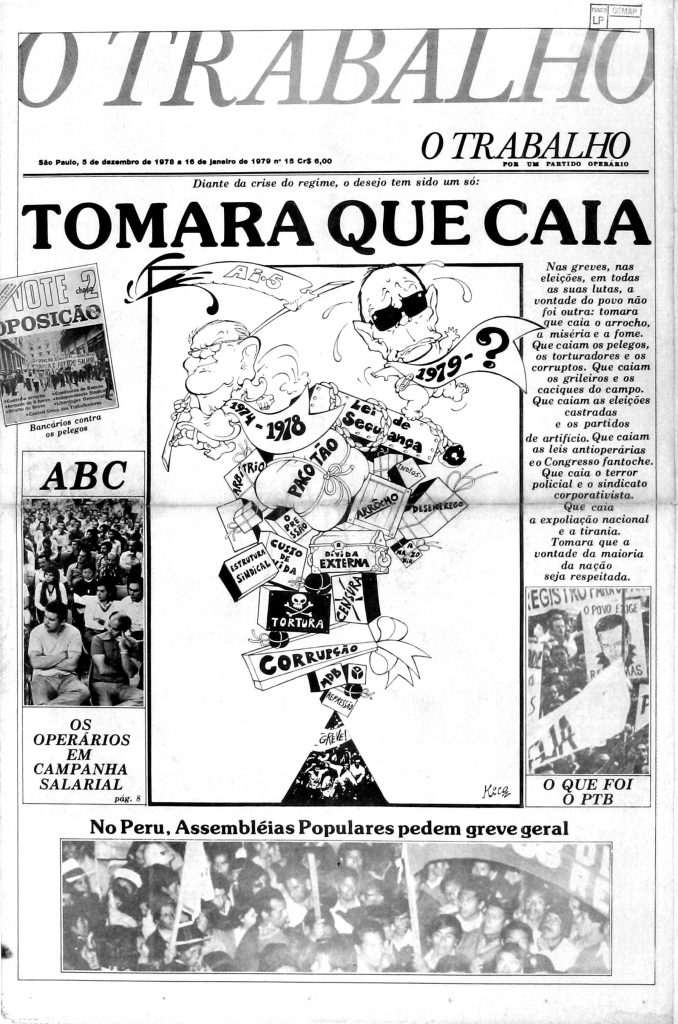

On May 1, 1978, the first issue of the Brazilian underground newspaper O Trabalho hit the streets. The paper was the result of the fusion of 4 clandestine Trotskyist organizations with the student movement Libelu, all outlawed by the authoritarian military junta at the time. In this article, Paulo Moreira Leite, founding editor of O Trabalho and one of Brazil’s most accomplished journalists, looks back at a moment in history when hundreds of fragmented and persecuted leftist organizations joined together with the labor unions to fight the US-backed dictatorship.

by Paulo Moreira Leite*

Like so many people throughout history, I spent much of my youth trying to make sense of what was going on in my country, Brazil. Then history hit me in the face. It changed my existence and the plans of many in my generation.

In 1973 I enrolled in the Universidade de São Paulo, a free, public institution that is a source of pride for us Brazilians. Even today, it’s ranked among the World’s Top 100 Universities. I wanted to be an intellectual and produce academic research, but I ran out of time and was forced to drop out when my generation got caught in a whirlwind of political and social changes that transformed ourselves and Brazil forever.

During the first few weeks of class, the military junta’s DOI CODI political police arrested, tortured, and executed Alexandre Vannuchi Leme, a geology student and member of the ALN armed revolutionary group founded by Carlos Marighella, one of the main leaders of the Brazilian left during the 20th century. In a large-scale police operation in 1974, the government arrested 18 students and teachers in a university preparatory course and submitted them to prolonged sessions of torture. In 1975, an action against the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party) ended with the execution of many of its directors and most important members. In 1976, the entire directorate of the PC do B (Communist Party of Brazil) was machine gunned down during a central committee meeting. In 1977, the arrest and torture of activists from the Trotskiest Workers League provoked a large protest in downtown São Paulo, the first time in years that the student movement came out to the streets to confront the military police and denounce the cowardliness of the regime.

Despite the open violence and permanent threats from the generals, many people worked together to fight for structural change. Here is a personal example. Among my cohorts in the social sciences department there were activists from the Catholic left associated with the liberation theology movement, members of two orthodox communist parties and two Trotskiest groups, former armed guerrillas, and at least one group of self-proclaimed independents, who the rest of us criticized as excessively moderate reformists.

