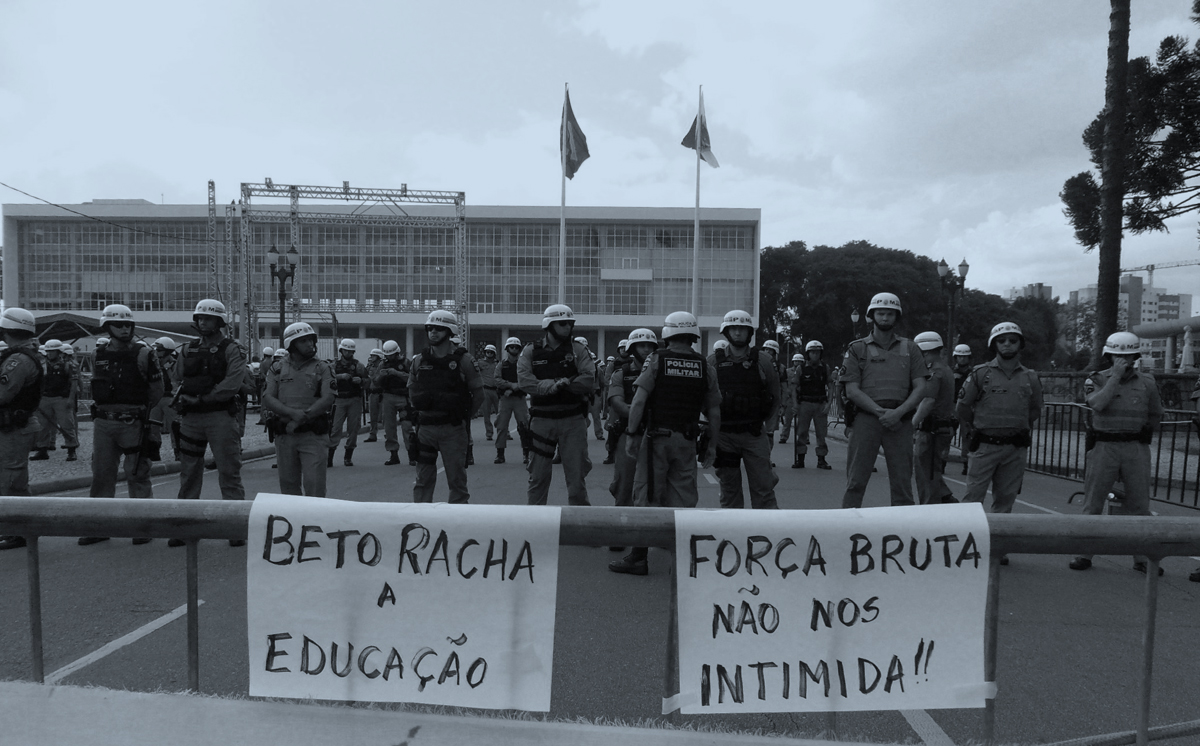

On April 29 2015, the Military Police of Paraná attacked thousands of striking teachers in Curitiba with tear gas, pepper spray, dogs, and rubber bullets. Hundreds were wounded, and the governor has attempted to divert responsibility by blaming shadowy infiltrated anarchist “agitators.” This is the story behind the carnage, from a Paraná university professor who witnessed it.

Shocking images of the violent military police repression of striking teachers, students, and civil service employees that wounded 200 in the state of Paraná on April 29 have been seen around the world. Contrary to the narrative of governor Beto Richa, uncritically repeated by the right-wing mainstream Brazilian press, the carnage was not the result of a “confrontation” between innocent police and infiltrated anarchists or irrational, selfish teachers. Rather, the violent repression, out of all proportion to any actions the teachers took, was the culmination of nearly three months of brazen intimidation and attempts to erode hard-won labor rights.

