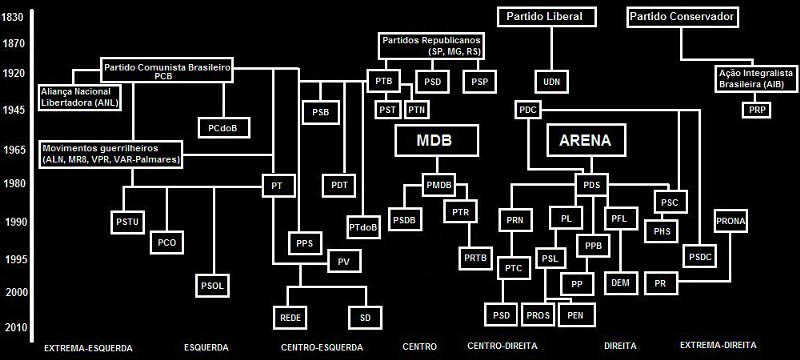

Source: A árvore genealógica dos partidos políticos do Brasil by Felipe Duarte.

Who hasn’t been curious to draw a family tree? Especially if you’re from a family of immigrants (German, Italian, etc.) You know that hint of curiosity, which leads you to think, ‘where do I come from and where am I going?’ Well these past days I decided to dwell a bit on the history of Brazilian political parties and do the same. As I’m not a historian nor political scientist, the design might have some faults. Nevertheless, it helped me organise my ideas and better recognise in which terrain and context certain current political parties fit. If in doubt, check the table above.

Imperial Brazil and Old Republic

To start off, in Imperial Brazil (1822–1889), two parties ‘of the right’ that defended the maintenance of slavery shared power: the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party. The scenario only began to change with the appearance of the Republican Parties. There was no national union at the time, with cadres being formed within the states (the Republic Parties of São Paulo, of Minas Gerais, of Rio Grande do Sul — of Júlio de Castilhos, for example). These mainly dominated the stage as of the Proclamation of the Republic and established the ‘coffee with milk’ politics, with paulistas and mineiros alternating power. It’s important to understand than in this period there was no universal suffrage, which is to say, women were denied the vote. Therefore, political figures were those of the social elite.

Vargas Era

Emerging from the PRR (Republican Party of Rio Grande do Sul), thegaúcho Getúlio Vargas took the presidency in 1930 thanks to a coup d’état which interrupted the paulista and mineiro rotation of power. Four years later, he promulgated a new Constitution, imposing amongst others the secret vote, the female suffrage and workers’ rights. With the implantation of the Estado Novo (‘New State’ — nothing more than a populist dictatorship), we saw the opposition radicalising itself between extreme-right and extreme-left: the Ação Integralista Brasileira (AIB, Brazilian Integralist Action), which advocated for a fascist government; and the Aliança Nacional Libertadora (ANL, National Liberation Alliance) formed by members of the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party). Incidentally, the latter, knows as the ‘Big Party’ was the first entry of the left into national politics, founded back in 1922, and ended up being made illegal by many of the governments that took charge of the country.

Despite powerful rebellions organised by these two fronts, Vargas kept control of the presidency until 1945. He would return via election five years later, but before that he became the guarantor of two parties which would be founded: PSD (Social Democratic Party) and PTB (Brazilian Labour Party) — which he joined. On the other end of the spectrum emerged the UDN (National Democratic Union), a descendent of the Liberal and Conservative Parties. This would be the main opposition to the getulistagovernment until Vargas’ suicide in 1954.

Military Dictatorship

With the military coup in 1964, supported initially by the UDN to bring down the labour government of João Goulart (‘political son’ to Vargas), all the parties — from left to right — became illegal: from the PCdoB (Communist Party of Brazil, descendent of the PCB — Brazilian Communist Party), passing by the PSB (Brazilian Socialist Party, a meeting of the ideologies of the PCB and the PTB), to the PDC (Christian Democratic Party), and affecting even the UDN itself. Only two parties were permitted: MDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement) and ARENA (National Renewal Alliance) It was as if, from one moment to the next, national politics had returned to the Imperial period, where only the liberals and conservatives were active. The cadres of the centre-left went into exile (like the PTB’s Leonel Brioza), while those of the extreme-left embraced illegality and created armed groups — ALN (National Liberation Alliance), MR8 (Revolutionary Movement of 8 October) VPR (Popular Revolutionary Vanguard), amongst others.

Political Reopening

Out of the popular demonstrations for the end of military government emerged new parties. With getulista DNA, Brizola founded the PDT (Democratic Labour Party). It even received some components of revolutionary groups, though the majority ended up migrating to the recently-founded PT (Workers Party), where they joined up with labour movements. Out of the disrepute of ARENA emerged the PDS (Social Democratic Party), which would harbour politicians who previously governed under the military umbrella, like José Sarney. The MDB, for its part, was the party which surfed the wave of political opening, becoming the face of the new Brazilian democracy. Old parties, like the Cob, PSB and PTB, were also reactivated, but having discarded their founding ideologies.

Coalitions and ‘physiologism’

As of the 90s, parties began to multiply. From the right came the PDS and PFL (Liberal Front Party, which today is DEM, or Democratas), PPB (Brazilian Progressive Party, today just PP), and PRN (Party of National Reconstruction, today PTC) — which would elect Fernando Collor in the first direct elections. Out of the gigantic PMDB emerged principally the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democratic Party). Various strands of radical left migrated out of the PT, such as the PSTU (United Workers Socialist Party), PCO (Workers’ Cause Party) and more recently PSOL (Party of Socialism and Liberty).

Collor’s impeachment in 1992, however, would significantly influence the physiologism in Brazilian democratic life. The constant swapping of parties — like the vice-president at the time, Itamar Franco, who would be on his fifth party by the time he gained the presidency (PTB, MDB, PL, PRN and PMDB) — reflected badly on the lack of loyalty to ideological roots.

As well as this, the system of ‘coalition presidentialism’ breathed into life previously unthinkable coalitions. The ‘toucan’ Fernando Henrique Cardoso, for example, ex-MDB, allied with the PFL (dissidents from the PDS and ARENA) to win the 1994 and 1998 elections. The petista Lula united with the PL to do likewise in 2002 and 2006. Did the liberals of Imperial Brazil ever imagine that their political heirs would one day join forces with workers from the union movement? From this improbable coalition, for example, emerged the contemporary SD (Solidarity) whose president is the federal deputy Paulinho da Força Sindical (‘Union Force’) — an ex-petista, who became one of the main bases of support for the recent impeachment of Dilma Rousseff.

Another creation of physiologism is the recently created Sustainability Network, which manages to shelter its founder Marina Silva, ex-PT and PV (Green party); Randolfe Rodrigues, ex-PSOL; Miro Teixeira, ex-PP, PDT and PROS (Republica Party of Social Order); e João Derly, ex-PCdoB. And this is without even mentioning the PSC (Social Christian Party), heir of the old PDC which was dissolved by the military dictatorship, but which has now launched the pre-candidacy of Jair Bolsonaro, a military regime enthusiast. But perhaps the biggest ‘bastard son’ of Brazilian politics is the PR (Party of the Republic), born of a fusion between PL and PRONA (Reconstruction of National Order Party) – dreamt up and created by the ultranationalist Enéas Carneiro, a distant cousin of the integralist [fascist] Plínio Salgado. Even so, this didn’t stop it from entering into coalition with the PT for Dilma’s election.

Given the situation, in which no one knows any more who is their friend or enemy in this treachery, reform of Brazilian politics is urgent. Or you can continue to savour this promiscuous and indigestible alphabet soup.

[qpp]