No country’s history, society, or politics is defined merely by its (male) political leaders. During the dictatorship, millions of Brazilians resisted the military’s authority (even while millions more supported it), and support and/or opposition from various social groups ebbed and flowed throughout twenty-one years of military rule. While there is no shortage of materials on resistance to the dictatorship, especially in the 1960s, such work tends to focus on the men (often university students) who challenged the regime (and who later went on to play roles in the post-dictatorship state), even while women played key roles in the student movements that challenged military rule in a number of ways. Thus, we begin looking at the lives of these women, often ignored in the narrative of resistance to the dictatorship, by focusing on one of the most important yet most overlooked figures of student politics and resistance in the 1960s: Vera Sílvia Magalhães.

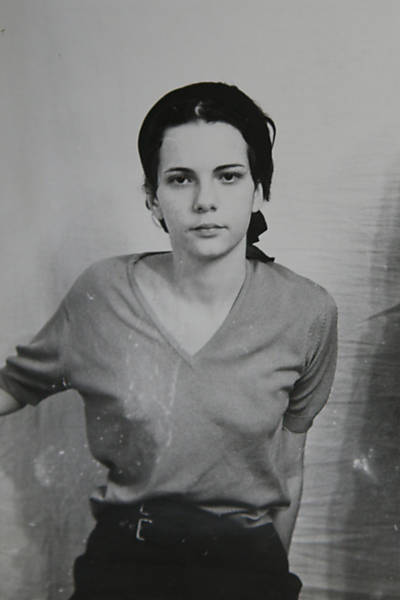

Vera Sílvia Magalhães was born to a middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro in 1948. Although her family was from the carioca upper middle class, they did not shy away from communism; she allegedly first read Marx and Engels after a family member gave her the Communist Manifesto. Although apocryphal, what is certain is that, from an early age, she was exposed to the ideas of the left, and by the age of 15, she was a member of the Associação Municipal dos Estudantes Secundaristas (Municipal Association of Secondary Students; AMES). One year after she joined AMES, the military overthrew constitutional president João Goulart in a coup, ushering in a right-wing military regime.

Although president Humberto Castelo Branco’s government had made early attempts to crack down on the student movements in Brazil, they were not as thorough or persistent as efforts to persecute labor activists, high-ranking politicians, or members of Brazil’s Leninist Partido Comunista Brasileiro (Brazilian Communist Party; PCB). Thus, less than two years after the coup, university students had become one of the main groups still openly challenging the military dictatorship, criticizing it both along ideological lines while also making more quotidian demands that reflected their experiences as middle-class university students. While some students participated in protests through the “semi-clandestine” National Students Union (UNE), by 1967, other students were becoming more radical. Discontent with the failures of the PCB to adequately address the “Brazilian reality” and frustrated by the fact that, far from ending the dictatorship, street protests only seemed to lead to intensifying police violence under president Artur Costa e Silva, some leftist students looked for more radical solutions to transform Brazilian politics and society. Yet the older members of the PCB, Brazil’s first communist party, refused to endorse the armed struggle as a path towards social change and the end of the dictatorship. As a result, university students turned to alternate offshoot groups. Drawing on the model of the Cuban revolution and abandoning the “Old left” of Leninism for Maoist and/or “Dissident” versions of communism, a small number of urban youth began to see the luta armada, or armed struggle, as the only path to bring down the dictatorship.

