When I first moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1991 tens of thousands of homeless families lived in cardboard boxes in Copacabana and locals would take a taxi to travel as little as one block to avoid being robbed by gangs of glue sniffing street children, many of whom would go on to be assassinated by the military police. There were an average of 3 armed car robberies per day and a kidnapping crisis was underway. I got in the middle of gunfire on my second day in town, in Copacabana at 2 in the afternoon. Another night, the city bus I was in lurched to a halt in the middle of the tunnel between Rio Sul and Princessa Isabel avenue as cars in front and behind us exchanged machine gun fire. Later, I was kidnapped by corrupt military police officers, pulled out of my taxi during a blitz, driven around the city for hours as, under the threat of getting a “blood test”, I negotiated the bribe for my release from $1000 down to $300. There was a violence crisis going on.

I lived in a favela in São Luis, Maranhão from 2000-2005. It had nothing to do with a hipster sense of “slumming it”, but was the result of rational choice. The favela was within walking distance of my job downtown and at the time Maranhão was tied with Santa Catarina as Brasil’s safest state. Everyone knew their neighbors and we would sit out on our front stoops every night drinking beer and shooting the breeze. While there were a few drug points in the neighborhood, they only sold marijuana and the local drug kingpin was someone known and respected in the community. I moved to São Paulo in late 2005 and, during a series of return visits, I watched São Luis go down the toilet. A drug gang from Pernambuco moved into the old neighborhood and started selling crack. Soon, it was no longer safe to walk down the street after sundown and neighbors stopped sitting on their front stoops at night. A police station was attacked with machine gun fire and gangs were burning city buses. The São Paulo trafficking faction, the PCC, was moving in. It got so dangerous that the city bus system stopped running at night. Today, Sao Luis is the second most violent city with a population over 1 million in Brasil. It is a place that is suffering from a violence crisis and its case is exemplary of the crisis that has been underway in Northern and Northeastern cities for the past decade. Fortaleza, one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country, is now the most violent big city in Brasil, with a homicide rate of 75/100,000. Other tourist destinations such as Natal, Macaio and Porto Seguro are currently suffering from murder rates that dwarf those in Rio de Janeiro. You wouldn’t know this from reading commercial news publications like the Guardian. 6 of the last 12 articles about Rio de Janeiro in the Guardian have been about violence, culminating with Dom Phillips recent piece that overplays the violence issue and downplays the significance of the military occupation – the first time the military has taken over a state government security apparatus since the dictatorship.

I lived in Rio de Janeiro for 8 years, first as a development professional managing social projects in places like Maré and City of God favelas and then as a local television producer specialized in filming in favelas. One highlight of this period was working as assistant producer of the three part BBC documentary Welcome to Rio, which involved 8 months of filming in places like Maré, Jardin Gramacho, Rio das Pedras, Lins, Rocinha, Juramento and Providencia. During this time I met and spoke with many people connected to the organized crime underworld. These combined experiences have given me enough knowledge to say a few things about violence in Rio de Janeiro.

