Old-school electoral fraud casts shadow over the October 30th presidential runoff between Lula and Bolsonaro.

A study by ValorData has demonstrated how Bolsonaro campaign misinformation which associated receipt of pensions with proof of voting for the far-right president, brought almost 1 million more elderly people to the polls in the 2022 first round than voted four years ago.

This accounts for some of the “last minute swing” to Bolsonaro which was famously missed by polling agencies. The threat of losing their pensions mobilised over 70s, whom are not obligated, to vote.

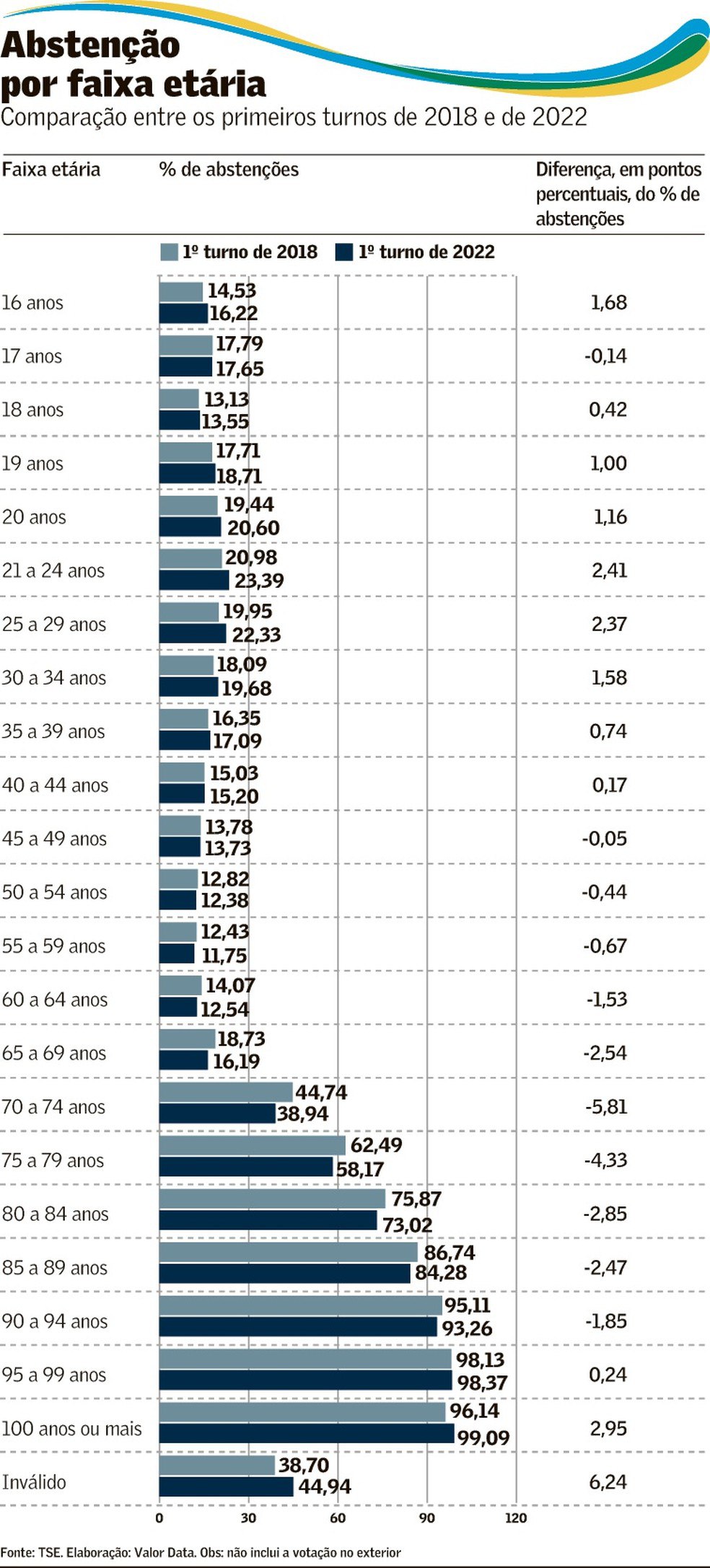

While the number of abstentions for people from 50 to 98 years old fell in 2022, the rate of abstention in other age groups grew.

