In 1947, the Brazilian artist Candido Portinari gave a talk at the Centro de Estudiantes de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires called ‘The social meaning of art.’ The environment was relaxed, with young people clustering around eagerly to hear him speak; later Portinari would refer to the event as a ‘conversation among friends’. Addressing the crowd, Portinari said that ‘the development of any human activity is linked with historical, political, and economic events’; expanding on this to discuss art, he said that ‘social painting is that which intentionally directs itself to the masses, and painters must possess both artistic and collective sensibility.’ The applause was resounding.

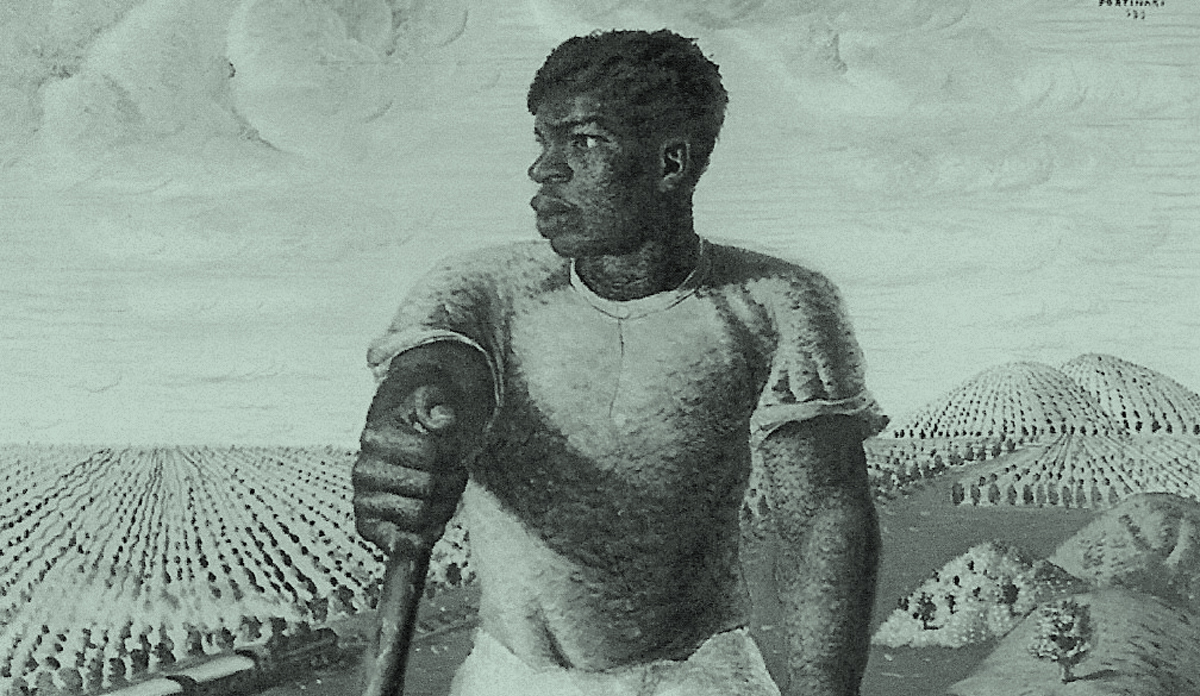

When he made these points, Portinari was already an established artist. Throughout the 1940s, his paintings had been shown in galleries and exhibitions in the United States and France, the most famous being his ‘War and Peace’ panels in the United Nations building in New York and his mural in the Library of Congress in Washington DC. Using a palette dominated by earthy reds, browns, and yellows, Portinari’s giant canvasses depicted black workers on the coffee plantations and poor farmers in the dry Northeast of the country. His people, instantly recognisable by their huge round heads, short bodies, and massively over-sized hands and feet, were shown hard at work in monotonous activity. Western critics praised Portinari’s ‘realism’; in his paintings, they noted approvingly, the ‘negro’ and genuine Brazilian life were openly illustrated for the first time.

This praise was merited, but it was also incomplete. Portinari held and still holds a claim to being the best-known Brazilian painter – his works are much loved by critics, the government, and citizens both in his own country and abroad. But his paintings are not an integral part of Brazilian culture solely due to their depiction of the black and the poor.

