). It soundtracked the middle classes and the political parties in Brasilia, there is an emblematic photo of then president Collor and his first lady Rosane surrounded by sixty sertanejo duos in the Collor family mansion (he was never one to do things by halves!). Renowned Brazilian music chronicler Nelson Motta wrote in his memoir “Tropical Nights” how the record companies panicked at the end of the nineties and devoted all their budgets to recording sertanejo, as it was assured of low overheads and quick sales. In fact the genre overshadowed Motta’s beloved MPB, and he went on to describe it as “a naïve and melancholic music of the prosperous interior, as São Paulo, Minas and Goiás urbanize, electrify, fly in jets and sell millions of albums”.

The music basically followed this formula of sub-Garth Brooks country pop until the late noughties when a new generation came in with an even more pop version. Having grown up on the various regional pop musics of Brazil, these new singers incorporated Pop, Funk, Axé, Samba and Pagode to create Sertenejo Universitario, an extremely popular hybrid. However, Sertenejo Universitario innovates in the same way pop innovates, it absorbs new sounds and production techniques to sound relevant, but it’s not innovative in the same way the underground is. It merely takes established sounds and rhythms and recontextualizes them in an effort to sound fresh (and above all marketable).

But rural music has an impressive story, a history dating back to 1910 of troubadours and cowpokes telling stories through song, of homemade guitars, invented tunings, and of idiosyncratic characters. It is a music that comes from Portuguese folk traditions, characterized by singing in parallel thirds and sixths, it draws from the song form of the Luso-Brazilian heritage known as moda de viola. It is also a merging of the rural country sounds of south-central Brazil with the vocal and instrumental traditions from northeastern country music, more specifically from Pernambuco.

Classic tunes and standards were already being recorded in the 1920s, difficult to say who actually invented the genre but João Pacífico is considered by many to be a true originator, specifically with the hit “Cabocla Tereza”. Cornélio Pires could be considered the Alan Lomax of caipira culture, being the first to put the music to wax and present it to a wider world. Raul Torres’s compositions are considered early classics of the genre, listen to the weeping slide guitar on “Moda da Mula Preta” recorded with Florencio in 1945 and understand why. Tonico & Tinoco are also essential when discussing the early years, as they are considered the most active duo in traditional caipira music, with over 700 recordings uninterrupted since 1938.

