By Gabriel Deslandes.

When the Worker’s Party PT saw itself being pressured like never before by the media coverage of the “mensalão” scandal, its’ leaders probably did not imagine that years later, an investigation of illegal currency exchange operations and capital flight by the Federal Police would end up influencing a campaign of public demoralization of the party and its’ expulsion from the Federal Government. Operation Car Wash revealed an intricate network of corruption, involving overpriced contracts from the country’s biggest contractor companies with Brazilian state oil company Petrobras, and the payment of bribes to politicians of all the major political parties.

Globo’s cameras where once again put in place to depict the chaotic scenery of “institutionalized corruption of the PT administrations”, scripted by the Federal Police and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In fact, the practice of corruption was nothing new in the history of Petrobras, going back to when the Federal Police had less resources and operational autonomy and when governments enjoyed greater sympathy from the big media. What was new after year 2014, when the Car Wash was launched was a climate of public exhaustion with the political class and the juridical tools used to quickly punish the corrupt and corruptors, with plea bargain agreements and precautionary prisons.

Conducting this operation was judge Sérgio Moro and prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, who began to be treated as “anti-corruption crusaders” and became superstars, being invited to various solemnities and award ceremonies, appearing in special media reports and magazine covers. The weapons used by them in the Car Wash operation were similar to those used by Italian magistrates against politicians and businessmen during Operation Mani Pulite in the 90’s. The violation of due legal processes and basic principles, which marked the Italian anti-corruption operation, seems to also have inspired the Car Wash.

Initially, the three main parties involved were the PMDB, PP (a party originated from the basis of the military dictatorship) and the PT. As historian Perry Anderson has said, there where no illusions regarding the first two, but it was the exposure of PT which really gained political relevance. As in the Operation Mani Pulite in Italy, illegal information leaks and even some of the investigator’s suspicions to the press became banalities. The illegal nature of these acts was not sufficient, the leaks also had as a main characteristic the selectivity: the targets were PT’s leaders and members of the Lula and Dilma Rousseff administrations. As for the accusations against the PMDB, they seemed commonplace, and the right-wing parties were spared.

The successive arrests and accusations from the Car Wash coincided with the beginning of the economic recession after Rousseff took office for the second consecutive time. While Lula’s popularity had not been shaken by the repercussion of the mensalão scandal thanks to Brazil’s favorable economic situation and his own political capability, his successor was not as lucky. João Roberto Marinho, vice-president of the Globo Group, requested a personal meeting with Lula in São Paulo in order to ask that he be candidate in the 2014 elections instead of Dilma Rousseff, proving that the communications conglomerate preferred to pragmatically accept a third mandate of Lula as president instead of contemporizing with an unstable second term for Dilma. Despite her reelection, the political and economic crisis created the social ground for the massive protests of conservative sectors of the middle class against the PT, which was now being treated as a “gang of thieves”, and ultimately asking for the ousting of Dilma.

Even though radical right-wing groups articulated the protests through social media, it was Globo who became the main political agent in the mobilization of the middle class in the main cities of Brazil, interrupting its program schedule in order to show live coverage of the protests. The anti-Rousseff protests in 2015 and 2016 counted on intense favorable media coverage, along with an ample team of journalists and commentators emphasizing the “popular pressure against the government”. Globo itself was a fundamental participant in the orientation of what the public opinion should think and feel about the protests.

It was a powerful case of Agenda-setting, a complex symbolic one, with the protesters using the green and yellow colors of the Brazilian flag and nationalistic slogans, while holding up pictures of judge Sérgio Moro and posters celebrating the Operation Car Wash. These symbols transmitted a belief that the protests encompassed national yearnings.

Nonetheless, according to a Datafolha survey on the protests of march of 2016, the majority of protesters in São Paulo where males over 36 years old, half of these had a monthly income between 5 and 20 minimum wages and 77% of them declared themselves to be white. In the 2015 protest, 82% of the protesters said to have voted for Aécio Neves, the opposition candidate who lost the 2014 elections. There was a notorious presence of far right-wing groups asking for “military intervention”, a fact which was downplayed by Globo’s coverage. All of this demonstrates that the majority of the population was underrepresented in the protests.