Portinari’s paintings are also deeply Brazilian in their political context, though he did paint the ‘common people’, Portinari had a specific conception of his own relationship as an intellectual to this people. He was a communist, yet his version of the left co-existed with the ‘leftist’ dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas. His desires to both shape Brazilian art and transform the way people thought about society were riddled with ambiguities. But the reason Portinari remains so interesting is precisely because of these tensions in his life and work, bound inextricably with Brazilian politics and the trajectory of his nation.

The Rediscovery of Brazil

Portinari was born the son of Italian immigrants in a coffee fazenda near the village of Brodowski, in São Paulo province; this environment would define him. In one of the poems Portinari wrote late in life, he said that ‘I came from red earth and the coffee plantation’, and he spent his life painting those themes.

As a child, his inclinations towards art and artisanry were so marked that he did not even attend primary school, instead passing the time helping his father and making sketches. When he was 14 a group of Italian painters visited Brodowski to help restore the local church, and Portinari was allowed to ‘help’ with scaffolding and frescos, though in practice this meant painting a few stars on the ceiling and chatting with the workers. Luckily, he won a place at the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, afterwards getting a job with a photographer enlarging photos as paintings and making an early reputation as a portrait artist. When he wasn’t working on close-ups of rich clients, however, Portinari preferred precisely the opposite: vast landscapes making heavy use of brown-red, with the people within them so tiny the pictures assumed an almost surreal quality. His circumstances were humble; he would give people paintings in exchange for art supplies, and sleep on the floor of friends’ studios or apartments

The years of hard work paid off. In 1928 Portinari won the Prix de Voyage, a scholarship enabling him to travel to France, Italy, England, and Spain. Artists awarded a similar opportunity on the continent had used the opportunity to buy up as many paintings as possible, and paint frenetically; despite his famous work ethic, however, Portinari did no such thing. The period was for him instead one of quiet transformation, taking place under the surface and separately from the production of work (although his time was productive in at least one way: while in Paris, he met an Uruguayan named Maria, whom he would marry.)

It was during this time that he realised what he wanted to paint, and how he wanted to paint it. As Portinari put it in a 12th July 1930 letter sent from Europe: “From here I see my land better, I see Brodowski as it is. Here I have no desire to do anything. I am going to paint the people [of Brodowski], with their clothing and their colour.” As such, though he saw a lot in Europe – he was particularly impressed by the elegance of Italian renaissance paintings, the thin blank faces of Modigliani, and the horror of Picasso’s Guernica – his output was small. Once back in Brazil, however, Portinari set up a studio and attacked his canvasses with a new sense of purpose.

Portinari’s realisation that his own country could be the subject of art mirrored larger artistic trends. The 1922 Modern Art Week in São Paulo set the trend for a reinvigoration of art true to the nation’s essence. In a comic wink to the nation’s indigenous, intellectuals asked: ‘Tupi or not tupi?’. The poet Mario de Andrade widely pushed the idea of a ‘descubrimento de Brasil’, embarking on ethnographic trips in 1927, 1928, and 1929. The next two decades saw this push towards the ‘rediscovery’ of Brazil both deepen in scope, and widen into other media. A new literary movement by Jorge Amado, Graciliano Ramos, José Lins do Rego and Erico Veríssimo emphasised the common people; blackness became a theme in artists like Jorge de Lima, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Oscar Fernandes, and Gilberto Freyre. Traditional musical traditions like samba were recuperated and given a prominent role in the national identity.

This ‘rediscovery’ was accompanied by the idea of social improvement. In a famous Rio de Janeiro conference in 1942, Mario de Andrade said that the first goal of culture was ‘the political and social improvement of man’. Cultural renovation could not avoid the economic: the financial crash had had its effects in Brazil, ‘nation of planters and industrialists’, just as in the rest of the world. Life in the sertão, the vast dry hinterlands of the northeast, had already been difficult; now it was near impossible, and droves of immigrants were flooding south to wealthier and more temperate cities like São Paulo. Much of the work of the new artists conveyed this dryness: Brazil, stereotypically a land of rich tropical abundance, could also be dusty, hard, and fruitless, as described in Graciliano Ramos’ Vidas Secas.