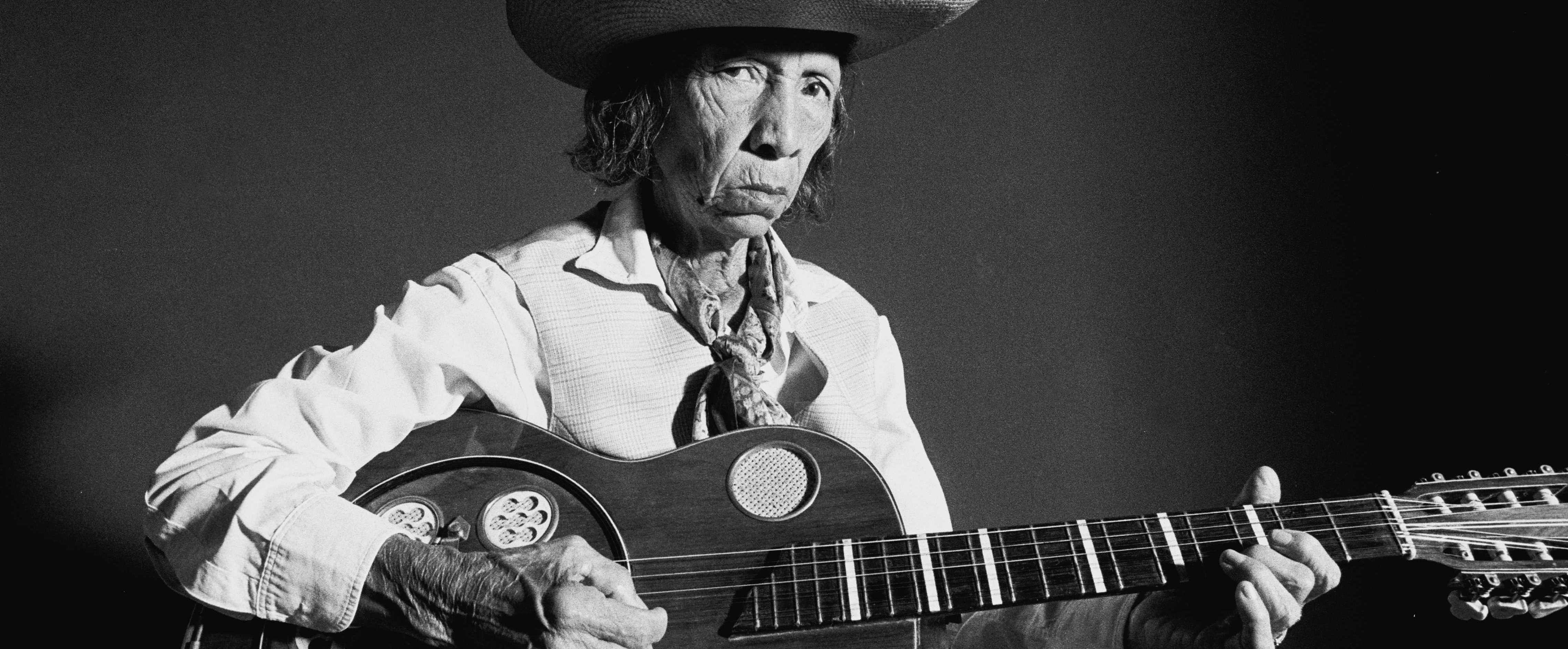

Start looking for intriguing and noteworthy music in the caipira genre and you soon come across the name Helena Meirelles. Probably one the most famous violeras in recent times, she led an incredible life full of high drama. Born in 1938 in Campo Grande in Mato Grosso de Sul state, she learnt to play by watching her grandfather and uncles playing and by the age of 9 was a natural with the instrument.

She was married off at 17, with a husband who wouldn’t let her play or sing. She soon ran off with a Paraguayan guitar player, she left him and her children to adoptive parents to play in whorehouses and bars of ill-repute. Comfortable in these environments, she would play for free. In a bizarre twist of fate she was included in a list from Guitar Player magazine of the 100 best guitar players in the world, a remarkable fact in that she was completely unknown at the time and a demo CD had ended up in the editor’s hands. Of course after international recognition Brazil became curious and she was celebrated as the true talent that she was, playing in a formal theatre for the first time in her life at 67. Listen to her albums and you can hear why, a raw and uncomplicated sound emerges, a lived in voice tells tales of backwoods life. Her unusual viola tuning can be put down to the fact that in the backwoods the viola caipira is tuned to the singers voice. Barely able to read and write throughout her life, I am reminded of a friend’s anecdote, when he went to see her play in the incongruous surroundings of a hotel bar in the middle of São Paulo city, after the show he asked her to sign a CD, she half wrote her name, gave up, and said “that’s enough, eh?”

Move away from the beaten track and start poking around the sixties and you can find the eponymous 1967 album by Quarteto Novo, this jazz and MPB album features heavy use of the viola caipira (the acoustic guitar used in Caipira music) by the Pernambuco multi-instrumentalist Heraldo do Monte who was part of Dick Farney’s jazz band in the fifties, and has an incredible line up of musicians including Hermeto Pascoal, Theo de Barros and Airto Moreira. The group was originally put together to back Geraldo Vandré, who in 1968 released the radically leftist and anti-dicatatorship classic “Canto Geral”. This album belts out its themes supporting the agrarian workers, and its message of the how power enables the rich to grow through poverty still resonates today.

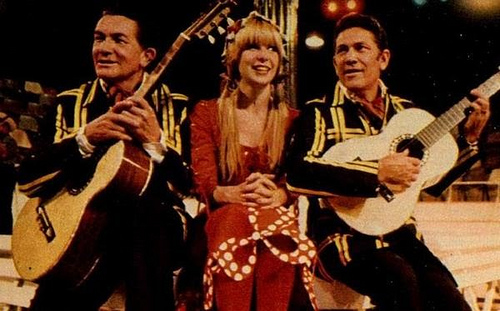

Os Mutantes, probably Brazil’s most famous psychedelic Tropicalistas, were partial to a bit of country music as well as their beloved Beatles. On their second eponymous album from 1969 the track “Dois mil e um” (2001), written by Rita Lee and Tom Zé, is clearly a homage to Sertanejo and plays with the genre with its brusque time changes and a freak out interlude which includes use of a theremin. Os Mutantes were arranged by Rogério Duprat, the main orchestral arranger behind Tropicalia, and generally considered to be the George Martin to Os Mutantes’ Beatles. The Caipira connection continues when in 1970 Rita Lee, still a Mutante but about to embark on her solo career, was involved in an onstage fashion showcase with a countryside theme. The musical directors of the show were Rogério Duprat and Júlio Medaglia, who for two months went into the interior of São Paulo to research songs and were struck by the unusual time signatures they heard. The result of this research and the showcase was the rarely heard Duprat album by Rogerio Duprat, Orquestra e Coro: “Nhô Look, as mais belas canções sertanejas”. It’s not a great work, being quite pedestrian in its approach but is of interest as Rita Lee can be quite clearly heard in the choir, and Duprat’s arrangements of these traditional tunes does let their charm shine through.