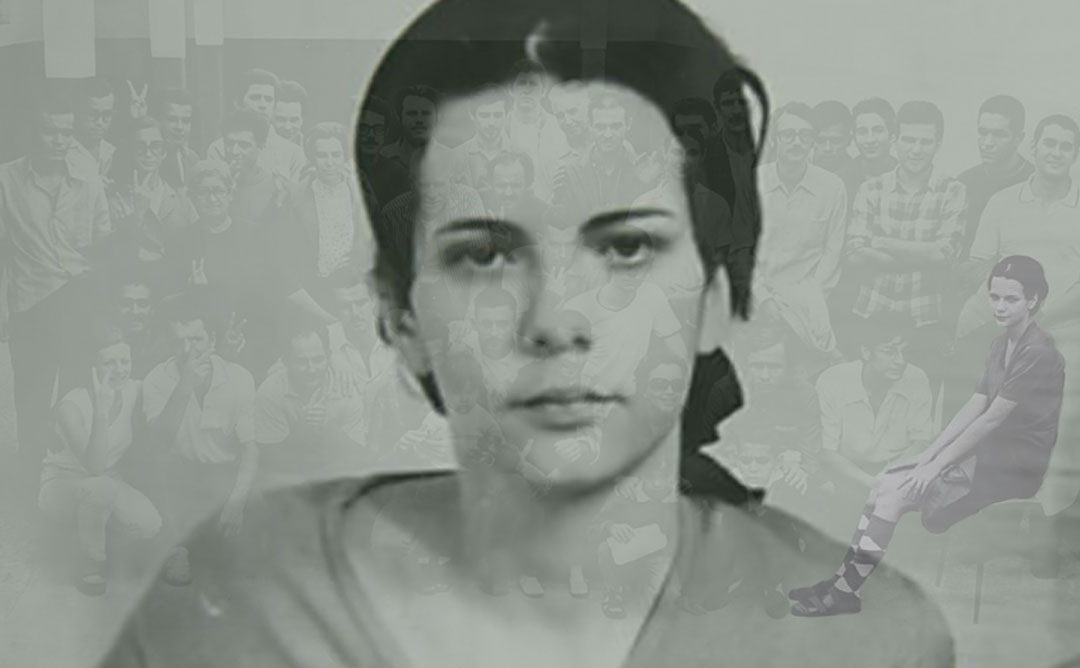

Vera Magalhães was one such student. Amidst the regime’s increasing repression and its efforts to silence critics (even moderate ones), in 1968 Magalhães, now 20 and enrolled in university, joined the clandestine Movimento Revolucionário 8 de Outubro (Revolutionary Movement of October 8), or MR-8, named after the day CIA-supported Bolivian troops captured Ché Guevara in 1967 [they executed him one day later]. Another group had been operating with the name MR-8, but the regime had captured almost all of its members, trumpeting the regime’s triumph to the public. In an attempt to discredit the regime, Magalhães and other members of the MR-8 began launching increasingly high-profile actions under the MR-8 moniker to indicate that opposition did not end with the arrest of a handful of individuals. Throughout 1968 and 1969, these armed groups mobilized in high-profile actions, even while the student movement faced increasing repression. They attacked banks, where they “expropriated” money from foreign capital and from the bourgeoisie, abandoning the student movement for armed struggle and bank robberies that helped fund the organization and marked an ideological attack on capital both foreign and domestic. In these expropriations, Magalhães, with her blonde wig and her two .45-caliber pistols, captured the attention of the media, which named her “Blonde ’90.”

In this context, Magalhães came to play a vital role in one of the boldest moves against the dictatorship. As the military used the new repressive Institutional Act Number 5 and Decree-Law 477 increase arrests and the use of torture against prisoners even while censoring the media, Magalhães and the MR-8 decided to act more boldly. She and a few of her colleagues came up with a plot to kidnap Charles Burke Elbrick, the US Ambassador to Brazil. No ambassador had ever been kidnapped before, and so the move was as innovative as it was daring. Magalhães spent time watching Elbrick’s route from his home to the US embassy in Botafogo, and even flirted with the chief of security in order to get him to reveal information about Elbrick’s routine. With the information she had gathered and the plans she had helped create, the MR-8 moved, and on September 4, 1969, they kidnapped Elbrick, the first time in world history that an ambassador had been kidnapped. MR-8 pledged Elbrick’s safe release in return for the release of 15 political prisoners and the reading on television of a declaration that expressed the MR-8’s visions and would break through the censorship the military had imposed; if the military refused to meet their conditions, they promised to kill the ambassador. The conditions put thus put Elbrick’s fate as much in the hands of the military as in the hands of his captors.

Although they did not realize it, Magalhães and her colleagues had perfectly, albeit accidentally, timed the kidnapping. At the end of August, president Costa e Silva had a massive stroke that had left the president incapacitated; not wanting to make clear that the country was presently effectively leaderless, the military had not announced his condition to the country. The regime thought it could safely pretend everything was fine until it found a way to replace the now-semi-paralyzed president. Unfortunately for military brass, the kidnapping of Elbrick had left them both unprepared and unable to quickly respond. Adding to the complications was the fact that the US, a major economic and political supporter of the dictatorship, was more than a little interested in seeing its ambassador safely released no matter the cost. In this context, the military split; some insisted that the government had to meet their demands so as to not lose the US’s support; others insisted meeting the demands would be a sign of military weakness, and that it was better to let Elbrick die.

