In his landmark work, “A Fantasia Organizada”, legendary developmentalist economist Celso Furtado described the modern history of Brazil as a conflict between internationally-backed monetarist economic strategies and efforts to implement a national development policy. As it becomes probable that US-sponsored lawfare attacks will succeed in preventing Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva, who is leading all popularity polls with double the support of his nearest rival, from running for president this year, Marcio Pochmann argues that it is time for Brazilians, once again, to make a stand for sovereignty. Pochmann, author of 27 books, is one of Brazil’s most renowned living developmentalist economists. This article, translated from Portuguese, originally appeared in Rede Brasil Atual.

By Marcio Pochmann.

Temer throws out Brazil’s sovereignty and protaganism, which picked up steam in the 2000s. On the other hand, he has reignited the rebel spirit which ended the old republic in 1930.

When the first steps were made towards a national industrial development project with the Revolution of 1930, the opposition built a political and ideological vision of submission to foreign capital. Since then, it’s primary goal has been to uphold the elitist form of societal reproduction that is associated with international interests, in opposition to the interests of the majority of the Brazilian people. During the 1940s, for example, this servility took shape in the liberalism of Eugênio Gudin, in defense of the primitive model of agrarian society that was installed by the Portuguese in the 1500s. It recuperated the backwards spirit that was imposed on the country, during the reign of Emperor Dom Pedro II, which stifled the Baron of Mauá’s industrialist emergence, from 1850-1870, and continued through the Old Republic (1899-1930) under the rule of agrarian elites who buried the positivist national modernization project.

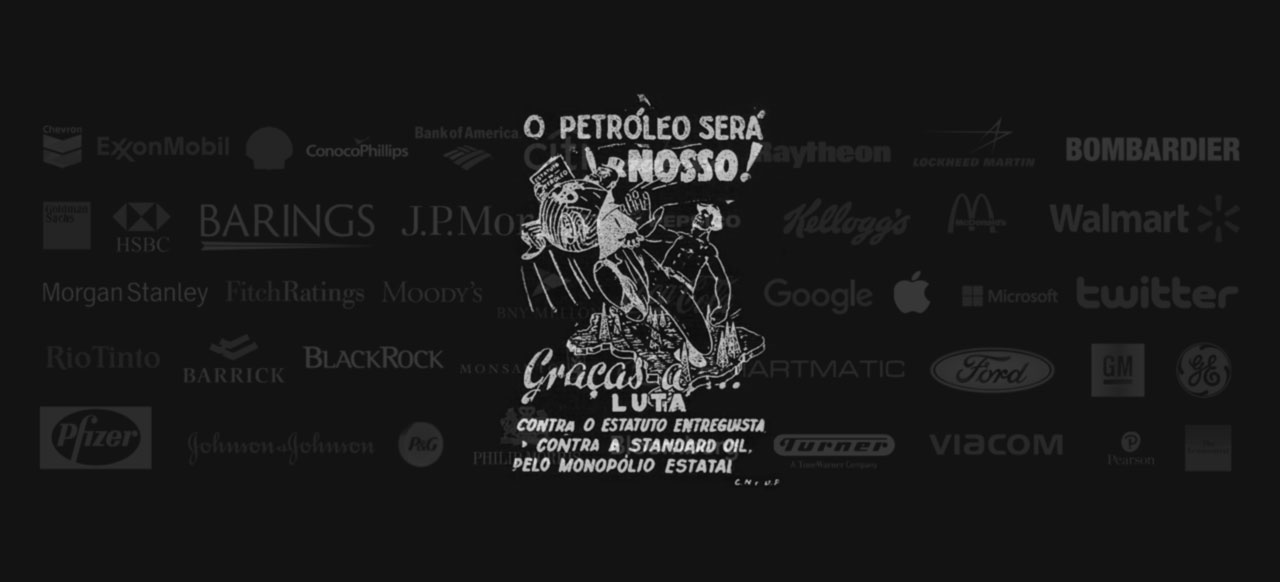

In reaction to the “Petroleum is ours” campaign in the beginning of the 1950s, the movement to defend systematic privatizations of the productive system at the service of foreign capital established its national dimension. In this manner, it promoted a growing embarrassment with Brazilian development and the prevalence of the status quo among the elites and servile governments.

Under Temer’s government, submission to international capital’s domination, exploitation of natural resources and national projects has returned with undeniable force. Brazil is throwing away it’s entire strategy of sovereignty and protaganism that was built on new foundations during the beginning of the 2000s.

The dismantlement of the national defense system, with the canceling of the Brazilian nuclear program, the delivery to foreign interests of the Alcantara rocket base, which is one of the World’s best geographical locations for launching satellites, and the ending of production projects with shared technology, such as the military fighter jet project are examples of this process. The selling off of Embraer, the third largest aerospace conglomerate in the World, to Boeing, is one more nail in the coffin of national sovereignty. Another example is the Petrobras petroleum company’s privatization process and the immediate delivery of the pre-salt petroleum reserves, with an estimated worth of $1 Trillion dollars, to foreign companies like Chevron and Shell for only $ 6.5 billion. This has caused a paralyzation of the ship building industry, which had been rebuilt in recent years due to Petrobras’ demand for ships needed for the unprecedented and daring extraction of petroleum from the offshore, pre-salt fields.

Glysophate, which is being banned in Europe, will now be legalized in Brazil for Monsanto. The migration of the government computer systems from open source software, used since 2003, exclusively to Microsoft products will raise public spending by R$140 million/year and destroy the security of Brazilian government information. The government is moving to deliver Latin America’s biggest energy utility, Electrobras, to the private sector for R$20 billion, when it has been appraised at R$370 billion. It is also dismantling private Brazilian energy companies and attacking the largest national meat producers.

The asphyxiation of State financing for constitutional amendment 95, the dismantlement of national social and labor policies through so many reforms, such as the labor law reforms and the pension reforms, which are still underway, illustrate that the economic interests which run the country didn’t just produce the coup of 2016 to sustain the moribund Temer government. It still needed to destroy the possibility of Lula running for president and deconstruct the chances for the PT party, through a democratic process, to interrupt Brazil’s submission to foreign capital. With these moves they may be fostering the rebirth of the same vanguard spirit of 1930 that, perceiving the impossibility of dispute through democratic channels, did not accept the election results and led the revolution which freed Brazil from the Old Republic’s submission to international capital. Could this represent an opportunity to overcome the coup of 2016, which ended the democratic cycle of the New Republic? Now, the personalities who ran the Republic’s institutions possess the historic responsibility of guaranteeing the continuity of the fragile Brazilian democracy.

Marcio Pochmann is a professor at the Institute of Economics and researcher at the center for Union and Labor Economy Studies at Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP)

[qpp]