There is one person who believes that Ciro Gomes will be the next president of Brazil. His name is Ciro.

18 months out from the 2022 presidential election, Gomes sits on 6% in the latest Datafolha polls. This figure is less than half of what he achieved in the 2018 first round, and a withering 35 points behind former president Lula da Silva. Still, it is very early days.

Gomes’ political reputation was built in the 1990s, first from his popularity as a young governor of Ceará, and then as Minister of Finance under Itamar Franco, during which the Plano Real currency programme was implemented. He would later serve as Minister of National Integration in the first Lula administration, and built a certain level of cross party support.

He also has a reputation as a loose cannon, an opportunist, and a political chameleon. 63 year old Gomes has been affiliated to a succession of political parties across the ideological spectrum since entering politics in his early twenties; PDS (formerly the ARENA dictatorship government) 1982–1983, PMDB (the dictatorship’s approved opposition) 1983–1990, social democrats turned neoliberals PSDB 1990–1997, left wing PPS (now third way Cidadania) 1997–2005, the centre-left socialist party PSB 2005–2013, centrist republican party of the social order PROS 2013–2015, and the democratic labour party PDT 2015–present.

By then a presidential candidate in waiting for the PDT, during the 2015/16 coup period Gomes talked the talk; of developmentalism, of sovereignty, and built some trust on the left at a time when most media was running with the narratives of the coup and neoliberalism. Presenting himself as an heir to Dilma Rousseff’s one time mentor, Leonel Brizola, Gomes was open in opposition to her impeachment, called it a coup, and publicly identified the geopolitics behind it when that subject was practically taboo.

Yet as her ouster came closer, and with an eye on 2018 election, he became increasingly critical of the Rousseff-led government. But it was with Lula’s prosecution that he saw what he believed was his moment, and he was positioned as a centre-left alternative without the baggage of the Workers Party, and not for the first time.

PDT is to the right of the PT in most regards and is somewhat incoherent ideologically, as exemplified by Wall St-backed liberal Tabata Amaral and the RenovaBR movement she fronts. In an intriguing plot twist, for the coming election PDT have contracted strategist and PT’s former “political midas”, João Santana, who had been jailed by the Lava Jato investigation and sat out the 2018 election. Veja magazine excitedly called Santana a living archive of the Workers Party, no doubt hoping he has useful scandal up his sleeve. Santana said in his first interview since release from prison, for TV show Roda Viva, that he considered a combined Lula-Gomes ticket unbeatable.

Despite subsequent meetings between Lula and Gomes following that interview, he quickly returned to attacking the former president. His most recent diatribe against came in Valor magazine, where he announced “I’m going after Lula, the biggest corruptor in Brazilian history” and made a succession of allegations, such as claiming that Lula and PT are responsible for Bolsonaro, accusing them of an “unsustainable national-consumerism” and insinuating that the annulment of charges against the former president do not signify his innocence.

Ciro has been identified by some as Brazil’s wing of a culturally conservative left now in ascension, yet along with his new role as an anti-Lula attack dog, he is making play to the right-wing so called Centrão. Gomes is explicitly seeking alliance with hard right dictatorship heir party Democratas, a leading force behind the 2016 coup and part of Bolsonaro’s original coalition.

Lula has also been talking directly with PDT leadership, but party president Carlos Lupi has maintained that Gomes would be their candidate in 2022, predicted a second round runoff between him and Lula, and insisted that despite Ciro’s attacks, that Bolsonaro, and not Lula was Brazil’s public enemy number one.

Ciro’s explicitly centre-left position of 2015-18 (he would correct those who referred to him as a left candidate) has been jettissoned, and with it commitment to unity of progressive forces for the defeat of Bolsonarismo. By trying to build his own alliance, excluding the biggest party in Congress, Gomes is a principle obstacle to a frente-ampla, and his tactics appear designed primarily to prevent a possible first round win for Lula.