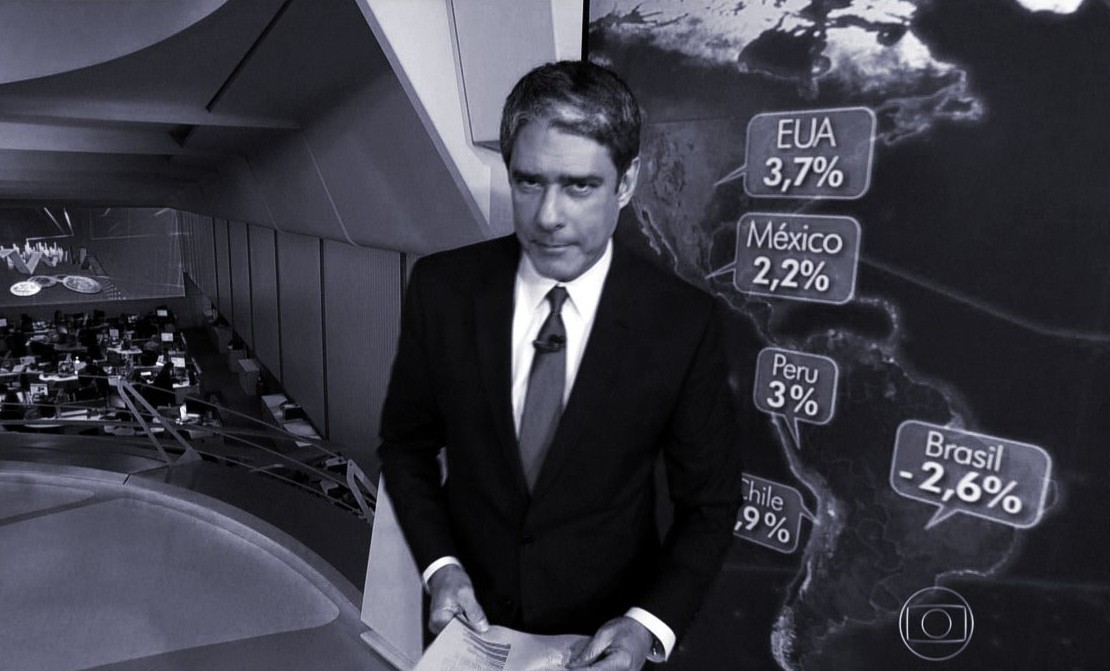

Beyond the political crisis forged by the “fight against corruption”, Globo’s narrative with relation to the recession followed an orthodox reading of the economic problems of Brazil. According to the ideologists of the network, the crisis resulted from Rousseff’s economic policies, in particular the “New Economic Matrix” implemented in 2011. This conventional view suggests that the cutting of taxes and subsidies promoted by the government contributed to the public deficit, the come back of inflation, the withdrawal of confidence and the downfall of investments, pushing the economy into a recession. Following this diagnosis, the Globo Group and the big media in general pointed to a fiscal adjustment in order to “recuperate the confidence of businesses” and “restore confidence in the solvency of the State.

Austerity measures looking for an alleged “rebalancing of public finances” composed a neoliberal prescription that president Dilma Rousseff did not seem willing to apply. Nonetheless, this same prescription was that of document Uma Ponte Para o Futuro (A Bridge to the Future), an economic platform by PMDB which synthesized the regressive reforms later adopted by Michel Temer’s government.

To Globo, it was necessary that the president was taken out of office so that the programmatic agenda would be put into place, even if that meant making alliances in a National Congress composed of congressmen who were investigated or reported due to criminal practices, starting with the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha who was arrested months later by the Operation Car Wash. Of the 367 congressmen who voted favorably for the impeachment, 119 of them already answered for crimes in common or electoral justice or are suspects of involvement in crimes.

Globo and the 2016 coup

Among the main episodes that marked the anti-corruption crusade of the Operation Car Wash, was the disclosing of illegal telephone taps of a conversation between Lula and Rousseff, which was decisive in bringing the impeachment of the president. In the beginning of March of 2016, ex-president Lula was the target of an arbitrary bench warrant by the Federal Police for a judicial interrogatory. The press was notified beforehand, waiting outside his house in order to use their cameras to invade and obtain maximum publicity.