Portinari’s work can be seen in light of these trends. From the 1930s onward, his figures would increase in size to take up almost the whole canvas. His people were now subjects, their natural environment receding in importance. This period also saw the beginning of his distorting effects – the exaggeration of head, feet, and legs in his paintings. In Brazil this has been attributed to many causes, ranging from a childhood limp playing football (art as compensation for reality’s deficiency) to the deformed feet of workers seen on the café fazendas (art as exaggeration of reality’s pain). Whatever the case, Portinari’s connection to the sensuality and tangibility of these humble feet is clear; in his 1958 autobiography Retalhos da Minha Infancia he writes: “Feet that could tell a story impressed me… feet similar to maps: with hills and valleys, and furrows like rivers…”

Portinari wanted to tell the story of humble people, the people who made up the nation. Yet his work was not at first accepted. Where previously he had received critiques that he was ‘demoralising Brazil’ with his bleak landscapes, now people did not understand his work on a purely aesthetic level. ‘They said it was only ‘big foot’ painting,’ he said. ‘They said I was alright at painting portraits, just a head. But with my other pictures, people would come and say: Nice work, the head isn’t bad, but why the big feet?’

Again, however, his luck would change. In 1935, Portinari’s Café, a busy picture showing life on a café plantation, with men and women performing the back-breaking labour of carrying sacks of coffee beans, received an honorary mention at the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the Carnegie Institute in New York. This acclaim abroad made Brazilian critics at home take another look at ‘their’ painter – this time, they found more to like in the vision of the nation Portinari presented abroad and at home, big feet included.

Painting and the Brazilian Left

The intuition that there was a nation to be ‘discovered’, linked to the people, was not a purely artistic one. A coup d’état in 1930 installed as president Getúlio Vargas, a man marked by his populist discourse. Though he had risen to power by working with landed plantation owners, Vargas made it clear that his government would depart from their ‘café com leite’ politics. Brazil was bigger than this, and needed a new infrastructure favouring the growth of private industry and corporations to help break up the old interests. Promoting the development of the factory and the modern worker through heavy state intervention was, according to Vargas, the best way to help the nation.

Portinari became the official artist of the regime, chosen to inhabit this role thanks to the honours he had received abroad for Café and other paintings. Under Vargas he would produce one of his most impressive and enduring works: the 1939 Panel of the Economic Cycle murals for the Palace of Culture (now the Ministry of Education and Culture). It is tempting to draw a comparison with the murals of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco on the walls of the Mexican Ministry of Education, as these were also produced with a social message; however, Portinari was not interested in creating bold, polemical art focused on revolution, as they were. His work used softer colours, organised its space more systematically, and focused not on his country’s history of violence but rather on its peaceful economic development.

Meanwhile, political storm clouds were gathering. In 1937, facing the prospect of having to leave power because of provisions in the Constitution legislated by his own government four years before, Vargas implemented his infamous Estado Novo, dissolving Congress, calling off elections, declaring a state of emergency, and constructing a censorship-driven police state. This highly ambiguous entity, with heavy trade links to Germany and political links to Italy during the war, ultimately sided with the Allies, and particularly the USA. Despite his repressive tendencies, Vargas improved labour legislation and reinvigorated the national economy, such that even today his legacy is contested. Post-war, however, pressures towards a return to democracy were strong, and in 1945 the middle class forced the Estado Novo’s end.

During the Vargas years, the Brazilian Communist Party had been made illegal, and activity was clamped down on heavily. With ‘redemocratisation’, however, in 1946 Portinari was able to enter the party, in which he’d always had an interest. He attempted to get involved politically, running twice for candidate for the Legislature, first as federal deputy and then as senator for São Paulo, but was both times unsuccessful. At any rate, the very fact that Portinari joined this party, rather than one of the three dominant parties fighting it out post-Vargas, illuminates his mentality. The Communist Party was a tiny minority, with only about nine percent of the vote. But it was popular with the country’s avant-garde, and intellectuals and artists within it enjoyed their self-imposed role of directors of popular sentiment. Portinari was no exception. In his talk “Sentido Social de Arte”, he emphasised that a painter had to be technically good – if not, he might as well shout his social ideas in the plaza instead of creating art. At the same time, however, the artist had also to connect to popular sentiment through his suffering, serving as a one-person representation and interpretation of larger societal struggle.