Whatever Ciro Gomes now is, it appears to have little to do with the left at all.

Friend and ally of PDT founder Leonel Brizola, Vivaldo Barbosa said: “PDT and Ciro are already on the other side. They are no longer labour and Brizolistas. It reminds me of a line by Drummond: just a picture on the wall, and how it hurts.”

The Candidate

“He’s in prison, idiot!” was the defining statement of Ciro Gomes’ 2018 presidential campaign, referring to Lula da Silva.

Following Lula’s eventual barring from the race, overtures to form a joint PT-PDT ticket came to nothing, and mutual distrust between the camps only grew. It was as if Gomes expected them to step aside, and was infuriated when they did not comply.

In 2018 there was a rationale that antipetismo, and not Bolsonaro, was the electoral opponent, and that it had become too strong for the Workers Party to defeat. Their candidate would be facing an unstoppable coalition of anti-PT feeling, whereas Ciro and the PDT’s credentials for this scenario were well articulated in this piece which was published by Brasil Wire at the time.

Many who would have normally supported the Workers Party candidate opted to vote for Gomes in the first round, convinced that he stood a better chance in the runoff of defeating Bolsonaro than Fernando Haddad.

There was no doubting antipetismo’s strength. It had transformed from embedded conservative sentiment to inchoate political movement, almost a party in its own right. Once announced as Lula’s replacement, Haddad was bombarded with spurious corruption allegations, all of which evaporated one by one once Bolsonaro had been elected. Lava Jato judge Sérgio Moro was later found to have leaked stories deliberately during the election to aid Bolsonaro’s campaign.

Abstentions rocketed in the 2nd round, attributed in part to this phenomenon, with Liberals who could not stomach Bolsonaro voting blank/null rather than back another “corrupt” PT candidate with the party’s reputation obliterated by the now disgraced Lava Jato.

Although polls showed some evidence of it, we will never know if Gomes would have done any better than Fernando Haddad, who got 47 million votes after being named as the candidate only six weeks before.

But many of those who went with Gomes in the first round on this basis would not do so again. He alienated many of them by leaving the country, taking a vacation in Paris after the first round, without first endorsing Haddad for the runoff against Bolsonaro. This was considered betrayal. Then upon his return a few weeks later, with half of Brazil still in deep despair, Ciro reassured a group of investors that the neofascist represented “no threat to democracy”, and that he was not going to stand in fierce opposition to the president elect.

A little known historical curiosity is that ex US Democrat and UK Labour party online organiser, political and technology consultant Zack Exley, was parachuted in to assist Ciro Gomes’ campaign. At soirées in the downtown São Paulo apartment of a prominent US journalist and writer, Brazil’s invited left-wing parties rubbed shoulders, with the exception of the PT. Although seemingly of a more informal advisory nature, the mere presence of US left campaigners is noteworthy; Gomes is no Bernie Sanders.

The same journalist also favoured the Marina Silva campaign in 2014. Ex-Lula minister Silva was a similar centre-left candidate to Gomes, who, with 21%, and US State Department support, succeeded in splitting the progressive vote and preventing a first round victory for Dilma Rousseff. Silva then abandoned all pretensions and backed PSDB neoliberal Aécio Neves in the second round. An indicator of their internationalised campaigns, both Silva and Neves received incongruous social media support from US celebrities who were unlikely to have ever heard of them, as did Gomes four years later.

2018 was Ciro Gomes’ third shot at the presidency. Twenty years earlier he ran on a PPS ticket and came third with 10.97% behind Lula/Brizola’s 31.71% and Fernando Henrique Cardoso with 53.06, which was enough to take the election in the first round, with some special help from Robert Rubin’s all-powerful US Treasury.