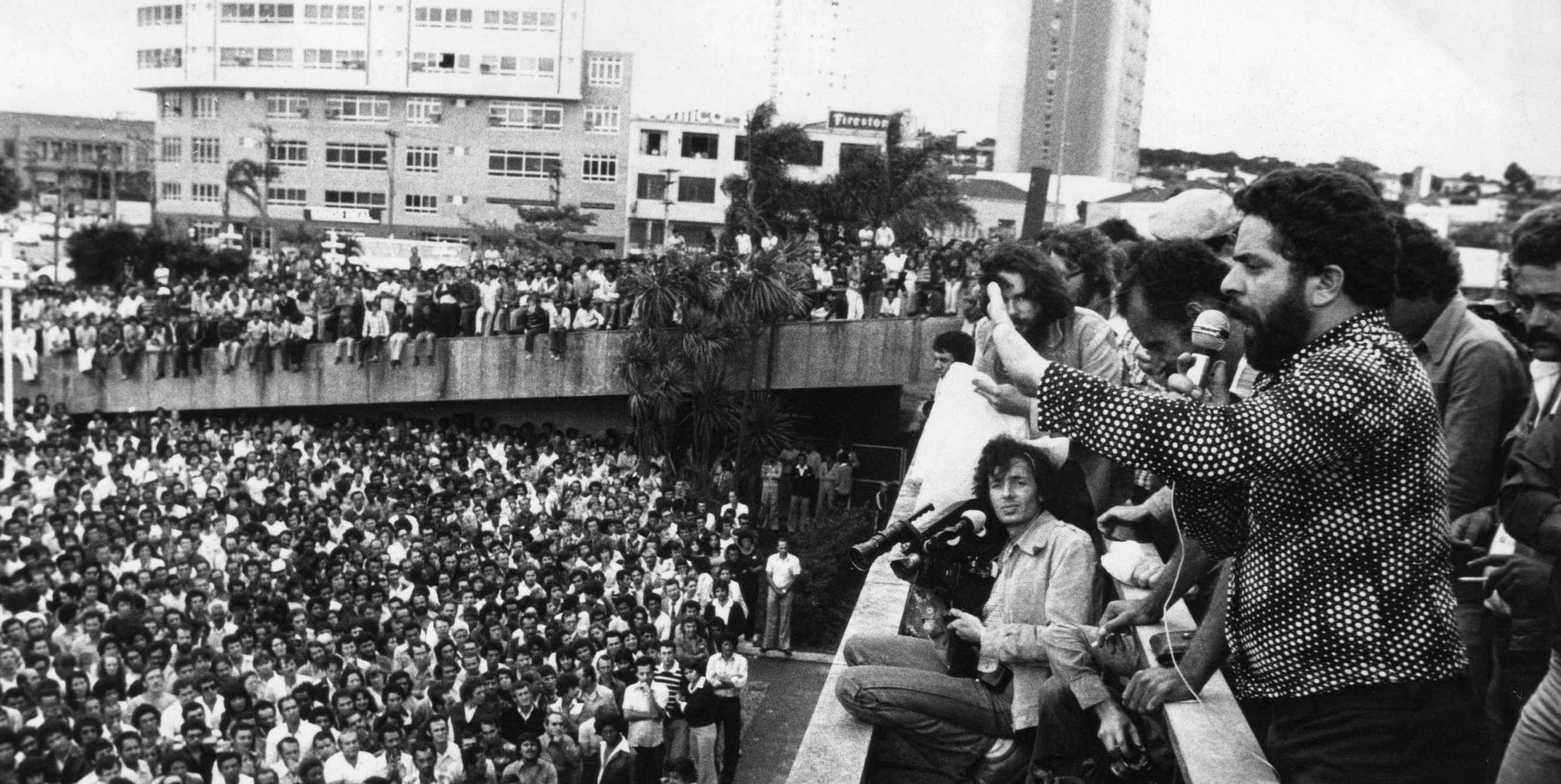

There were always a lot of good laughs to be had among such a varied group, especially since it seemed so futile, at least in appearances, to take on a dictatorship that was born and sustained by the most powerful force on the planet: the North American Empire. But you couldn’t ignore the fact that among that miscellaneous collection of revolutionary groups with different acronyms there was, above everything else, an immense will to defeat the dictatorship and change Brazil. This became even more clear in 1978, when a force emerged that, from that point forward, would make a huge difference for the majority of the Brazilian people. Under the leadership of Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, the labor union movement would become a decisive force in Brazilian politics for the next five decades.

Starting with a series of wildcat strikes and work stoppages that triggered the end of a regime that was planning to stay in power forever, the union workers exposed a system of super-exploitation that was one of the government’s pillars of order. This exposure of class conflict set the tone for all street protests from that moment forward, as the fight against capitalist exploitation became an important and often mandatory rallying cry. A military regime, that was born out of wage stagnation enforced by tanks and bayonets, began to tremble in its boots when the workers held nationwide strikes to protest against the counterfeit inflationary indices used to mask the erosion of their paychecks.

In 1978, the first issues of the illegal, underground newspaper O Trabalho (Work) hit the streets.

During the 1960s, a lot of middle class kids joined the armed struggle, and many of them lost their lives, criminally sacrificed to the machine. A decade later, resistance to the dictatorship took the form of labor struggle, and we soon discovered that this changed everything. Student activists began to go to assemblies and take up collections to deliver money and food to the families of striking workers. In an unforgettable symbolic gesture, I remember the day one young writer friend showed up with a 5 pound salmon for striking steelworkers.

This coalition of forces, born out of the working class base of Brazilian society, led to the four consecutive presidencies of Lula and Dilma Rousseff, the two most popular leaders in the history of our Republic. This movement led to essential improvements to our development and sovereignty, and for the well being of the poorest segments of society. One example is how enrollment in the free public universities expanded, with 52% of spaces reserved for poor and Afro-Brazilian students.

As we recover from the embarrassing attack against our democracy in 2016, when Dilma Rousseff was deposed through a coup d’ etat, Brazil is beginning to reopen its doors to a better future that will do justice to its economy, natural resources, and culture and make up for the last five years of lost time. Like many lessons that old age can teach the youth, the massive level of support that our population is showing for Lula right now shows that the consciousness of our country hasn’t been lost.

*Paulo Moreira Leite started his career as a reporter in 1969 and has worked at Brazilian news publications such as Gazeta Mercantil, Folha de São Paulo, Veja and Istoé. He is currently Editor of Brasil 247.

This article was originally commissioned and translated by Brian Mier for the Chicago-based, print magazine Lumpen.

[qpp]