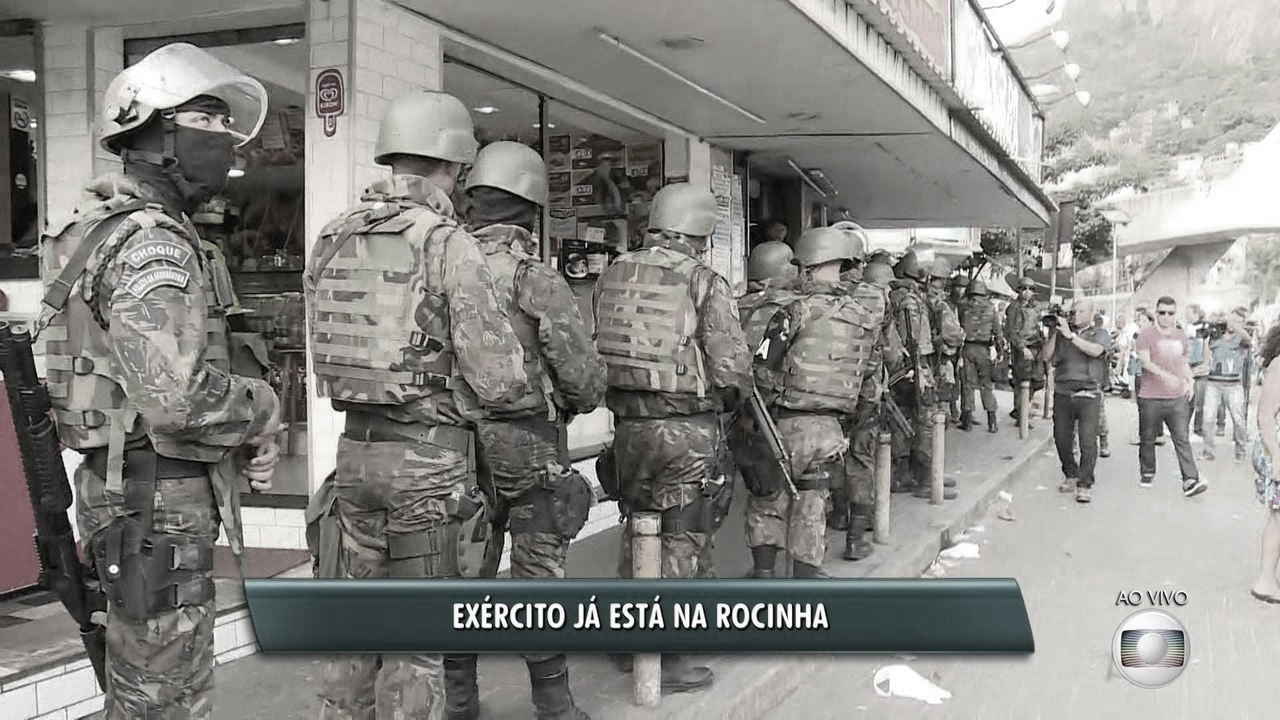

Despite media violence sensationalism written by journalists who don’t want to take the time or are not paid enough to fly up to the crisis areas in the North and Northeast, Rio de Janeiro does not rank in the top 100 most violent cities in Brasil. Although it’s homicide rate has recently creeped up towards 40/100,000, the state government regularly manipulates its crime statistics, as Alan Lima, Ben Anderson and I showed in the Vice/HBO documentary, The Pacification of Rio, in 2014. The Rio de Janeiro state government classifies violent deaths a few different ways. There is legitimate self defense, usually used to describe the hundreds of annual police killings, even those conducted execution style by shots to the back of the head at close range; there are homicides; and, importantly for the purpose of understanding the current artificially constructed violence crisis, there are the “violent deaths of undetermined cause”, a number which has fluctuated dramatically in recent years. In 2009, a year in which Rio de Janeiro had a homicide rate of 33/100,000, there were 3615 violent deaths of undetermined causes. By 2015, the most recent year that this statistic has been made available, the number dropped to 941. Whereas not all of these deaths are necessarily homicides, IPEA has stated that a significant number of them appear to be mistakenly categorized. Another area of flexibility in government statistic gathering is the case of disappearances. Thousands of them are registered every year in Rio and the number of police investigations fluctuates, in a scenario in which the police, drug gangs and militias are regularly discovered hiding bodies. To an outside observer the Rio de Janeiro state government appears to adjust the murder rate to suit its political purposes, lowering it, for example, in the lead up to the World Cup to calm tourists and increasing it to justify the recent military occupation. Unfortunately, reporters for international publications such as the Guardian never seem to scratch below the surface, frequently repeating whatever government numbers they see on the conservative Globo TV network without critical analysis, quoting Brasilian neoliberal editorialists like Miriam Leitão as if they were objective reporters. This in turn leads to articles like a recent one in which a Guardian journalist goes soft on the first military take over of a state security apparatus since the dictatorship.

Whereas violence remains a serious issue in Rio de Janeiro, nothing about the structure of the problem – large swathes of the city controlled by organized crime groups who have infiltrated and corrupted the police, military and local governments – has changed over the past 30 years. Rio is currently a lot safer than it was during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso presidency, when the state wide homicide rate surpassed 60/100,000. If Rio’s situation is business as usual, why has the Army taken over the state’s security apparatus now? There are a few theories under debate at the moment in Brasil, and I will summarize and analyze them here with the understanding that this is a complex issue with multiple causes.

