A surge in abstentions has prompted the Brazilian Electoral Court to act on long voting lines that blighted the first round of the presidential election. Although he won comfortably, voting data suggests Lula vote was most hit by the unexpected no shows, which also skewed polling accuracy.

At the October 2 first round of the presidential election, Lula da Silva picked up 26 million more votes than the Workers Party candidate Fernando Haddad did in the 2018 first round, and bettered his 2006 highest tally by 10 million votes, near equaling the % vote share. The former president fell just 1.57% of taking the presidency, in an agonising night for supporters.

Abstentions were the highest since 1998. That was last time a presidential candidate won outright in the first round.

Lack of understanding of the runoff system, and media coverage of Bolsonaro’s higher than expected percentage of the valid vote count, added to an impression that frontrunner Lula had performed more poorly than expected, or even lost the first round.

With the powerful General Braga Netto having replaced General Mourão as his vice candidate, Bolsonaro’s military-dominated government has famously made repeated public attacks on the democratic system. Among these were a demand to independently audit the vote, for there to be a printed record of all votes, and explicit threats that the far-right president would not recognize the election result should he lose.

Debate over the security of Brazil’s electoral system has focused on the electronic voting machines. In its defense of the system, Brazil’s progressive forces may have fallen into a trap in discounting possible malfeasance using age-old, unsophisticated–but no less effective–methods.

This has prompted democratic forces to double down in their defense of the electoral system, and in particular the voting machines, despite the military contracting a Mossad-linked Israeli firm to investigate vulnerabilities, under a premise of “safeguarding” the election.

But warnings prior to election day and on the ground during the vote show that other strategies may have been at play. New research by polling agency Quaest shows that asymmetrical abstentions harmed Lula’s vote and likely prevented a predicted first round outright victory.

Unexpected surge in abstentions

Quaest projects that of a 21% total abstentions, Bolsonaro voters accounted for 32%, while Lula voters were responsible for 45%. Without this asymmetric abstention, Lula would indeed have taken the presidency in the first round.

Researchers have sought to analyze voting data and try to ascertain what lay behind the surge in no shows, why it as asymmetric, and where it was most evident.

Abstention affecting Lula’s support base is not new. Traditionally, lower-income abstention is greater. Distance to polling stations and obligation to work on election day all affect the voter segment in which Lula is strongest. Right-wing lawmakers’ efforts to end free election day transport in cities such as Porto Alegre caused anger prior to the vote.

Regardless, some of the findings have been disturbing. In northeastern Lula stronghold of Recife, where the Workers Party candidate gained 3,558,322 votes, 65,27% of total, voters complained lines up to 4 hours cast their votes, and several polling station addresses were changed at the last minute. While many observed Brazil’s normal rapid voting process, stories of unprecedentedly long voting lines and abandoned attempts to vote, were circulating nationwide on election day, sparking early fears that something was wrong compared to previous elections.

Lines of up to 3 hours were reported around the country by Folha. In particular São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Brazil’s most populous state, São Paulo produced some surprising election results for both Governor and Senate, and Bolsonaro beat Lula by a higher margin than predicted.

A new, optional biometric registration system was initially blamed for the delays at polling stations, but Superior Electoral Court president Alexandre de Moraes denied that this was responsible. Many voters also complained that machines not functioning correctly.

Anecdotal reports talk of voters leaving for lunch and returning only to find even longer lines. Many simply went home rather than wait.

The conventional interpretation of the first round election results is that Lula got the near 50% that the polls had predicted, while Bolsonaro had an unpredicted surge, beating the projections of pollsters by around 7 points.

However, as Political Scientist Antonio Lavareda has noted, these data can be looked at a different way, with a focus on abstentions. Let’s have a look at the pre-election polls.

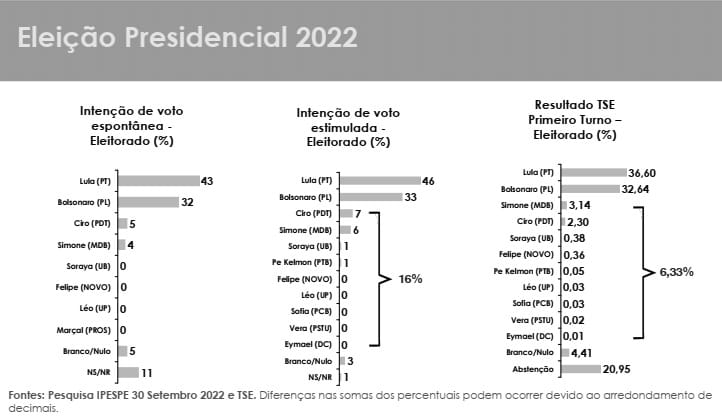

In polls from three days before the election by IPESE–which were in line with other polls at the time– Bolsonaro was polling at 32% in spontaneous polling (where respondents had to come up with the names of the candidates) and 33%, when candidate names were offered. This is far below Bolsonaro’s total of valid votes on the October 2ndelection, in which he received 43.3%.

