Carlos Latuff is one of the World’s most famous political cartoonists. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1968, he published his first political cartoon in a Longshoremen’s Union newspaper in 1989 and continues drawing cartoons for unions to this day. As the internet gained force during the 1990s, he began drawing cartoons in solidarity with the Zapatistas, the IRA, Palestinian refugees and other leftist causes around the World. During the Arab spring of 2011, he began publishing daily cartoons on middle eastern politics and developed a world wide following. In August, 2017, Al Jazeera interviewed Latuff for a recent Al Jazeera’ episode of the Listening Post called Brazil: Media, Monopolies and Political Manipulation about the media’s role in the 2016 coup. I worked as a producer on the project and they were kind enough to share the entire interview with Brasil Wire. The following is an edited version of those those transcripts.

– Brian Mier

Some people say Brasil is suffering from its worst crisis in decades. How has the media responded to this?

Brazil is going through a crisis but I don’t think it’s anything new. Brazil’s history is full of crises, so I don’t think this is the biggest crisis ever. The coverage, from either the mainstream media or independent-alternative would be more accurate – organisations means people learn more about what’s happening via social media. The coverage of the crisis by the Brazilian press has been very biased, which doesn’t surprise me because there’s no such thing as independent journalism. Journalism always takes a side, whether the journalist chooses to admit it or not.

What do you think is the cause of the crisis?

Brazil is an oligarchical country. It’s a country controlled by a small number of rich families. In fact, the Brazilian press is controlled by rich families. Brazil’s history is full of crises and the current crisis is the result of an internal struggle among sectors of the oligarchy. Dilma’s impeachment opened a Pandora’s box.

A recent report by Reporters Without Borders calls Brazil the “Country of 30 Berlusconnis”. Do you think this is an accurate depiction?

Yes, Brazil is definitely a country full of Berlusconis, right? In my opinion it’s a legacy from Portuguese colonialism. There’s nothing about colonialism that should be celebrated. The famous Brazilian jeitinho came about out of necessity, a way of the Brazilian population resisting the colonialists. Except that later on it became a Brazilian way of life. And we’ll take it as far as we can. This jeitinho pops up from politics at the very top down to interpersonal relationships on the street. The Brazilian media is controlled by traditional families so it obviously follows the same principles as the old regency. The only reason Temer hasn’t fallen yet is because of their internal struggle. Globo asked for Temer’s head on a plate, that’s big stuff. Globo helped take down João Goulart and it helped take down Collor. It took down Dilma and asked for Temer’s head on a plate. He’s only still in government because a sector of the oligarchy, as I mentioned, is keeping Temer there so he can approve the workers’ rights and pension reforms quickly. They want this done in a hurry. That means Temer’s expiration date is coming up. The press is tied to the banks and the financial markets and it wants these reforms to be approved. If you turn on the TV here practically all of the networks and all of the news anchors support the reforms. The press has a side. The mainstream media’s side is money- it’s the same side as the financial markets. Since the Brazilian press is controlled by wealthy families, it’s also part of the anachronistic oligarchy that still governs Brazil.

