Menezes, an economist who works for ActionAid and IBASE, says the data suggests Brazil will return to the UN World Hunger Map. The study, which will be released at the end of this month, raises new warnings.

By Thiago Domenici*

In 2014, Brazil left the list of countries in which over 5% of the population consume fewer calories than recommended and made an unprecedented achievement: it was removed from the UN World Hunger Map. Only three years later, a report by 20 civil society organizations published in July, 2017, warned of the risk of the country returning to the Map. The economist Francisco Menezes, a researcher for the NGOs Ibase and ActionAid Brasil, was part of the team that prepared the report.

In this interview, Menezes, who is also a food security specialist, says that at the end of this month the civil society organizations will release a new, updated report. “Our new warning brings a near certainty with it,” he says. He is nearly positive that Brazil is going to return to the World Hunger Map. “All experiences show that the figures for extreme poverty are closely related to those of hunger.”

A study by ActionAid Brasil shows that during the past three years, 2015-2017, the country moved 12 years backwards in terms of people living in extreme poverty. In other words, more than 10 million Brazilians are now living in these conditions. “This leads us to believe that the correlation between hunger and poverty is strong,” Menezes says, “and that we are, at the moment, in a bad situation which will be reflected in new data in the Family Budget Study (POF), which should come out by the end of the year.”

In the following interview, Menezes explains the combination of factors that caused this situation, which he characterizes as a “state of the lack of social protection”.

Has food insecurity returned to the country?

Last year, we issued a warning to the UN that, if Brazil continued on path it recently took, of a certain abandonment of social protection policies, it will run the risk of returning to the Hunger Map that it was removed from in 2014. We published this report in July, 2017, and a new report monitoring the sustainable development goals will be released at the end of the month. What we warned about last year is now being confirmed.

How did you arrive at this conclusion?

Every 5 years the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE) conducts a study on Brazilians’ food security. This study used to be part of the National Sample Study of Households (PNAD) and is now part of the Family Budget Study (POF). The last study was made in 2013 and published in 2014. Since it is done every five years, the new one is still underway, but the people are in the field and the results should be published by year’s end or in early 2019.

There are some changes in relation to the state of food security among people who have regular access to a sufficient amount of food shifting towards levels of food insecurity. And there is grave food insecurity, which is an expression used to characterize hunger, in which families do not have access to food for a determined period. The grave level of food security in 2013, for example, when the last study was done, was very low. This is why, in 2014, the UN removed Brazil from the World Hunger Map.

Does the data now indicate a setback?

How many people are suffering from hunger? We will have to wait a bit to give a close estimate but past experiences always show that the numbers for extreme poverty and hunger are closely related. So we are nearly certain about our warning.

First of all, you have to consider that extreme poverty has a very strong correlation with hunger. In other words, people who are in the most extreme poverty conditions are strongly vulnerable and prone to hunger and generally suffer from it. This is why it is important to look at the issue of hunger together with the issue of poverty and we have witnessed a very fast increase of poverty in the population and we have the data on this.