Ultimately, those in favor of meeting the demands prevailed, but barely. The government read the MR-8’s statement, which proclaimed that Brazil was living in a military dictatorship and that the fight of the people would continue, on television. The regime also released fifteen political prisoners that the MR-8 had provided them; the list included student leaders like José Dirceu and Vladimir Palmeira; members of urban guerrilla groups like Maria Augusta Carneiro Ribeiro and Ricardo Vilas; journalist Flávio Tavares; labor activists Agonalto Pacheco and José Ibrahim; and older leftists Rolando Frati and Gregório Bezerra (who had been arrested immediately after the 1964 coup and who had also spent 10 years in prison for his communist activism during the government of Getúlio Vargas). It loaded them on an airplane and sent them to Mexico. Immediately after the plane, named “Hercules 56″ (the title of an excellent documentary on the kidnapping), took off, paratroopers arrived at Rio de Janeiro’s Galeão airport to try to stop them. Nonetheless, they were late, and the prisoners safely arrived in Mexico before heading to Cuba, where they met with Fidel Castro. After receiving training in Cuba, some clandestinely returned to Brazil, while others went into exile. [Of those who returned to Brazil, the military captured and killed two, gunning down both ex-sergeant Onofre Pinto and militant João Leonardo da Silva Rocha in 1974.] As for Elbrick, MR-8 stayed true to their word; with the release of the 15 political prisoners and the reading of the declaration, on September 8 Elbrick’s captors dropped him off at Maracanã stadium just as a soccer game was ending, and MR-8’s members disappearing into the crowd.

Magalhães and the others who had planned the kidnapping managed to disappear into the crowd in 1969, but they could not escape the regime’s security apparatus. In March 1970, the military arrested Magalhães while she was handing out political pamphlets; in the arrest, she was hit in the head by gunfire. Although wounded, the regime showed her little tolerance; angry at the MR-8’s ability to challenge the regime and in a period of intense repression, the security forces tortured the wounded Magalhães. She sustained three months of beatings, electrical shocks, and psychological torture; the physical abuse was so severe that she was unable to stand on her own without the support of somebody else.

In spite of the physical and psychological abuse, she never revealed names. Nor could her legacy be undone; that July, members of the Ação Libertadora Nacional (National Liberating Action; ALN) and Vanguarda Popular Revolucionária (Popular Revolutionary Vanguard; VPR) followed MR-8’s model, kidnapping German ambassador Ehrenfried von Holleben and demanded the release of more political prisoners. Ultimately, in July of 1970, the regime released forty more prisoners, including Magalhães; however, the physical effects of torture on her were clear. In a photo of the prisoners, she was seated in a chair, still unable to stand on her own.

After her release, Magalhães went into exile, first in Algeria and then in Chile, where many Brazilian exiles remained until the military coup of 1973 ushered in a right-wing dictatorship there as well. From there, she went to Europe with her husband (and comrade in MR-8), Fernando Gabeira (they eventually divorced). She ultimately settled in Paris, studying sociology at the Sorbonne under Brazilian professor Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who had also gone into self-imposed exile. When João Figueiredo issued a general amnesty in 1979, Magalhães joined thousands of other exiles in returning to Brazil.

Although she returned to Brazil safely, Vera Magalhães was never able to shake the long-term effects of the horrible abuses and torture she suffered at the hands of the military regime. She worked as an urban planner in the state government of Rio de Janeiro for years, but ultimately retired early at the age of 54, unable to work any longer due to her health. Throughout the rest of her life, she suffered from periodic psychotic episodes, kidney problems (from the beatings), and troubles with her legs, even while the medicine she had to take caused dental problems. Though hesitant to use her long-term suffering for financial gain, in 2002, she became the first woman to receive financial reparations from the state for her suffering at the hands of the military (previously, such reparations had usually only gone to families of those who had died at the hands of the military during the dictatorship). While the financial aid helped her with her medical problems, it could not cure her of them, and in December 2007, she died of a heart attack at the age of 59.

Although often overlooked in general narratives of student mobilization and opposition to the military regime, there is no doubt that Vera Magalhães played a key role in challenging the dictatorship. Although her politics and her fight for social justice led her to suffer severely at the hands of the military, she was proud of her ability to maintain her “human sense, ethical and political.”

Original version of this article can be found here.

[qpp]