Lula was being investigated because of his relations to contracting companies investigated in the Car Wash. such as Odebrecht and OAS. The operation, authorized by Sérgio Moro, which was in itself a great spectacle, fomented speculations about a possible preventive arrest of the former president. Three days later, Dilma Rousseff nominated him Chief of Staff. As a minister, he would have immunity against Moro’s accusations.

As a revenge, Moro gave Globo recordings of telephone conversations between Lula and Rousseff. The dialogues, which centered around the signature on the necessary documentation for him to take office, were ambiguous. Nonetheless, Globo transformed those audios into a scandal of unimaginable proportions. The spectacle counted with a sensationalist edit by Jornal Nacional, where the anchors read the content of the recordings in order to induce the viewer to conclude that Lula and Rousseff were obstructing the law, from illogical interpretations and the editing of central parts of what Lula said. As a defense, Globo alleged that the “press does produce telephone taps”, and the episode got them a journalism prize in 57th Television Festival in Monte Carlo.

Moro’s act also shows once more how Car Wash’s practices were on the margin of legality. The telephone interception of a conversation of the country’s president was leaked to the press because the judge considered it to be of “public interest”. Nonetheless, the Brazilian Constitution determines that only the Supreme Court can decide about the disclosing of a telephone tap of someone with parliamentary immunity. Beyond that, the telephone dialogue was recorded two hours after the limit of judicial authorization for the recording, stipulated by Moro himself. Not coincidentally, the Supreme Court had to annul the use of these taps as criminal evidence.

Regardless of this selective character against PT by the investigations so far, the political class was conscious of the reach of these corruption cases involving the contractor companies and Petrobras. Even after promising to not interfere with the Car Wash, Michel Temer – who himself had been mentioned in plea bargains – nominated seven investigated politicians in the operation to compose his ministerial team, which had already become a daily soap opera. It became clear that it was a question of time and good will for the investigations to reach the new government and Temer’s party, PMDB.

The Globo Group finds itself in a double function by supporting the political and economic platform of Temer and, simultaneously, a police operation which could reach the leaders of the new government. According to journalist Luis Nassif, the initial message the newsrooms sent to their employees was that of not attacking Temer’s chosen ministers. Nonetheless, days after Temer took office, the same press published a recording of the new minister Romero Jucá affirming his interest to “stop the bleeding”, which meant using the government to stop the Car Wash investigations.

The Car Wash Party and the destruction of politics

The compromise with neoliberal reforms seems not to have prevented Globo to recognize popular rejection to the new president. In July 2016, the first Ibope survey after Temer took office showed that only 13% of Brazilians approved of his government. According to the last Datafolha survey, National Congress reached the record of 60% popular disapproval. For political scientist Lucas Cunha, researcher at the Center for Legislative Studies at UFMG university, this negative perception of the Brazilian population points to the risk of total discredit of the institutions and to the resolution of the political system’s problems by forces outside of politics.

In this context, the task force of the Car Wash incarnates the popular appeal to the “State clean-up” in the name of ethics, and the editorial directives from Globo, the biggest beneficiary of the selective leaks of the investigation, gave support to the pressure being put onto the Federal Police and judges of first instance against the Executive and Legislative powers. Conscious of the potential of this alliance with the great media, shown on the non-critical coverage of the Car Wash operation, judges, prosecutors have been using a hyper concentrated institutional power capable of neutralizing the actions of the political class, stigmatizing the role of the State and hampering the country’s governability.

During the spectacle like coverage of Globo, dissonant voices to the judicial activism led by the operation were practically non-existent. The big media was transformed into a monopoly of public opinion, while helping to promote magistrates, prosecutors and police agents to the status of heroes. This “penal mediatization” is capable of simultaneously following and integrating the “fight against corruption” .The criminalization of a conduct or the persecution of a specific individual or group ended up being completely conditioned by the media’s agenda, which, in judge Moro’s own view, must occupy a central role in the operations.