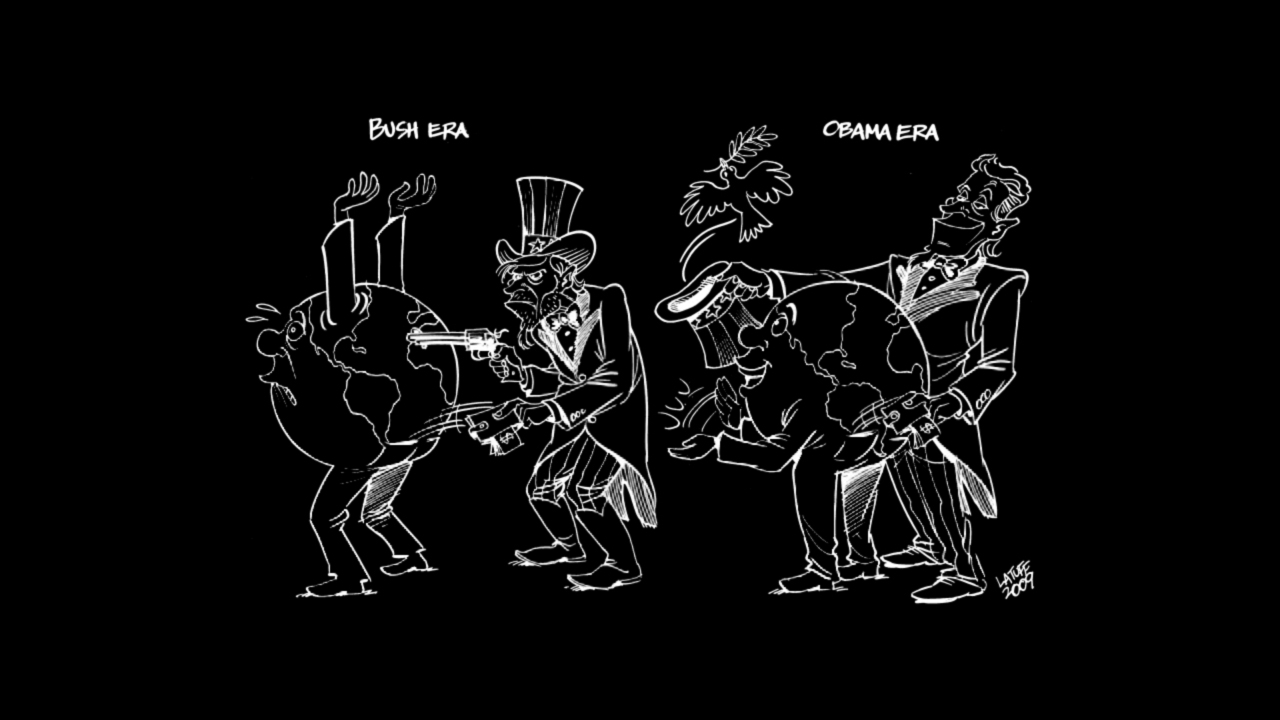

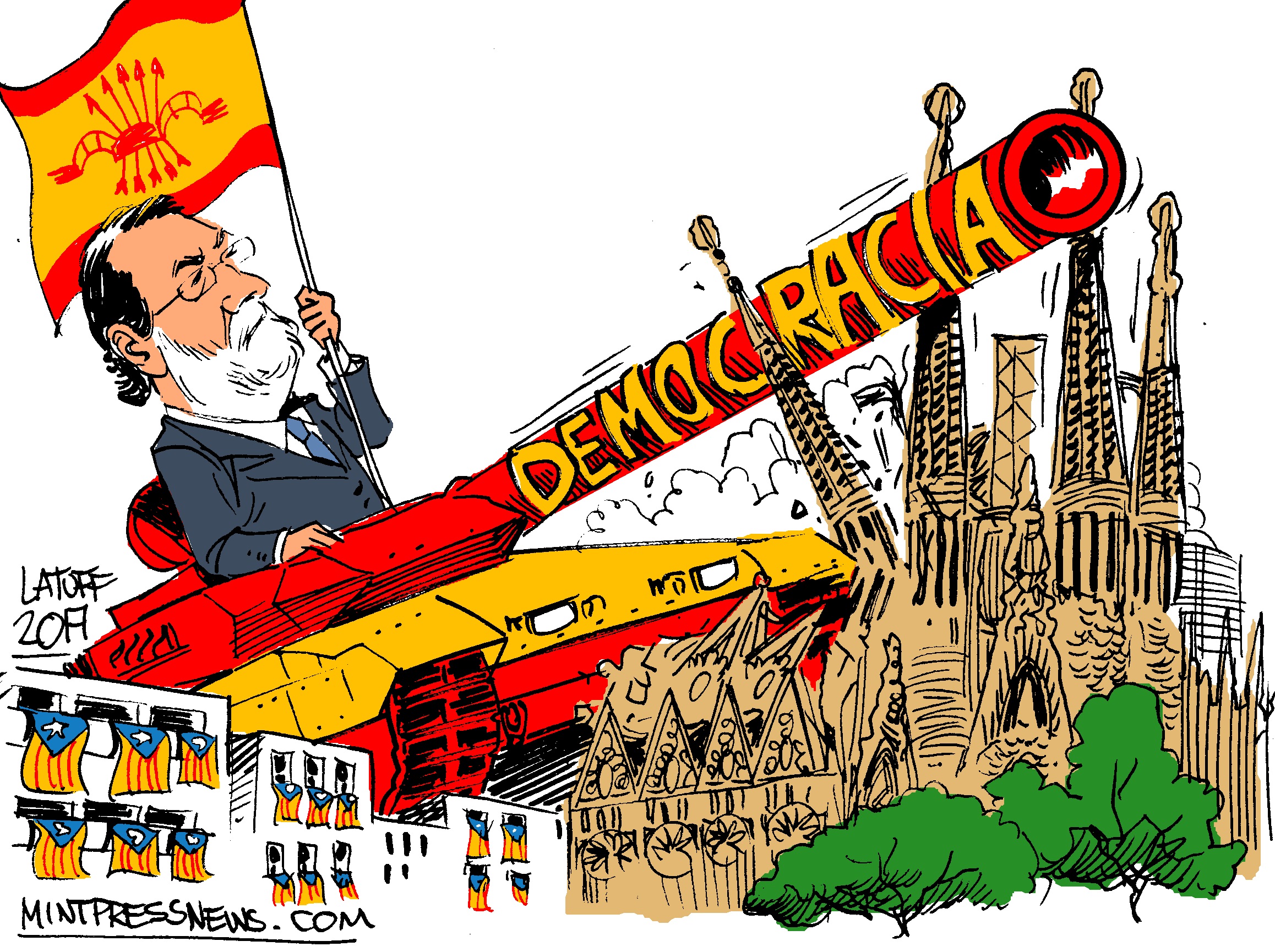

Can you talk a bit about your Cartoons?

My cartoons are often used by the leftist press. But nowadays, with the advent of social media, it hasn’t only been the left media using them but the average person too, with similar opinions. It is no longer necessarily a union member or a leftist militant. The range of people who access and reproduce my work has really opened up thanks to the Internet. Throughout my my career – which began in 1990 right when the press became unionized – the themes have generally been social-political issues: police brutality, state terrorism, corruption, political maneuvers. There a saying amongst cartoonists here in Brazil that goes,“there’s no such thing as a positive cartoon.” There aren’t cartoons that support things. The themes are always difficult. And not just in Brazil, the themes I tackle looking abroad include war, armed conflicts, and torture. I’ve also done a lot about the Brazilian military dictatorship. I’m not from that era- I was born in ’68. But I’ve done a lot of work about the dictatorship, about missing persons and human rights violations. I decided to draw this cartoon about the Partida da Imprensa Golpista (the Press Coup Party). I didn’t actually come up with that term. This term is credited to a journalist named Paulo Henrique Amorim. He’s the first person I remember using it. So I drew a pig even though I love pigs. I drew a pig in white-collar and tie, sitting in a tank, alluding to the military coup. The tank’s gun is a rolled-up newspaper coming out of a television. In other words, you’ve got the printed, written press and the TV. The Brazilian press, more specifically TV Globo, have been responsible for taking down presidents. So that’s why I made this drawing, to represent this so-called pro-coup press party, which is the mainstream media. They have the ability to take down or put presidents in place. This expression, PIG, has long been coined by the left and is especially used by PT supporters. But when the PT was in government it could have done more. It could have taken steps to stop this monopoly, to put an end to the media oligarchy that is tied to the wealthiest families in Brazil. Instead of Lula or Dilma’s government effectively supporting the alternative leftist press- let’s say, for example, Brasil de Fato which is a newspaper tied to the MST – they chose to support the pro-coup press. When the Folha de São Paulo celebrated its anniversary Dilma went there to personally congratulate them. She made a speech and hugged Otavinho Frias who owns the newspaper. That’s the problem. If you’re against the pro-coup press but also support them, it’s contradictory, right? I think that during the Lula and Dilma governments it would’ve been possible to at least start taking some kind of action against the oligarchy that controls communications networks in Brazil. But this didn’t happen.

