Narcos is not a documentary and purely as televisual entertainment it is difficult to dislike. It is directed by the talented Brazilian José Padilha (Bus 174, Tropa de Elite) and also featuring fellow countryman, Tropa de Elite’s lead Wagner Moura (Elysium, Praia do Futuro), who shines as Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar. Narcos is a stylish, visually & musically absorbing high-stakes true crime drama, recalling at times 1980s cult Miami Vice. Though the standard appears to dip following the exit of Padilha from the director’s chair after episode 2, regardless, style and production are at times as good as anything out there.

However, just minutes into the first episode something is wrong. Heroic narrator, DEA agent Steve Murphy insists in his rusty southern drawl that “Sometimes bad guys do good things”. Murphy was referring to Chilean Fascist Dictator Augusto Pinochet’s post-coup massacres of local cocaine producers & smugglers.

It may have gone practically unnoticed, but this moment set a tone which also enabled subsequent misrepresentation not only of the story in Colombia, but of others, such as Nicaragua. I hear you – we can’t be too hung up on facts, Narcos is just a drama loosely based on real events – but shows like this help shape the worldview of their audiences in sometimes unseen & unexpected ways.

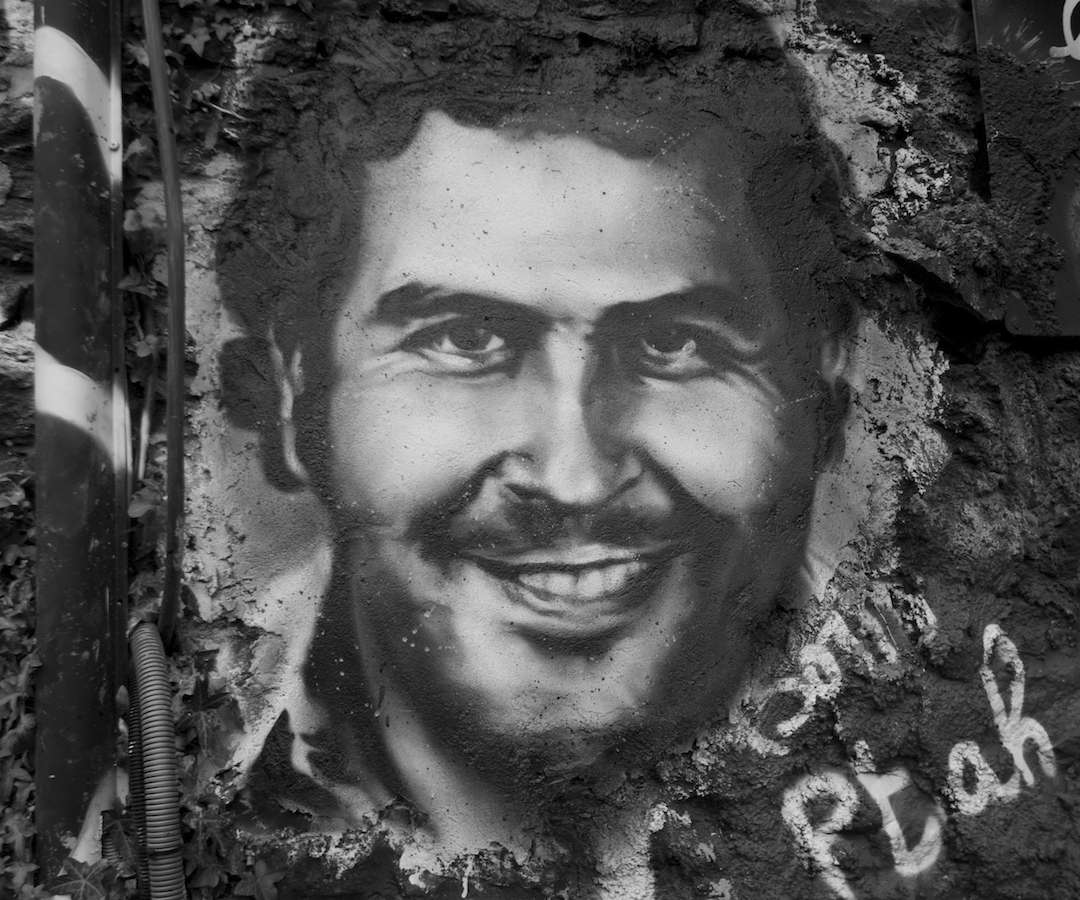

El Patròn del Mal

Though well received in many quarters, some were disappointed, with one review even likening it to a dramatisation of Escobar’s Wikipedia entry.

Many critics of the show have pointed to the non-Colombian actors accents and mannerisms, but my own initial concerns lay elsewhere. My principal reservation was that this is a Colombian story, told from a U.S. DEA perspective, directed by a Brazilian.