1) To eradicate drug gangs

Anyone with any familiarity of the history of drug trafficking in Rio de Janeiro knows that this idea is ridiculous. Rio’s largest drug trafficking organization, the Comando Vermelho, was founded in 1979, and grew exponentially during the final 6 years of the Military Dictatorship. Not only was the Military unable to stop Rio’s largest drug gang when it ran the nation’s security, for the last 35 years it has been the primary supplier of their automatic weapons and hand grenades. This is an indisputable fact. All you have to do run a basic YouTube search to find home-made videos of Rio drug traffickers showing off their Brazilian military arsenal, like this amateur funk video, with 183,000 views, about the Amigos dos Amigos trafficking gang’s 50 caliber anti-aircraft machine gun in Mineira favela.

I worked on the production of an international television program in 2016, serving as interpreter for Ronaldo Carneiro, the former director of kidnapping operations of the Terceiro Comando gang, as he told the story of one of his biggest kidnappings. I watched as a frustrated director tried to get Ronaldo’s story to fit their pre-prepared script outline. He kept prodding him to say, “In the 1990s, Rio was a land of the haves and the have nots. I was a have not.” To the director’s frustration, Carneiro kept saying, “I was a have”. Contrary to what the production crew had hoped to depict, he wasn’t from a favela. He grew up in middle class family and went to private schools and his first contact with the Terceiro Comando was as a Captain in the Army Special Forces, selling them machine guns. This is hardly a unique story. When the local papers announced that the largest gun supplier to the drug trafficking gangs was arrested last year, nobody was surprised to discover that he was an army sergeant.

Although the current occupation represents the first time the Military has come in to take over security at the state-wide level it has periodically occupied different favelas in Rio for decades. There is not one case of this where the drug trafficking gangs were ever eliminated. I witnessed the relationship between the Brazilian army and Rio’s drug traffickers first hand in 2015. For over a year, 2750 military and national security forces occupied the Complexo da Maré, a group of favelas off the highway in from the international airport with a population over 100,000. I was there doing research and stopped to have a few beers at the end of the day in one of the many fantastic bars in Parque da União. As the sun went down, the troops left and the drug traffickers came out with their machine guns and set up their dealing tables on the streets. “This happens every night”, I was told.

If the Brazilian military was unable or unwilling to stop the Comando Vermelho while it was running the entire country, if it hasn’t been able to stop a 30 year constant flow of military weapons reaching the hands of the drug traffickers, and if it has never succeeded in removing a drug gang from a favela during all of its years of periodic favela occupations, why would anyone in their right minds assume that it’s been called in to stop the drug trafficking gangs?

2) To save the Temer government’s embarrassment at not being able to pass neoliberal retirement reforms

It is illegal to pass a constitutional amendment while any Brazilian state is under martial law. On Monday, in the midst of a nationwide General Strike against retirement reform, Congress announced that it will delay vote on the amendment until December. Blocking Temer’s proposed, unnecessary deep austerity cuts to the retirement system has been the primary objective of the 8 million members of the Central Unica de Trabalhadores labor union federation (Unified Workers’ Central/CUT) and its union and social movement allies in the Frente Brasil Popular coalition since last April. For the past year, they’ve been holding debates in neighborhood associations, churches and city councils across the country on what these reforms, which spare the retirement systems biggest abusers in the judiciary, military and government, would mean to the average worker. They’ve put pressure on local congressmen and, repeatedly over the past year, Temer has had to delay voting out of fear he didn’t have the 380 votes necessary to pass the amendment. Was it an accident that Temer ordered the military occupation 3 days before the General Strike? On February 16, CUT leadership issued a statement accusing Temer of staging the military occupation to hide his failure at passing pension reform and his recent corruption accusations.

3) The 2016 Coup is moving to stage 2, and Rio is a pilot project for a return to Military Rule

In February 2017, ousted President Dilma Rousseff warned of a second, more radical and more repressive phase of the Coup d’état which removed her from office – akin to the “Institutional Acts” in the years following the Military Coup of 1964.