Can you give another example of Brazilian press influence in politics?

Why is it that Globo is interested in retirement pension reforms? Ever since I can remember, even during Fernando Hernique Cardoso’s term, Globo has always defended these reforms, especially the pension reforms, saying that the pension system was crumbling and that it needs to be reformed. Behind all of this is the banks’ interest in selling private retirement plans. So the banks and the TV network are working together. They have a common interest, they have shared interests. That’s why you see so many news reports and TV editorials supporting the pension reforms. The bank can’t speak for itself, the bank doesn’t have a TV channel. You don’t see the banker speaking but he has people speaking for him. And that’s what TV does. The banker doesn’t have to expose himself, he stays behind his desk while the pro-coup press defends his interests.

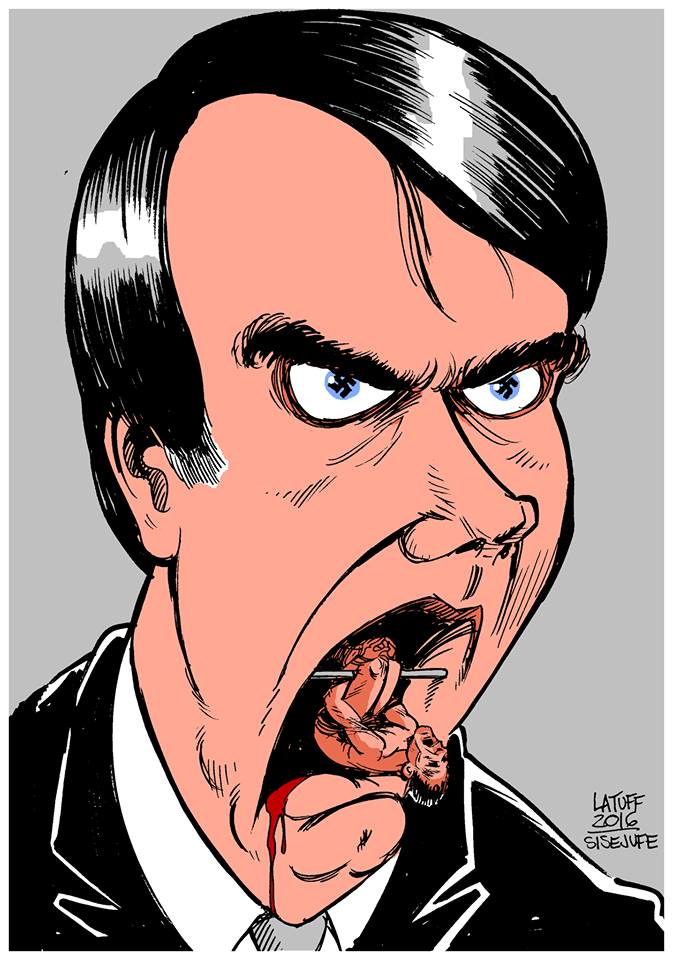

Can you explain this cartoon?

This cartoon was made during Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment process. It was an irregular procedure disguised in a veneer of legality by way of a procedure that went through congress. There was an impeachment vote against Dilma. Each congressman openly declared his vote. You saw all of these politicians, infamous hoodlums, saying, “I vote in favor of Dilma’s impeachment for my family, for God, for my children.” And some of them, most of them in fact, were facing legal processes. They are connected to corruption schemes but were there declaring the most noble reasons to impeach Dilma. The process was utterly embarrassing. That’s exactly what the cartoon shows. We showed the World that we truly are a banana republic. I’m in contact with the whole world. I draw about the whole world, about problems from around the world. I understand that corruption is a problem that affects every country and I’ll go as far as to say that, from a philosophical point of view, corruption is part of the human condition. I understand that completely. But that impeachment voting scene that was embarrassing. I truly felt ashamed of being Brazilian.