From the 1940s onward, Portinari would grow more daring in his art, applying paint with a thick brush and palette knife. This art was often more appealing to the critic than the ‘common man.’ Painting, his medium of choice, itself held a strange status opposed to other graphic arts; collective traditions in wood and printmaking had long existed in Brazil, cultivated particularly by those in the Northeast who used woodcuts to illustrate stories they were unable to write. Yet though Portinari preferred painting, and ‘modern’ painting at that, it is clear he thought of the ‘people’ as his audience, and his themes remained social ones.

The question always hovered over his work: was art meant to be inspired by the popular, or to shape it? Perhaps both, contradictory as this might seem. Artistic ‘communism’ was common currency on the Brazilian left, in which the goal of elites, as de Andrade put it, was “to promote the emergence of those segments of society in shadow, putting them in a condition to receive more light.” The lack of knowledge they had of the ‘common people’ was something to be rectified, but so was the public consciousness, which could be shaped through, among other things, social art.

During this period Portinari travelled widely, and just as he had learned from his European tour, he also learned from other countries in the New World. Apart from his Northamerican tour, he also visited neighbouring countries like Argentina, where he was treated with great respect. At a literary gathering in his honour, for instance, the poet Nicolás Guillén wrote “Un Son para Portinari”, which would later gain popularity throughout the continent when sung by Mercedes Sosa. The importance of Portinari to both two nations remains clear to this day; a lavish 2005 collaborative project between Brazil and Argentina called Candido Portinari y el Sentido Social del Arte focuses on the deep links between the left-wing ‘dictatorships’ of Vargas and Perón, between São Paulo and Buenos Aires, and between intellectuals on the left in both countries.

Yet despite the praise he received, and the project to which he was committed, there are occasional signs that as he grew older Portinari himself began to question the ‘social’ role of painting. “Painting, which was previously the greatest vehicle for the propaganda of ideas, today itself requires an enormous propaganda to survive,’ he wrote. ‘Previously it served religion or the State; today it does not serve anybody. Other media more direct and efficient have substituted for it, such as the cinema, television, radio, and newspaper.”

Perhaps the happiest moment in Portinari’s later life was when he went back home to Brodowski, to cover the interior of the local church with simple, colourful murals removed from immediately ‘political’ concerns. Then, as throughout his career, Portinari would employ dramatic yellow paint, though he knew that it contained lead; ultimately he would die from its effects.

The Ambiguity of ‘Realism’

The new path that Portinari, and his country, were trying to trace was a shaky one. Portinari’s patron Vargas would return to power in 1951, once again pushing a nationalist policy free of foreign influences, and founding companies like the Brazilian oil giant Petrobras. Threatened with a coup attempt on the palace, he would preempt fate and calmly shoot himself in the chest with a Colt, leaving behind the lines: “Serenely, I take my first step on the road to eternity and I leave life to enter history.” But the nationalism he represented was embraced fiercely by the people for years after, a nationalism which would take on its full and terrifying consequences with the take-over by armed forces of the country from 1964 – 1985.

Portinari’s use of realism illustrated the ambiguities of Brazil. Though paintings of workers’ struggles and the poor could have been deemed ‘communist’, such subject matter was always in danger of devolving into popular kitsch if it based itself on traditional bourgeois representational methods of realism. The solution was that if realism was truly to be attuned to the social it had to use avant-garde techniques. The discovery of the ‘popular’ thus entailed the use of elite methods. In the end, Portinari’s nationalism served the purposes of the elite artistic world in which he operated more than any ‘people’ this elite imagined.

Portinari lived in a period of Brazilian history during which the cause of the ‘people’ was co-opted with striking ease, with nationalism being used as a keyword by everyone from communists to the military. The ambiguity of his work, and the Brazil in which he lived, lies with the enduring question of whether its constant search to represent the social realities of people and nation was ultimately concerned with these realities secondarily, as stepping stones to the more private interests of art and politics.

This article was originally published in the Sounds and Colours book Brazil, a collection of articles, photos and illustrations depicting Brazilian culture.