When people think of Brasil and the environment the first thing that will spring to mind is the Amazon, specifically deforestation. What is lost in the noise is that Brasil and the Brazilian economy are amongst the greenest on the planet and that levels of deforestation have actually plummeted in the past ten years.

Brasil has the 3rd highest level of renewable energy production in the world, already standing at 85.4% as of 2009, and also one of the lowest carbon footprints per capita out of the major economies. Expansion of wind power in recent years, and announcement of 31 new Solar parks, will see further improvement in those figures, and balance the reliance on more traditional hydro-electric sources, such as Belo Monte. The potential environmental and social effects of large-scale hydro-electric projects are as elsewhere, a cause for concern – but ultimately, nations whose development was powered by fossil fuels and nuclear power are in a poor position to argue against the harnessing of these sources in the developing world.

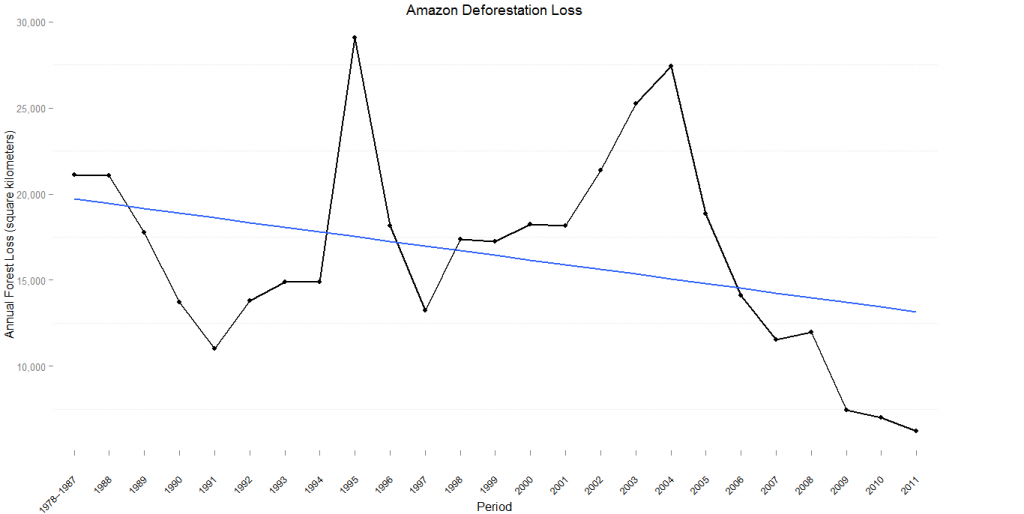

Source: World Bank

Received wisdom ignores the enormous strides and innovations Brasil has made in sustainability, in its move to an almost entirely renewable mix of energy sources, which, for a country its size, history & stage of development, is a radical achievement.

Without a doubt, in the past, Brasil’s governments had given little thought to the preservation of the Amazon. Since the times of Getúlio Vargas and the post-1964 dictatorship, the Amazon was targeted specifically for colonisation, often under paranoid fears for the country’s integrity. But this has changed dramatically over the past decade, and it is vital that Brasil amplify and maintain these advances on it’s own terms.

Misconceptions about Brasil and the environment are widespread, shaped by a peculiar set of post-colonial expectations that has even been called eco-imperialism, and international attitudes towards the Amazon, a region home to 20 million citizens, often cross the line of national sovereignty. In the eyes of foreign campaigners, little distinction is made between illegal logging in present day Brasil and the kind of planned deforestation and roadbuilding that characterised the environmental disregard of the Military Dictatorship era, such as the Trans-Amazonian Highway.

Also overlooked is that the most extensive deforestation in Brasil’s history occurred in the south of the country; the Mata Atlântica forest was once bigger than the Amazon, but 88% of its 1,500,000 km2 original estimated area has gone, originally through logging, creation of pasture and farmland. Most of this loss pre-dates even Brazilian independence, and much of the wood it produced was for the benefit of Europe, with the resulting farming for crops intended for European markets.

In fact, external pressures from Portugal and 19th Century Brasil’s true colonial ruler, the British Empire, meant that monocultural farming of coffee and sugar effectively signed the Mata Atlântica’s death certificate.

Brazilians are highly aware of their country’s historical exploitation by European powers and the United States and don’t take kindly to the selective finger-pointing that often comes from external actors today. This culminated in then President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s famous outburst at a 2009 summit, “I don’t want any gringo asking us to let an Amazon resident die of hunger under a tree. We want to preserve, but they will have to pay the price for this preservation because we never destroyed our forest like they mowed theirs down a century ago.” But aside from well intentioned concerns for the integrity of the world’s last great forest, Brasil has led the way, combining economic development with a low energy strategy that needs to be emulated, not criticised through the narrow lens of radically declining deforestation in the Amazon.

What is most interesting about this chart is that during the period of Brasil’s most rapid reduction in inequality and most stable economic growth in its history, deforestation has plummeted to record lows. This tells us that industrial and economic development in Brasil is actually benefiting the preservation of the forest. 20 million people live and work in the Amazon region, smart development, job creation and industrialisation in Amazonia has slowed the chainsaws. This has been combined with much more rigorous enforcement, although still under-resourced and under constant pressure from Brasil’s powerful Ruralist lobby. But even former slash and burn farmers have adopted high tech methods that have spiked production levels without increasing land use. All of this bodes well for the future of the Amazon, which is why it is in the whole world’s interest that Brasil and the residents of the Amazon continue to thrive.

Ironically, one area of the Amazon that upsets both orthodox economists and environmentalists is Brasil’s Zona Franca de Manaus and other massive industrialised Free Economic Zones in the heart of the jungle. Zona Franca de Manaus is Brasil’s electronic production hub, employing over 100 thousand workers and supporting families that no longer rely on the forest to sustain themselves. The payoff for the Amazon and Brasil has been enormous.

But this level of industrial development deep in the Amazon has upset foreign NGOs that have actively lobbied against further expansion despite this development being the most effective way to reduce pressure on the forest as a source of income for exploitation. The 20 million people living in the Amazon are not going to pack up and leave – the best hope for a sustainable future in the Amazon region is to expand economic opportunity for its residents in areas of work that do not involve cutting down trees.

From market fundamentalists on the other side of the equation, the Free Economic Zone creates an “artificial” advantage for Brasil – yet again ideological puritanism for unprotected markets trumps practical concerns for the environment and human welfare. At one stage the European Union was even in talks with the World Trade Organisation to question the legality of the Zones. At the same time European governments were offering economic donations for help to preserve the forest.

Challenges remain and vigilance is needed – the weakening of Código Florestal Brasileiro in 2012, led by ruralists in main coalition partner PMDB was a backwards step, and the possible ascent of their senator Katia Abreu to agriculture minister will be a massive blow for environmentalists.

But despite the ongoing battles, Brasil’s combination of economic growth, stunning increases in human development, low carbon emissions, renewable energy and plummeting deforestation would be heralded as a green success story – were it happening elsewhere.

Published November 2014.

Main image photo credit Kevin Jones. Amazon worker Andre Havro. Creative Commons.

[qpp]