This cartoon shows a small farmer from the MST attacked by four powers: the police, agribusiness, the judiciary, and the press. As I said before, Brazil is an oligarchy, it’s a country living in a bygone era. But the way in which the oligarchy exerts social control is through these forces. This control has always existed in Brazil. Brazil is not a peaceful country like they want you to think. The problem is not just urban violence. Brazil’s history is full of revolutions, insurrections and people’s revolts. All of them were crushed by the state. The state is very efficient at repressing, silencing and crushing popular revolts. If you have a country controlled by the regency, it’s obvious that at some point you’ll have people rising up against it. But what they normally say, despite all the revolts, is that Brazil’s independence from Portugal consisted of a man on a horse with a sword. The transition from empire to republic was just a sword in the hand without a shot fired. Slavery was ended with the stroke of a pen. The new state was declared by Getúlio Vargas by tying a horse to the obelisk on Rio Branco Avenue here in downtown Rio de Janeiro. The 1964 coup took place without a shot fired. So what do we learn from these things? We learn that over here, the establishment, the dominant class, knows when crises will happen. They can’t stop a crisis from happening but when it does they act quickly to neutralise it before it erupts because once it does there’s no controlling it. They risk losing power. In Brazil, everything is always decided from above. How does the oligarchy control things? With these tools. They passed an anti-terrorism law here in Brazil and it’s only a matter of time before they use it to confront the MST and the Movimento de Trabalhadores Sem Teto(Homeless Workers Movement/MTST). That’s what happens nowadays- we continue to have cyclical crises. Brazil’s history is just one crisis after another. Now we have this issue of corruption whistle-blowing. In my opinion, the population is asleep. It’s in a coma. They turn on the TV and all they see are scandals, but there are no alternatives. The only alternatives they have are even worse. Which tools does the establishment use today to crush popular revolt? They use TV, soap operas and carnival. It’s all an attempt to keep you in a coma in front of the TV. If you’re not dormant, if you take the red pill, you’ll start taking to the streets. And when you take to the streets, the TV no longer has power over you, so it’s the turn of the police and the judiciary.

It’s just a matter of time in Brazil before they start labeling the social movements as terrorists. They’re already rehearsing this. The law was approved during Dilma’s government- she was a victim of state terrorism herself but she approved this law so it went through. My cartoons show the tools the oligarchy uses for social control. The first tool is this: religion, entertainment, the soap operas, football and carnival. Think about this: the football hooligans fight to the death in stadiums. They have an anger deep inside them. People have this anger but they don’t know how to direct it at the right people so they kill each other. I think that the biggest myth of all is that of the friendly Brazilian, the cordial man, Brazil as a cordial country. When you establish that the average Brazilian is friendly, you then have this argument that there’s no racism because everyone is friendly. No one is homophobic, no one is racist. In Brazil everything’s too friendly. No one considers themselves racist and you can’t confront something you don’t actually see. The USA had a policy of apartheid, segregation, whites only. There was nothing like this in Brazil. Maybe we needed signs. You’d have to come out and say it here for people to realise it existed. That’s why the dominant class in Brazil is so good at keeping us in these terrible conditions that we live in. That’s why they’ve always been so efficient at silencing dissident voices in Brazil. They mask the truth, they mask the fact that Brazil is a banana republic, a colony, a racist country. But since we don’t have “whites only” signs on the bus bench, in the bathrooms – anywhere – we created this myth of the friendly Brazilian. It’s all fake. A country that had slavery can’t say it’s not racist. Even today you can go to certain colonial houses that still have quarters where slaves used to live, torture instruments and slave prison cells. A place with that kind of history can’t say it’s not racist.

[qpp]