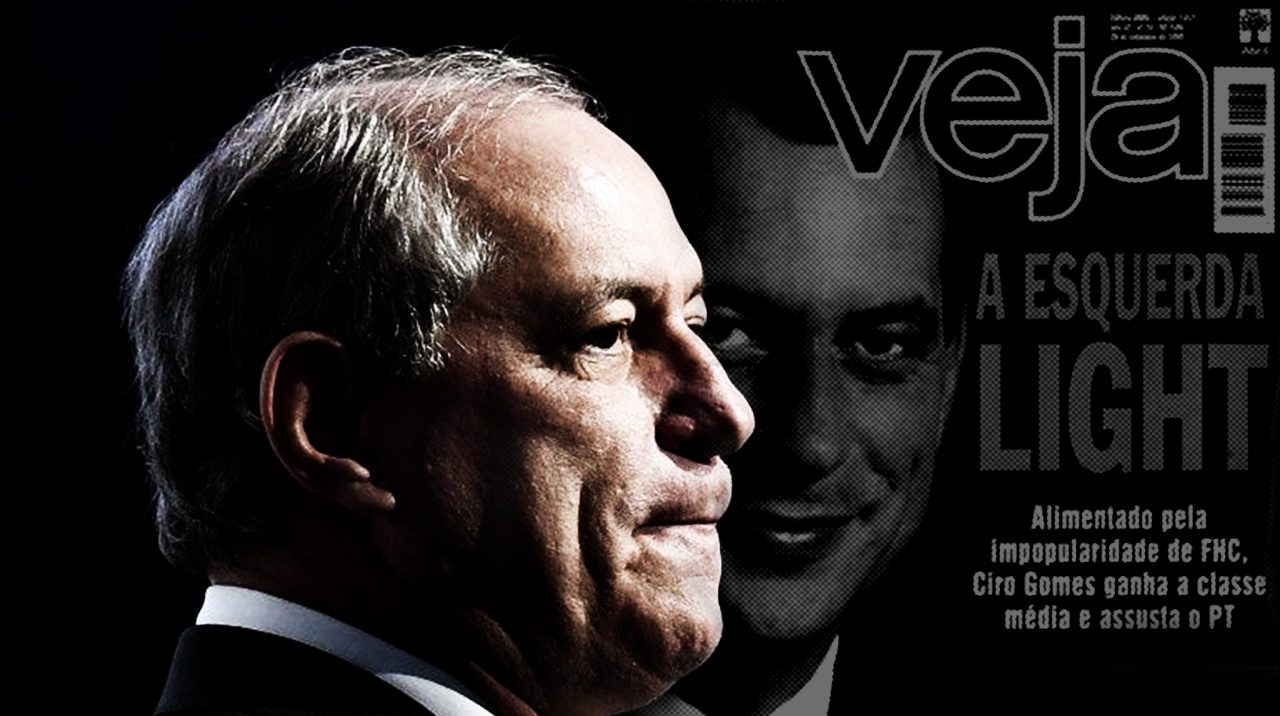

After the currency crash and economic crisis that followed the re-election of FHC, Conservative Veja magazine was already pushing Gomes as the “Esquerda Light” with cover story depicting him as the Workers Party’s arch nemesis. Yet after what looked like a strong candidacy, in 2002 the pragmatic, gaffe-prone Gomes would increase his vote by only 1 point to 12%, with Lula going on to emphatically defeat PSDB’s Serra in the runoff, ushering in the PT era. Gomes backed Lula against Serra, and went on to join his first government.

He did not contest the presidency again until 2018, where he equalled his 2002 result of 12%. After her own vote collapsed to 1 point, three time candidate Marina Silva has now also signalled her support for a PT-free alliance behind Ciro.

Yet three years after that last run, antibolsonarismo is a far stronger electoral force than antipetismo, and he will not have that working in his favour in competition for the progressive vote. 2022 is likely to be his last shot at the presidency.

There is every possibility that Ciro Gomes, if elected, could be, or could have been, a very competent president of Brazil. Yet with a career of switching parties, positions, and these latest overtures to the children of the dictatorship, there is little evidence that his political ambitions are motivated by ideology or principle.

[qpp]