Unlike Walesa, Lula never lost his class consciousness or political commitment

August 31st marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the Gdansk shipyard wildcat strike, led by Lech Walesa, who went on to become Poland’s first post cold war president, collaborating with US intelligence officials and Breton Woods institutions to transforming his nation into a dependency capitalist vassal state. In 1980, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was another of the world’s most prominent labor union leaders. He also went on to become president of his nation, but, politically and economically, these two leaders could not be more different. In the following article Polish journalist Maciek Wisniewski traces the trajectories of the two former union leaders.

by Maciek Wisniewski

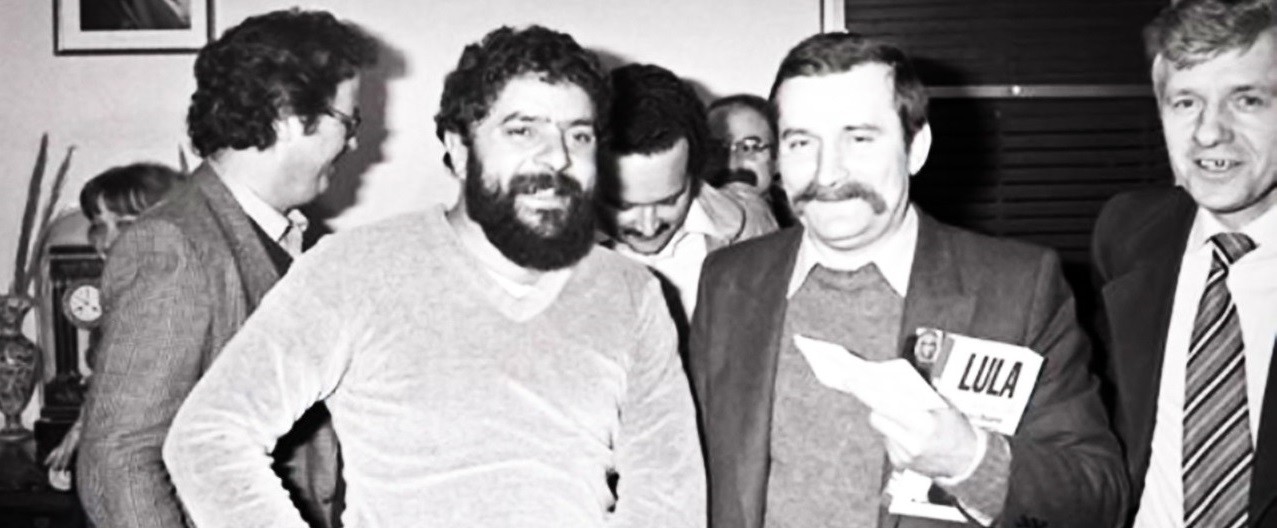

On September 29, 2011 Lech Walesa presented Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva with a Walesa Foundation award in recognition of having acted to reduce social and social inequalities and strengthen the importance of developing countries. The former Polish President (1990-1995) and 1983 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate met with the former President of Brazil (2003-1010) in Gdansk, where in the early 1980s Walesa led the strikes that ushered in the first independent union of the socialist bloc.

Even though both leaders share the same roots, coming from humble families and rising up as workers and union leaders who fought against dictatorships, the different realities of their countries made it difficult for them to understand each other. As economist and dependency theory founder Theotonio dos Santos points out, the main political vectors in Eastern Europe and Latin America were completely different: while in Poland capitalism and the free market were synonymous with freedom, in Brazil, the free market came with dictatorship and freedom was associated with socialism. In the 1980s, Lula sought out Walesa. During that period, comparing themselves to and aligning with other labor movement stars was important to their struggles. They met, but Walesa said he wanted to abolish communism and Lula wanted to establish it. There was no empathy between them. Nevertheless when the military regime in Brazil ended in 1985, Walesa sent his colleague a warm letter. However, after Poland transitioned to democracy in 1989, the Solidarity leader was proud that he had become president and Lula had not.

This was a sad watershed for Walesa though. Once in power, his popularity nosedived. His individualism, arrogance and argumentative nature caused him to lose the election for a second term, and he is now remembered as one of Poland’s most unpopular politicians.

On the economic front, he pledged to restore capitalism. His faith in self-regulated markets and the mantra that inequality is good for the economy was typical of the end of history period. With the population plunged into post-socialist trauma, he opened the door to neoliberal reforms and shock therapy. To facilitate this, he allowed union busting. To Walesa, unions were good at abolishing communism, but in capitalism they were no longer useful.

He stopped fighting for the interests of the workers and began to defend those of capital, burying the whole idea of social solidarity in this path. The result: huge social inequalities, deindustrialization, high unemployment and a Poland that was submissive to global capitalism as a periphery state.

Theotonio dos Santos recalls that when, after 1989, he said “welcome to underdevelopment,” to his colleagues in Poland and Hungary, they understood nothing.

Once retired, Walesa dedicated himself to personal enrichment and marketing through his foundation. He became a lecturer-mercenary and advisor to the highest bidders. So it was in Mexico, in July 2005, when he attended the celebrations of then President Vicente Fox, who was leaving the government after exposing his curious thesis that using democracy is a possibility directly proportional to the size of one’s checkbook. Or when, more recently, he sold his image to a corporate retail chain known for massive labor rights violations.

Lula’s path to the presidency was more sinuous, but once in power he demonstrated that it was possible to think about capitalism and democracy differently -far from anti-capitalism and with all the limitations of the society in which we live – and challenged the neoliberal dogmas of his predecessor Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Theotonio dos Santos is a fierce critic of the supposed continuity thesis between Cardoso and Lula). Lula thought that one of the biggest problems of democracy and capitalism was inequality and dedicated himself to fighting it. This lifted millions out of poverty and guaranteed the country’s economic success. This was recognized by Cardoso himself, with a peculiar compliment, when he said that Lula was a Walesa that worked. But this was a long time ago. He took another path and ended up in another place than Walesa. There is nothing to compare, says Theotonio dos Santos. It is clear that Lula’s policy was not free from contradictions. But unlike Walesa, Lula never lost his class consciousness or political commitment. Subsequently, at the end of two terms, his popularity rate was over 80%. On that date in 2011, it was Walesa who now sought out Lula. Praising him, he tried to relive the similarities and support his success post factum. He even admitted that it was Lula, and not him, who was right about capitalism. Due to his arrogance, it sounded like a warning about the end of the world. In the meantime, what has surely come to an end are any comparisons between these two former presidents.

This article was translated by Brian Mier and can be seen in Portuguese in Carta Maior here.

[qpp]