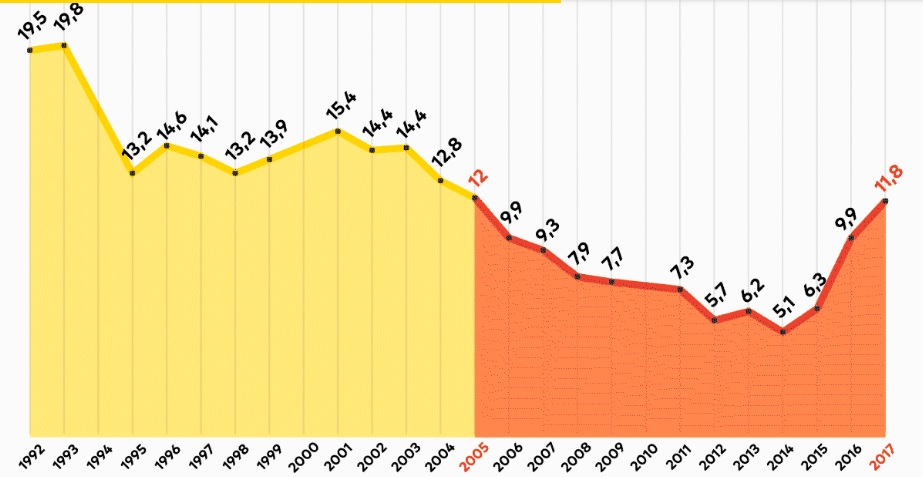

In three years, 2015, 2016 and 2017, we have, unfortunately, moved 12 years backwards in terms of the number of people living in extreme poverty. This leads us to believe that the correlation between poverty and hunger has strongly returned, that we are in a very bad situation at the moment and that this will be shown at the end of the year in the data from the POF study. Extreme poverty is growing faster than poverty, which has regressed to levels from 8 years ago.

Are you saying that the trends show, even if it hasn’t been confirmed yet, that Brazil will return to the World Hunger Map?

I believe that, unfortunately, yes. We still do not have the data from this study that I spoke of. I can say, yes, based on the data from the Continual National Sample Household Study (PNAD Continua), which shows this big increase of poverty levels, which varies from region to region and from state to state. Rio de Janeiro, for example, is suffering from extreme poverty conditions that are highly connected to unemployment levels, which tripled in one year (from 143,000 to 480,000)

Number of People Living in Extreme Poverty (in Millions)

Graph by Bruno Fonseca

What about the other regions?

The Northeast and North have higher poverty levels than the South and Southeast, but the Northeast had a very positive period until 2014 in termos of recuperation, but now we are seeing the situation worsen because it was originally more vulnerable.

What are the causes of this growth in extreme poverty?

There are various causes, in my opinion. First of all, under the guise of fighting what was referred to as a fiscal imbalance, a policy was created that paralyzed the economy, generated unemployment and did not solve the problem of the fiscal deficit. This is one factor and it was caused by the practice of a completely misguided economic policy during the last three years. We can’t forget that in 2015 we experimented with very recessive policies as a strategy for dealing with the challenges that appeared. The paralysis of the construction industry, for example, hit the poor segments of the population hard, leaving a great number of people unemployed or underemployed. The fact that the companies that worked within the Petrobras system and so many others were deliberately paralyzed deepened this scenario. In other words, unemployment cannot be overlooked as a factor in the increase in poverty.

Should the Temer Government’s move to freeze public spending for 20 years be considered as an immediate causal factor for the increase in poverty?

Without a doubt. The constitutional amendment was approved in the end of 2016. If you look at the budget for 2016 in regards to social programs, there already was a strong contingency that year. So in 2016 they were already experimenting with budget cuts. The proposal from 2017 caused enormous cuts for 2018 and beyond. It is what we now call a state of absence of social protection, because funds are lacking on all sides.

In terms of extreme poverty, we feel that there are cuts being made to contingents of families by the Bolsa Familia welfare program who, contrary to what the government claims, are not families who simply failed to meet the program’s requirements but that are the most vulnerable and who generally have more problems with the documentation. Many families that were cut off from the Bolsa Familia program had it as their only source of income or as an important part of their income and this is important in terms of the food security issue in other studies that are underway. We know that the recipients of Bolsa Familia, for the most part, spend the money on food, due to the weight that food has on their household budgets.

Is this point about Bolsa Familia based on research or is it more your opinion?

It is not based on a study but there were 1.5 million families cut off from the program, which you can see from the Government’s own data. In 2018, the government reduced the budget for Bolsa Familia. What is happening, and what we suppose but do not have proof yet, is that a great percentage of these families that were cut off were the poorest families.

Another cause for the increase in poverty are the price increases, not only for food, but for another product which weighs heavily on poor families – cooking gas. The gas price has a big impact on the poorest families. With the generalized fuel price hikes, we are beginning to see the first proof of how this is affecting people. This without out even taking into consideration how fuel price increases affect food prices.

Brazil is one of the world’s largest food producers but people are going hungry. How do you explain this situation?

Brazil, undoubtedly has a relevant capacity for food production. Our problem is not production but what happens when there is deep inequality, including in the countryside.

*This interview originally appeared in Publica and was translated by Brasil Wire

[qpp]