The 2014 Election: Beto Richa’s Bag of Tricks

Carlos Alberto Richa (known as Beto Richa) has been the governor of Paraná since 2011. Son of a former governor and member of an old political family, Richa is a member of the Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB), the party that carried out sweeping neoliberal reforms during the 1995-2002 presidency of Fernando Henrique Cardoso and has since drifted progressively further to the right. In recent months, some members of the party, including its 2014 presidential candidate, senator Aécio Neves, have gone so far as to align themselves with far-right demonstrators calling for a military coup to overthrow the center-left government of President Dilma Rousseff and the Workers’ Party (PT).

Last year Richa ran for re-election at the head of a 17-party coalition. He announced that the state’s finances had been put in order, promised to “improve the quality of education,” and guaranteed that “the best is yet to come.” “There’s going to be money in the bank,” he boasted, “because we cleaned up the state’s finances.” He won with 55% of the vote. But just a few weeks later, Richa announced that the state was in dire financial straits that demanded sales tax increases on 95,000 products and required a 40% increase in vehicle licensing fees. No sooner had his second term begun than Richa laid off 29,000 temporary professors without severance pay and partially suspended vacation pay for state employees. In early February, he sent the state legislature a series of bills that came to be known as the “Package of Evils,” proposing the rollback of longstanding rights for state employees and raiding their pension fund.

February: The Battle over the “Package of Evils”

The “Package of Evils” became public on February 4. It consisted of 13 measures, including a reduction in the number of teachers and cuts to science and technology funding. It also proposed reductions in the transportation assistance provided teachers and ended automatic seniority raises. The government labeled its proposal an “urgent measure” and attempted to push it through the legislature without debate. Three days later, more than 10,000 primary and secondary school teachers and employees met in a football stadium and voted to strike. They were followed shortly thereafter by the faculty and staff of the seven state universities.

The lynchpin of the “Package of Evils” was pension reform, through which the state government hoped to appropriate 8 billion reais (about US $2.75 billion) from the state pension fund, paid for by employee contributions. In addition, Richa proposed a 4,600-real (about US $1,600) per-month cap on individual pension payments.

February 10 more than 20,000 state employees protested in front of Paraná’s unicameral state legislature, and late that afternoon they occupied the chamber and blocked a vote on the package. Three days later, with the chamber still occupied and thousands of demonstrators outside, government-allied deputies, who enjoy a large majority, entered the legislature in an armored transport vehicle owned by the riot police, hoping to vote on the proposal in the building’s restaurant. The use of an armored vehicle to avoid striking teachers generated so much public ridicule that the deputies were forced to table the bill. At this point, polls showed 90% support in the state for the teachers’ strike, and 80% support for the occupation of the legislature.

After nearly a month on strike, the teachers and state government reached a deal. In exchange for a return to work, among other concessions, the state government promised that it would not attempt to use pension funds for other purposes.

March and April: New Pension Reforms, New Strikes

However, shortly thereafter the Richa administration introduced a new pension reform that held to the letter of the agreement but blatantly violated its spirit. Instead of appropriating 8 billion reais from the pension fund, the government proposed adding to it 33,000 teachers who retired prior to its creation. The current pension fund relies upon employee contributions; previously, employee pensions were paid directly from state coffers. By transferring retired employees’ pensions to a fund into which they never paid, the state government would add 143 million reais per month in costs to the fund, or a total of nearly 7 billion reais over the remainder of the Richa administration. Though the method would be different, the result would be the same – the bankrupting of the teachers’ pension fund. In response, on April 22, the primary and secondary teachers and staff and university professors voted to strike again, this time joined by pension fund employees and health care workers.