When Michel Temer was instated as acting president, before the illegal impeachment proceedings against Dilma Rouseff went up to vote in Congress, he issued a decree reinstating the President’s Institutional Security Cabinet (Gabinete de Segurança Institucional da Presidência da República/GSI), which had been eradicated by Dilma Rousseff. The GSI has the task of providing support to the president on military and intelligence matters. Temer didn’t merely reinstate the agency, however, he gave it power over ABIN, the civil intelligence agency, and 36 other governmental agencies including the federal police and put 3rd generation Army General Sérgio Etchegoyen in charge. Etchegoyen is the architect of the Rio de Janeiro military occupation, which is already seizing property and committing human rights violations in Rio de Janeiro, most notably through blanket search warrants that cover all residents in designated poor neighborhoods, and stopping and frisking children as young as 6 at gunpoint. The occupation is scheduled to continue until December. The fact that the 1964 military dictatorship started with an army occupation of Rio de Janeiro is not lost on many Brazilians, who are worried that this represents the first stage in a return to military rule.

How could the government really solve the violence problem in cities like Rio de Janeiro?

The violence that plagues Brazilian cities is a direct result of the US government’s war on drugs policing strategy, which was adapted by the Brazilian government during the 1980s. The war on drugs is just as much of a failure in Brasil as it is in the United States, with an even higher death toll. Since it began, hundreds of thousands of people have been murdered in the cities of Rio and Sao Paulo alone, and, during the last decade, the problem has exacerbated in the North and Northeast, now home to Brasil’s most violent cities. Just as the mafia was weakened in the US when it ended prohibition, Mexican drug cartels are currently coming on hard financial times due to several US state’s legalization of marijuana. Neighboring Uruguay has also seen a significant drop in organized crime since it legalized Marijuana. Brasil partially decriminalized possession of small quantities of marijuana in 2006, but in poor neighborhoods, the police continue to treat recreational users as criminals. Why doesn’t Brasil simply decriminalize recreational drug use or at least respect the existing law regarding possession of marijuana? My theory is that the illegal drug industry is putting billions of dollars a year into the hands and campaigns of the traditional political clans. Was it an accident that a helicopter with 450 kilos of cocaine in it was apprehended on one of Aecio Neves’ top campaign financier’s ranch? Was it an accident that 20 kilos of cocaine was apprehended on Aloysio Nunes’ farm in 2009?

It may seem redundant to casual onlookers to see the Brazilian Military take over Rio’s security apparatus, because it has controlled its largest and most violent police force all along. The Brazilian military police are a holdover from the dictatorship and military police men are not legally accountable to the Brazilian rule of law, responding instead to military courts of their peers in a process where officers are rarely prosecuted. Most poor and working class people I’ve interacted with over the years feel that they are a large part of the violence problem in Brasil. Over the years Rio’s military police have been apprehended taking millions of dollars in bribes from drug traffickers, selling them guns, helping one drug faction fight against another, forming paramilitary militias that control entire neighborhoods on Rio’s west side, killing children, committing rapes, robbing ATM machines, cars and truck cargo, summarily executing thousands of primarily black youth, running death squads and infiltrating peaceful protest groups to incite violence. Since the fall of the dictatorship, criminologists have recommended that the Federal Government end the military police by merging it with the civil police and subordinating all police officers to the rule of law. During the Lula and Dilma governments, the PT party tried to do this 3 times, most recently through a bill introduced to the Senate by Lindbergh Farias. Each time legislation was introduced to the house or senate, the PT’s own conservative coalition partners killed the measure.

The purpose of this article is not to belittle the problems faced by the people of Rio de Janeiro or downplay the violence issue there. For the last 35 years city residents have suffered from living in a city not under full control of its own government, where huge swathes of territory have their own laws and draconian punishments and the police are as bad as the criminals. It should have been treated as an emergency when it started, back in the 1980s, but the paramilitary militias and drug trafficking gangs are now so ingrained in the power structure, that it is highly doubtful the current occupation will solve the problem. The military is already responsible for Rio’s security, through its military police force, which has caused tens of thousands of deaths while continually failing to stop violence in Rio over the past 35 years. What will change with more military on the streets?

Just as the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff was subsequently proven to be an illegal measure, initiated by a criminal who is now in jail and pushed through with the help of bribes, I have no doubt that the real motives behind Michel Temer’s move to turn Rio de Janeiro’s security apparatus over to the military will come to the surface soon. I sincerely hope that this doesn’t represent the first step towards a return to military rule. As journalists cheer-lead for the Brazilian military, keep in mind that there are serious human rights violations underway.

[qpp]