With no new scandal or information in play during the final days of the election, observers have sought to explain why polls had underestimated Bolsonaro, and Lula, whom was expected to win outright in the first round, came an agonising 1.57% short of avoiding a second round runoff against the far-right incumbent.

Other factors are in play which go beyond normal and legal political campaigning. For example, uneven abstentions damaged frontrunner Lula, and blamed on organised groups of Bolsonaro supporting volunteers causing delays at polling stations. Google’s YouTube platform has also been found to have been pushing Pro-Bolsonaro content to Brazilian voters during the election, a Rio Federal University Study has found. Social media giant Meta has been found to be failing in its promises to control rampant and hysterical disinformation from the Bolsonaro campaign and its allies.

But the “vote 22 or lose your pension” is the most brazen attempt to manipulate the election yet discovered, and amounts to electoral fraud.

The Bolsonaro campaign’s trick dates back to February 3, when the National Institute of Social Security published a new INSS (National Institute of Social Security) ordinance that included proof of voting as proof of life for retirees and pensioners. Thus, election biometrics, for the first time, allowed this group of people to update their records, and prove life, without making a special visit to a bank, for example.

Off the back of this, the Bolsonaro campaign published a brazenly deceptive video, entitled “Prova de Vida” which ended with the message: “For the good of Brazil, vote 22” As a result, the Bolsonaro government electoral manouver brought almost a million elderly out to vote – for him.

The TSE Electoral Court ordered the removal of the video, but not before millions had seen it, believed it, and voted accordingly. It’s effect casts a shadow over the October 30 runoff.

“Now it’s law. In these elections, you who are retired or pensioner can make your proof of life straight from the polls. The federal government did away with unnecessary commuting and made your life easier. Just your vote is enough to guarantee INSS benefits, so you can exercise your right to citizenship with less bureaucracy. For the good of Brazil, vote 22”, stated the campaign video which circulated on social networks.

Before the first round, presidential candidate Simone Tebet’s campaign requested that the video be removed. However, it was only last week, after the vote which narrowly kept Bolsonaro in the race for the presidency, that Supreme Court Justice Carmen Lúcia finally accepted the request. In justifying the decision, the Carmen Lúcia state that the message induces voters to think that proof of life depends on voting for Bolsonaro.

“The video in question presents content produced to misinform, as the message transmitted induces voters to believe that it is possible to carry out their proof of life in the INSS by voting for number 22, which affects the integrity of the electoral process and the voter’s own will to exercise their right to vote”, said the STF minister.

According to the February ordinance, any document that proves the movement of the elderly could be used as proof of life. Vaccination records, consultations with the Unified Health System (SUS), proof of voting in elections, issuance of passports, identity or driver’s cards, among others, can now be used as proof of life. Even with all these documents available to acquire proof of life, the proof of vote was the most publicized by the INSS campaign.

In total, abstention in the first round rose compared to 2018. It went from 20.3% to 20.9%. But it is in the breakdown in age group (and location) where increase in rate of abstention becomes more relevant. While the number of abstentions among 20 to 24 year olds grew by 2.4%, among older voters the movement was opposite. Abstention dropped by 5.8 percentage points in the 70-74 age group, which is significant, as it represents an age group whom are not required to vote, which is obligatory under the Brazilian constitution for younger people.

The Bolsonaro campaign will unlikely pay any significant immediate price for these tactics, and election observers must be aware of the various means by which it seeks to manipulate the result before the October 30th runoff.

This article uses some source material from this piece by Emanuela Godoy for Jornalistas Livres.