When former military dictatorship official Michel Temer became interim president, through what is increasingly appearing to be a fraudulent impeachment process, many people feared that there would be a clampdown on human rights activists. These fears were confirmed when he disbanded three ministries created by the PT government- Woman’s Rights, Human Rights and Racial Equality- and subordinated their former functions to the Justice Ministry. They were further exacerbated when he appointed former drug trafficking mafia defense lawyer Alexandre de Moraes as interim Justice Minister.

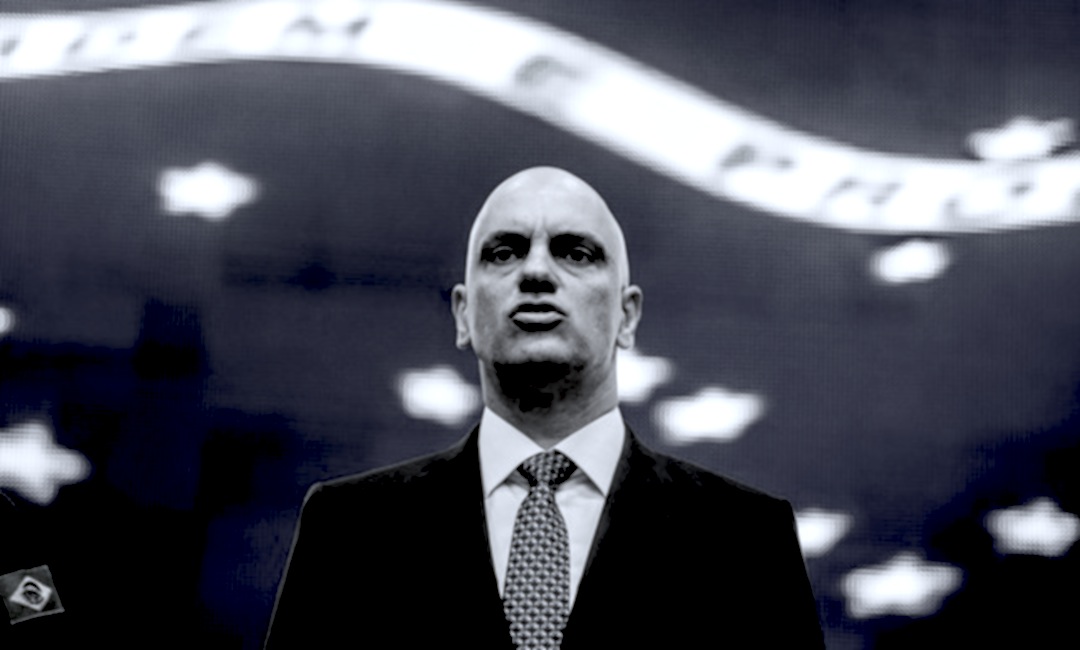

In this article, another in our partnership with Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil, law professor Marta Machado explains why Temer’s new choice of Justice Minister is cause for concern to anyone who cares about the right to free assembly.

The current political context suggests that protests will become fiercer. Alexandre de Moraes’ nomination as head of the Justice Ministry does not appear to be a coincidence. It seems to send a message that there is a lack of affinity between this government and democracy that goes beyond the questionable way that it took office.

When interim president Michel Temer was Justice Secretary for the Montero government in São Paulo in 1985 he created Brasil’s first Woman’s Police Station. At the time feminist movement had other demands that ranged from prevention systems, shelters, improved attendance and the end of legal use of the logic of legitimate defense of honor. The interpretation made by Secretary Temer was that we needed a specialized police station.

Thirty years later his response to the scandal over the group rape in Rio de Janeiro last month was the same: he announced the creation of a special department within the Federal Police. Without clarifying how the Federal Police would act in crimes against women, the vast majority of which fall under state jurisdiction, the interim president also ignored the total paradigm change that happened since the Maria da Penha Law passed in 2006 . Maria da Penha generated an integral policy for attending women that goes far beyond specialized police stations. Created in 2003 by the Lula government, the recently eradicated National Woman’s Ministry had a central role in approving the law and ran a series of campaigns to facilitate its implementation. If Dilma’s government can be criticized for not pushing through more radical gender policy advances such as abortion rights it is difficult to ignore all of its investment in domestic violence issues. Two relevant examples of policies championed by the executive branch were the National Pact for Confronting Violence Against Women and the campaign “Commitment and Attitude for the Maria da Penha Law- The Law of the Strongest”.

Temer’s response to this grave episode illustrates one of the marks of his style of government: transforming demands for rights and justice into punitive solutions. While setting up his interim team he removed the status of Ministry from the Women, Racial Equality and Human Rights departments and subordinated them under the Ministry of Justice. Then he nominated Alexandre de Moraes as Justice Minister. Nothing could symbolize this alchemical process better. Alexandre de Moraes facebook posts since becoming interim Justice Minister show that his central concerns are the actions of the penal agencies: fighting criminality, apprehending drugs, controlling the borders, security in the Olympics. His actions and public speech up to the moment also point to this theme. He passed Ordinance n. 611/2016, which suspends all of the Justice Ministry’s activities for 90 days with the exception of actions related to the national public security force and preparation for the Olympic Games. He announced that he intends to submit a bill to Congress to extinguish parole, altering the re-socializing role of the Penal Execution Law. “Just like in any civilized country in the World, if a person is sentenced to 15 years, he should do 15 years time,” he told the press. Even though the idea of “civilized” may be outdated, the tendency in most of the developed world is exactly the opposite. The European Council, for example, recommends the reduction of incarceration- to be considered a final resort- and increased use of alternative sentences.