However, that 43% represents only what Brazilian election law calls Valid Votes, they do not factor in abstention, or null votes. If we look, instead, at the entire population that is eligible to vote in Brazil’s presidential election, the polls precisely predicted Bolsonaro’s count. 32.64% of eligible Brazilian voters selected Bolsonaro for president, exactly as the polls predicted they would.

It is in Lula’s vote total that abstentions seem to have made the difference. In the IPESPE poll, Lula was received 43% of spontaneous votes, and 46%, when people were given candidate names. However, 20.95% of eligible Brazilians did not cast a vote, and that abstention hit Lula especially hard, reducing his votes among the total number of eligible voters to 36.6%.

Whereas media coverage has talked of an upset, and Bolsonaro wave of support, This analysis of election data suggests that the incumbent was numerically where major polls had predicted. What changed however was that there was an unanticipated surge in abstentions, which disproportionately affected the vote of Lula da Silva.

This casts the long voting lines that have been reported, particularly in the Workers’ Party strongholds of Northeast Brazil and the peripheries of large metro areas in a different light.

The Mesários

Earlier in the election campaign, a push to recruit Bolsonaro-supporting volunteers to work as polling station officials, or mesários had caused alarm.

On September 25, it was reported that this had caught the eye of the TSE (Superior Electoral Court, which had found that “groups of bolsonaristas may have agreed to volunteer as poll workers”.

This election had seen a record number of volunteer registrations, going from 430 thousand in 2018 to 830 thousand, an increase of 93%. In all, 2 million people, 48% of which are volunteers.

In 121 Bolsonarista group conversations on the Telegram app that are being monitored by the University of Virginia in the United States, word “mesário” was mentioned only twice in January, In August it appeared 163 times. April and May, the month in which the voluntary registration of poll workers ended were the only previous times the word appeared in double digit numbers.

This led to fears that Steve Bannon-style tactics might come into play on election day, where the voting process is deliberately delayed, and abstentions generated through long lines. Such tactics were evident in the 2020 United States election, where Bannon had campaigned for Donald Trump supporters to register and train as voting officials to contest Biden votes. Trump refused to accept the result, like Bolsonaro has threatened to in Brazil.

Bannon casts a shadow over the imminent US midterm elections. Vanity fair writes that “Embracing the “precinct strategy” promoted by Steve Bannon, the GOP is reportedly preparing to sow chaos in the 2022 election by creating an “army” of poll workers and Republican lawyers to challenge voters in Democratic precincts.”

A year ago, Bannon “declared war” on Lula, calling him “a criminal and a communist”, and that the coming Brazilian election was the most important in South American history. He and his international far right movement see Brazil as crucial, having lost the US presidency.

On Brazil’s election day, just weeks before the US mid terms, “unprepared” mesários were amongst those blamed for delays to the voting process, causing lines, waiting times, and ultimately abstentions to multiply.

Second Round

Workers Party’s Jacques Wagner identified reducing abstentions as a key pillar of Lula’s second round strategy.

Andrei Roman, CEO of smaller polling agency AtlasIntel, which has caught the eye by predicting the first round result most accurately, says that in light of abstentions, Lula is stronger than he looks, and that it represents a reserve of potential votes for the second round on October 30.

President of the Superior Electoral Court, or TSE, Alexandre de Moraes responded to the problems faced in the first round, and identified that some areas suffered more than others: “The TSE is already planning and taking all the necessary measures so that the queues that occurred in some polling stations do not happen again in the next round. This will be done so that the voter has a more comfortable vote”, Moraes said, calling voters to participate in the second round.

Moraes said that the problems that caused the queues are being discussed with regional electoral courts.

“The turnout of all voters is very important so that we can once again demonstrate the maturity of Brazilian democracy and complete this electoral cycle of the 2022 general elections”, he concluded.

That the Superior Electoral Court now seeks to act on long lines driving abstentions in the second round confirmed it is indeed identified as a genuine problem, but both the TSE and progressive commentators are wary of saying anything that may look like it undermines the integrity of the electoral system.

In the campaign to reinforce faith in the system, and particularly the electronic ballot, Brazil may have walked into a trap where antidemocratic strategies as old as elections themselves can be deployed with impunity.

We publish this not in certainty that such tactics are responsible for the result, but in the belief that this conversation is better had now than on October 31.