Rita Lee

In 1971 the genre was about to be completely shaken up and adopted into the psychedelic underground with the release of Lula Côrtes and Zé Ramalho’s masterpiece “Paêbirú: Caminho da Montanha do sol”. It is probably the rarest and thus most expensive Brazilian album of all time, fetching easily $5000 on discogs, the rarity is due to a storm that flooded the pressing plant destroying most of the original pressing. This event is tragic as this album could have been the successor to Tropicalia’s reign and herald the beginning of a unique Brazilian psychedelic country rock, it’s that good!

The album includes the cream of northeastern folk and psychedelia such as Alceu Valença and Geraldo Azevedo, and has the atmosphere of a freaky commune. Imagine, if you will, peak period, “In Search of Space”, Hawkwind but formed in the arid sertão of northeast Brazil rather than grimy 70s Notting Hill. Nonetheless, amongst the raga rock and afro-Brazilian mysticism, tracks like “Harpa das Ares” and “Beira Mar” ring and chime with Caipira guitar tunings, making this album certainly the freakiest entry into the oeuvre.

Somewhat stretching the limits of what could be considered experimental caipira is the long lost LP “Caracol” (1989) by programmer and guitarist R.H. Jackson and percussionist João de Bruçó. A challenging listen to put it mildly but its mixture of studio experimentation and traditional rhythms along with themes of the interior of the country draws you in. R.H. Jackson studied gamelan and cyclic music (guitar styles) and this can be heard in a twisted way in Caracol. Jackson lives on the border of São Paulo and Minas Gerais states in São Fancisco Xavier where he continues the roots tradition of making his own instruments based on caipira guitar tunings (open E known as cebolão and open G known as Rio Abaixo), the instruments are used in his latest project Bitz do Além (além meaning beyond, both the frontier of SP/MG and normal caipira music).

The guitars of R.H. Jackson

An album that really opened my ears to Musica Caipira was the wonderful “Violas de Bronze” by Siba and Roberto Correa. Again from Minas Gerais, Roberto Correa is an interesting case of an academic devoted to the “viola caipira” and is renowned as a composer and researcher. But the album Violas de Bronze doesn’t retread past classics, with Siba playing the northeastern instrument the rabeca, it contains original compositions that demonstrate tango and flamenco influences all guided by Correa’s viola and Sibas sawing, almost grating, rabeca. Opening track “Cara de Bronze” had one reviewer going so far as to describe it as Robert Johnson meets Helena Meirelles.

Siba & Roberto Correa

There’s something in the water in Minas Gerais, the stunning, sprawling rural state, as Zé Rolê aka Psilosamples from Pousa Alegre makes what has been described as electronic bush music. It’s electronic music sharply edited and cut using regional sounds and rhythms. His first album, “Mental Surf” is clearly rural music fragmented, sampled and edited from a tiny bedroom studio. Listen to a track like “Estrada de Terra” and you can hear the viola caipira being reconfigured and played around with. Although a clear product of the internet, in an interview with the site musicnonstop, Psilosamples talks of channelling the countryside in his music, though it’s not an overriding concept for him, being isolated in the country or in São Paulo city is creatively stimulating either way.

Psilosamples

Finally, investigating my own region, I see a scrappy pair setting up outside the local theatre. Known for their guerrilla tactics in putting on shows wherever there’s a crowd, Que Miras Chicón describe themselves as a mix of Tião Carreiro, Caju & Castanha and The White Stripes. This rough n’ ready duo of drums and acoustic guitar celebrate and revel in the rural life, even in the title of a song like “Eita Muié” (hey woman) they use the phonetic pronunciation of the rural accent from the interior, a source of amusement for the more urbane. But they are one of the few people I know of who celebrate this culture and take a DIY and, cliché ahoy, punk attitude to it. I asked them whether where they come from relates to the music they play and I get a direct answer, “We were born and raised in Monte Azul Paulista (interior of São Paulo), but nothing is contrived, we just like caipira music and punk!”

Que Miras Chicón are not dissimilar to groups like Motormama, Mercado de Peixe and Charme Chulo, groups that take an indie aesthetic to rural music, they also cite Olendário Chucrobillyman as a contemporary, his one man band vibe certainly fits, but he comes from an American blues tradition, while the others are more clearly influenced by Brazilian roots music.

Other groups like Brasil Matuto Ensemble and Matuto Moderno (matuto means someone who lives in the bush) take the tradition of roots music and further their research, adding rock leanings, or orchestration and improvisation.

Caipira music has come a long way from the backwoods, it easily fills stadiums now, but as with any big selling genre, scratch beneath the surface and there’s a lot that will surprise and challenge you.

Brazilian Caipira Roots, a playlist by andyalastairc on Spotify.

Article published in its original form at Perfect Sound Forever.

[qpp]