In Colombia itself the show has been almost universally derided and those with an interest ought to be asking their opinion first and foremost. A scathing critique ‘Narcos, una decepción’ appeared shortly after the show became available.

Many recommend “Escobar, el Patròn del Mal” as a superior rendition of this story from a primary local perspective, and therefore without the heavy-handed U.S. propaganda aspect. Indeed nowadays it seems impossible to depict the world outside North America without these kind of elements – in this case glamourisation & endorsement of the catastrophic ‘War on Drugs’ in Latin America.

At best Narcos is a revisionist “propaganda fable” like Argo, at its worst displays the brazen disingenuousness of Zero Dark Thirty. This is especially true in regard to the normalisation of DOJ intervention in other countries.

Judicial sovereignty is tossed aside as if mere inconvenience. Legal interference by the United States is extremely relevant right now, especially in relation to ongoing corruption prosecutions in Brasil. In Narcos it goes unquestioned – a one-sided extradition agreement is presented as if honourable, logical and fair, just minutes apart from a scene where resistance to imperialism is infantilised by a character, high on cocaine & receiving oral sex, shrieking anti-yanqui slogans live on the radio.

Perhaps the scene where the DEA becomes the go-to source for the best quality cocaine in North America is coming up later in the series.

Elsewhere the heroic narrator, DEA agent Steve Murphy (who arrives in Colombia wearing his lack of Spanish like a badge of honour) disdainfully refers to Communist militia group M-19 – “A group of schoolteachers who had read too much Karl Marx for their own good” with their “Slogans about redistribution of wealth…which was bullshit.”

Another editorial aspect of note was the relentless repetition of the “good honest men who just want to make their country great” versus “corrupt populists” trope. This is a particularly relevant inclusion right now, right across the region.

If we’re to concede that – for the necessities of funding – these shows and movies are at least in part propaganda we should be able to deconstruct them as such. An argument made in the show’s defence is that the director is Brazilian. Many would have anticipated that this would protect the story from the kind of concerns described here, but this also falls into the trap of conflating anything taking place between the U.S.-Mexico border & Antarctica.

Many of these entertainment-as-propaganda productions include a kind of mea culpa on the part of the United States. In the case of Argo it was a throwaway animated intro sequence depicting the CIA role in the 1953 overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh.

And in Narcos there are indeed some wink-at-camera references to known U.S. wrongdoing, as if absolving them: “We do not get involved in other country’s elections.” insists the Ambassador to the soon-to-be-assassinated justice minister, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla. Meanwhile she admonishes the DEA about “spending US taxpayers money on hookers”. The latter could be taken as a nod to the story which emerged in 2012 as a prostitution scandal, yet developed into a horror involving the abuse by US Agents of at least 54 children in Colombia between 2003-2007.

No subtle references to that made it into the script.

Throw me the idol, I’ll throw you the whip

We should not assume that the Northern Hemisphere’s perception of South America has progressed since 1984’s ‘Romancing the Stone’.

True to form, every ‘South-of-the-border’ cliche, all the attitude-shaping Latin American stereotypes were shoehorned into Narcos. “Can nobody in this country keep a secret?”, our hero Murphy complains.

Then we come to an interesting character who the writers seemed to have some fun with, Carlos Lehder – a Colombian of German descent, in itself not uncommon. Yet Narcos’ creators decided he should bear a massive Swastika tattoo on his arm, and the viewer is left to wonder if this is a sly reference to former SS in Bolivia or a meta take on the ‘Boys from Brazil‘ theme. Just a bit of fun, perhaps…

That’s entertainment

In recent historical/biographical movies such as The Fifth Estate & Imitation Game which dealt with government whistleblowing and encryption respectively, the message to be delivered is not only buried in the screenplay but embedded in the framing. Often there is an editorial template where intended conclusions for the viewer are laid on heavily towards the end of the movie, long-settled in the audience’s perception as a balanced telling of the story.

Unfortunately Narcos is scripted from a default American exceptionalist standpoint and intended for American or American-aligned audiences. The editorial relationship in recent years between government agencies and TV/Movie production has been well documented. It is easy to imagine the majority of viewers taking the show at face value as a – albeit-dramatised – historical document of a part of the world they know little else about.

This is of course part of a wider criticism regarding how the developing world is reported in English. It has to be possible to report, document or dramatise in English from local perspective. It is possible and desirable to tell a story in English without the assumed superiority, the cultural/colonial condescension. “Everyone in this country is a lying, cheating, thieving son-of-a-bitch.”, the Bandito stereotype, the Harlot stereotype, the Latin Lover stereotype and so on.

Sure, a series based on the story of Pablo Escobar might not be the best subject for sober analysis, but in Narcos we have a golden opportunity to do analyse just how bullshit becomes history.

[qpp]