The Last Week of April: The Stage Set for a Showdown

On April 15, the state legislature opted to fast track the pension reform and determined that the final vote would take place between April 27 and 29. On Saturday, April 25, the state government launched the largest police operation in Paraná’s history, placing 4,500 military police around the state legislature in an attempt to block another occupation of the building and intimidate demonstrators. (Military police in each of Brazil’s states are directly controlled by the governors.) The operation involved not only riot police, the special forces battalion, and trained dogs, but also military police brought from all over the state, including the “Border Battalion,” normally stationed 700 km away on the Argentine and Paraguayan borders. The intent to intimidate was clear, since the police were in place well before demonstrations were slated to begin. In addition, the police set up innumerable barriers around the legislative building and prohibited demonstrators from camping out nearby.

Monday, April 27, about 5,000 teachers, professors, and staff gathered in front of the legislature. The moment of greatest tension occurred when the police prohibited the demonstrators from bringing a large truck equipped with loudspeakers into the area, although they did eventually allow two smaller trucks to enter. They also set up more barricades in the area. That day the first of two required votes was taken on the pension reform; it passed 31-21.

Early Tuesday morning, a violent police operation forced the removal of the sound trucks and moved the barricades further out, reducing even more the space available to demonstrators. Eight protesters were wounded in the melee. As the day wore on, the number of protesters grew to about 8,000, as pension employees and health care workers joined the demonstration. Around 11:00 a.m., when the demonstrators attempted to move their sound trucks back into the protest area, they were violently attacked by the police, who launched canisters of tear gas and pepper gas, fired water cannons, and shot rubber bullets into the crowd. The largest sound truck was forced to move still further away from the protest area, and its key was seized by the police.

April 29: Chronicle of a Massacre Foretold

All these tensions came to a head on April 29, the day the final vote on the pension reform was to be taken. 20,000 protesters filled the area outside the legislature, and their anger grew as the vote neared. That morning, the speaker of the legislature had forbidden the presence of spectators in the gallery; the session would take place behind closed doors. A helicopter buzzed the crowd and blew tents away while the police readied themselves to go on the attack. Around 2:50 p.m., when protesters pushed against one of the barricades police had set up to keep them away from the legislature, the police launched a shockingly repressive operation that lasted over two hours with uninterrupted firing of tear gas, pepper gas, water cannons, and flash bombs and the use of dogs. Within a few minutes the protesters had retreated 50 meters. Between the demonstrators and the police innumerable wounded lay on the pavement. Snipers posted on the roofs of surrounding buildings launched tear gas toward the plaza below, as rubber bullets wounded more protesters and prevented the rescue of the wounded. A state legislator was attacked by a German shepherd, while a cameraman fell victim to a pit bull. The intensity of the assault only began to diminish after 5:00 p.m. Meanwhile, inside the legislature the majority, allied with the governor, refused to interrupt the vote. “Well, no one is firing anything here inside, so lets vote,” speaker Ademar Traiano said. Once again, the bill was approved with 31 votes in favor.

The press the next day called it a “confrontation.” Nothing could be further from the truth. What happened on April 29 was a meticulously planned massacre that involved an extraordinary contingent of police and an enormous quantity riot-control weapons. The government claimed that 20 police officers were injured, but not one of these claims has been proven, and social networks have been filled with mocking images of policemen covered in pink or red paint to imitate blood. On the part of the demonstrators, over 200 were injured, some seriously, mostly due to being hit with rubber bullets at close range. The enormous national and international repercussion of the massacre, widespread disbelief at Richa’s desperate attempts to blame anarchist “black blocs” for the confrontation, the renewed commitment to the strike, and the solidarity of hundreds of movements and organizations from around the country with the protesters leaves some room for hope that this crime will not go unpunished.

In the midst of this brutal attack, there is still more cause for hope. The vitality and resilience of the educators’ movement shows that the imposition of neoliberal “reforms” can no longer happen simply through manipulation and the production of false consensus. It is no longer possible to neutralize growing popular resistance except through repression on a massive scale. And even as it gives us hope, it is also cause for concern over the future of our democracy.

(Translated by Bryan Pitts)

(Photographs: Gilberto Calil)

[qpp]