The “ends justify the means” logic, promoted by the Judiciary and the Public Prosecutor’s Office through the punishment at any cost of those being investigated by the Car Wash, has been overriding constitutional rights in cases of abuse of preventive arrests, violations of the right of defense and in judge’s interference in plea bargain agreements. Ethical and legal standards are violated, creating space for authoritarianism. The peak of this movement was the aberrant “10 measures against corruption” proposal, presented as a law project by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. This series of measures included flagrant violations to the Democratic Rule of Law, with limitations concerning Habeas Corpus, the admission of illicit evidence by courts and even “integrity tests” to evaluate moral conduct of public employees.

On November 30th of 2016, the “10 measures against corruption” package was voted in National Congress, and deputes approved several changes in the text, altering the Prosecutor’s Office’s project completely. The prosecutors of the Car Wash task force were quick in accusing the Chamber of Deputies of trying to install a “corruption dictatorship” and threatened to abandon the investigations. The GloboNews broadcast and the newspaper O Globo gave ample coverage not only to the voting of the project, which they called the “disfiguration of the anticorruption package” and “constraint of Justice’s actions”, but also to the Public Prosecutor’s Office’s reaction.

Therefore, this episode makes clear that, in a choice between an alliance with the conservative sectors of a discredited political class or with the judicial-media activism of Operation Car Wash, Globo Group preferred the second option. With the Worker’s Party already out of the political game, the selective nature of the investigations gradually decreased, and the traditional right-wing political parties could no longer exploit the narrative of the “indignation against corruption” promoted by the police operation. Even prosecutor Carlos Fernando dos Santos Lima confessed that many politicians who previously supported investigations against PT “only wanted the end of the Rousseff’s government and not the end of corruption.”

By pressuring the Legislative Power to approve a law project, federal prosecutors are abdicating their position of institutional neutrality stated by the Constitution and creating an organized political movement. In this aspect, the Car Wash task force becomes a de facto political party. with strong support from the big media. It was through this partnership that the Globo Group gave gigantic coverage, in April 2017, to the videos of the plea bargain agreement talks of the owners and executives of Odebrecht construction company, whose depositions reached the main characters of all major political parties.

With all parties being involved in scandals right in front of the population’s eyes, in May 2017, Globo took the liberty to dismiss Michel Temer when publishing the biggest political bomb of the year: the compromising talks between the president and business man Joesley Batista, owner of JBS meat processing company. Two days after the scandal when both negotiated buying the silence of Eduardo Cunha”, the newspaper O Globo published an editorial entitled “The president’s renunciation”, alleging that Temer “lost the moral, ethic, political and administrative conditions to keep governing Brazil”.

As it is well known, Temer not only did not renounce the presidency, but was also able to defeat two investigation requests for crimes of criminal organization and obstruction of Justice, presented by the attorney-general Rodrigo Janot. Nonetheless, Temer’s permanence in office helped turn him in the most unpopular president in the history of Brazil, with mere 3% public approval, and to mine even further the credibility of the National Congress to the public. The president, as a counter attack to the same network which helped put him in power, decided to declare war on Globo. Temer ordered the execution of eventual debts of the network with the Union, as well as taxes and loans from the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES).

The “judicialization of politics” and the repetition ad nauseam of the term “corruption” promoted by the Globo-Car Wash partnership, created a climate of waste land in Brazil. With all the demoralization of the Presidency of the Republic and of the great political parties of all ideologies, the network seems to have bet on a new political ordainment which keeps the status quo operating neoliberal reforms, but without the continuous symbolic association of economic policy to the corrupt image of Temer and his political basis in the National Congress. In Globo’s view, it was indispensable that the Federal Government implements labor and pension reforms, the new framework for exploration of pre-salt oil fields and the freezing of public spending. However, the leadership of a unpopular president guiding these reforms was disposable and even undesirable.

On the other side, by adhering to fiscal austerity and the cutting of social rights, Globo not only has found difficulty in appeasing popular discontent with economic and distributive problems in Brazil, but it may also be involuntarily catalyzing this discontent against itself. Sociologist Jessé Souza says the years of selective attacks to the Worker’s Party, a party which until this day is identified as a symbol of social equality in the collective imagination, may have opened the gates to discourses favoring the criminalization of social justice and to the destruction of democratic values: the far right-wing.

[qpp]