Beyond the swelling of the prison system, there is something worrying about the nomination of Alexandre de Moraes for Justice Minister because there will be less space for exercising the right to protest.

Ex-Public Security Secretary for São Paulo state (under governor Geraldo Alckmin), Alexandre de Moraes became known for his defense of violent military police actions against protesters, especially [high school] students. He came to power in early 2015 and positioned himself against the recently approved state law (608/2013) that banned Military Police use of rubber bullets. In one of his last actions as São Paulo state security chief he was summoned by a judge to explain why the military police entered the Centro Paula Souza, occupied by students, without a search warrant. According to the judge on the case, “without a search warrant there is no possibility of complying with any decision. Without a search warrant any act is characterized as arbitrary violence to the democratic state, breaking with the fundamental guidelines of the Constitution.” Alexandre de Moraes, supported by state’s attorney Elival da Silva Ramos, defended himself with a very questionable legal argument. His defense is based on the legal concept of public goods- applied here for the first time ever- that allows private citizens to use force to defend their property during land conflicts.

The São Paulo military police’s actions, under his command, led to complaints and hearings in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, filed by the Committee of Mothers and Fathers in Mourning and sectors of the Public Defenders Office. One petition contains a long list of “truculent and disproportional” actions practiced by the military police. These actions include attacks on students with pepper spray, use of sound bombs and tear gas, aggression and immobilization of students and teachers, use of billy clubs against mothers, illegal arrests, use of lethal weapons during eviction attempts, verbal threats, psychological torture, confiscation of cellphones, students dragged down the pavement, injuries, students slapped by police, forceful removal of students from public streets, racism and illegitimate use of handcuffs on adolescents. The petition contains a section called “the public declarations of Alexandre de Moraes that violate the American Human Rights Treaty”, which questions the disposition of the ex-secretary to deligitimize the students actions and justify the use of force. In one of his clumsy notes to the press, the ex-secretary affirms that “the attitude of groups of protesters makes their political and criminal motives clear […], with diverse black blocks with covered faces, members of Apeoesp and people tied to political parties wearing communist youth t-shirts”. His tone of ideological persecution led to a Manifesto signed by more than 70 organizations including human rights groups, research institutes, academic centers and public defenders departments. The note criticized attempts to create an “internal enemy”, the use of police intimidation mechanisms against the constitutional rights of the students, the recurring use of illegal imprisonments and filing superfluous criminal charges “typical of dictatorial regimes”. It is worth noting that until then, the legal dispute over the criminalization of protesters was based on the obsolete National Security Law and attempted to accuse protestors of crimes of disobedience, defiance and damage to public patrimony. As of June 2016, the repressive apparatus now has a law that provides for a considerable hardening of punitive treatment to those who are considered enemies of internal order: the Anti-terrorism Law (13.260.2016). It is ironic that this law was proposed by two of Dilma Rousseff’s ministers and sanctioned by her shortly before she was removed from office.

Attempts to legally justify police violence show that there is a field of law under dispute involving the definition of the constitutional right to protest, the accepted ways to protest, the concept of public order and the limits to use of force in repression. This dispute is playing out on the streets and in the meetings between police and protesters but also in the institutions that can legitimize police actions. The State’s Attorney and the Judiciary are important moderating elements for abuses of authority (the São Paulo state institutions have not done much in this area). Positive feedback from the Public Security Secretary, which oversees the police command structure, enables all of the violent culture characteristic of this institution to run free. In this conflict, having a Justice Minister who openly supports this type of truculent police action is not a trivial matter.

The discourse of Alexandre de Moraes as ex-secretary and as interim Justice Minister is consistent in defending the actions of the military police and disqualifying protesters. Protests cannot obstruct traffic, “they have to leave one or two lanes free”, otherwise, “it’s vandalism and its a crime”. In the dispute over what is protest and what is crime, he says (in referring to the anti-impeachment protests): “I would not call them protests. They were acts that do not count as protests because they had no protest goal. They did, however, disturb the city. They functioned like guerrilla activities”.

Protests are unconventional acts by their very nature. They are disruptive and conflictual and permit people who are not in power to draw attention to their demands and be heard by public opinion, the media and the authorities. They are successful to the level in which they enable other groups enter the political arena and generate dialogue about their demands. In other words its the nature of any protest to break from normality, slow down the quotidian functioning of things. The declarations of the ex-secretary seem to negate the possibility of protesting at all.

At this stage, his statement about the right to protest, “no right is absolute”, seems like a euphemism for a zero tolerance policy. Or perhaps selective tolerance since the pro-impeachment protests, even though they blocked all the lanes of Paulista Avenue for two consecutive days, were not repressed by the police.

The current scenario implies a clampdown on protests. Not just protests questioning the legitimacy of the interim president but also those made by people whose rights are affected by the announced cuts in social programs and austerity measures. The visible lack of dialogue with the social movements also suggest that there will be days of confrontation ahead. In the field of police action, the closing of institutional channels for accommodating interests and demands will lead to the radicalization of forms of protest. In this context, nominating Alexandre de Moraes as Justice Minister does not appear to be a coincidence. It appears to announce that there is a lack of affinity between this government and democracy that goes beyond the questionable way that it took office.

[qpp]