There are many forces outside of Brazil – those that have moved to the right – who want to crush this peoples’ response to democracy and justice and economic justice. We have to fight against that in any way that we can.

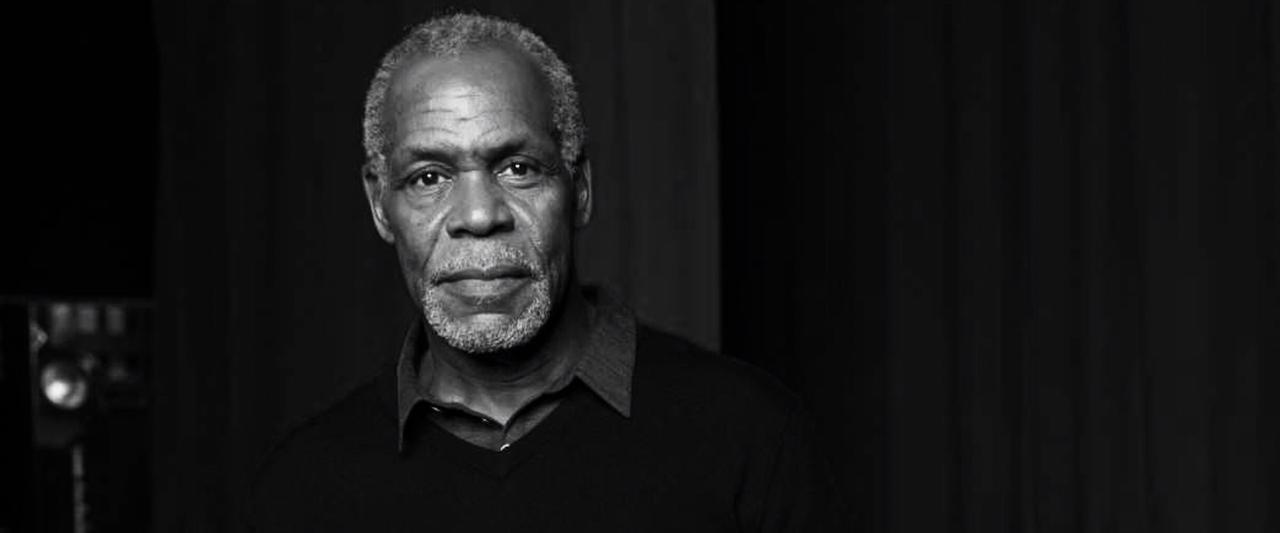

Danny Glover is an American actor, producer and activist who has a long history of solidarity with 3rd World liberation struggles. He is an active board member of both the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), and the TransAfrica Forum. His independent film production company, Louverture, partners with progressive filmmakers and producers around the world and particularly from the global South. It’s latest film, Hale County This Morning, This Evening is currently in theaters in the US, having recently won the Sundance Film Festival award for best documentary.

Glover is also a friend of political prisoner Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and recently visited him in the Curitiba Federal Police Headquarters where he has been denied his legal right to run for President, in violation of both the UN Charter on Civil and Political Rights, and Brazilian law 311/2009 which requires the government to respect UN Human Rights Committee rulings.

I interviewed Mr. Glover in September, 2018, for a web TV program for the progressive Brazilian news medium Brasil 247. The following are the transcripts from the interview, edited for readability.

-Brian Mier

It’s a pleasure to have you here and I think it’s a good opportunity too, because everybody knows you from the Lethal Weapon movies and they still show them on TV a lot down here, especially in the afternoon sessions. And everyone knows you from Predator 2, but not so many people know about your political activism and some of the other things you are involved in. So I’d like to start off by asking you when did you first become a political activist, how did it happen and what was going on at that time?

It was as a student really. Early in my life, and particularly in college. The college I went to was a very progressive, at least the student body was very progressive, and we were able to carry out several actions in regards to [creating] a school of ethnic studies, a strike and also in support of community organizations and many other things, changing the nature of education in the college and using the college as a platform to engage with the community as well.

What were the biggest issues going on at that time and what’s changed since then?

It’s interesting. One of the key issues was access, you know. The issue of access for people of color whether of Hispanic descent, of Asian descent, of African descent, was an issue for us and I am sure that in Brazil there is the issue of access for those people who have been previously disenfranchised and those who were left out of the equation in terms of their aspirations and their political needs as well.

You also founded an interesting independent production company called Louverture, which was named after Haitian Revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture. I know that you’re company has produced a lot of very interesting political films, films that deal with subjects like human rights, sovereignty of 3rd world peoples, and the struggle against colonialism. How does your activism influence your film production work and vice-versa?

Well, when I decided to become an actor, I was able to find a writer, a great writer, Athol Fugard, a great South African writer. And so I did his work, his plays, which I acted in, as far back as 1975. The fact that I did those plays and their political nature placed me right in the center of the conversation and the movement around African liberation support which was support of former colonies such as Zimbabwe, Namibia, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau and Angola as well as South Africa. So right there the political nature of the work placed me in that discussion and consequently it served as my first success which led me to join films. [In 1987] I played Mandela in a film that was funded by and produced by HBO and channel 4 in the UK. People saw the film and in fact when I met Mr. Mandela later on in 1990, he told me that they smuggled the film into the jail for him to see it. When I did that film I had already finished Places in the Heart, Witness, Silverado, The Color Purple and the first Lethal Weapon. So the nature of my success came first through he work that I did in terms of the brilliant work, the wonderful writing from the great play-write, Athol Fugard.

Speaking of your activism and your independent films, you developed a friendship over the years with Hugo Chavez, the former president of Venezuela. And at one point, Mr. Chavez was talking about funding a film for you about the Haitian revolution. What is the biggest lesson that you learned through your friendship with Hugo Chavez?

First of all he was probably one of the most accessible leaders that I had been around. And I believe that his extraordinary gift in mobilizing people and certainly in getting people excited about the possibilities of change was extraordinary. He epitomized that. He would be able to identify something that needed to be done and took action on that – took real action. In some sense, to change the narrative. I think that was his greatest gift. The people believed him when he said he was going to do something, he was going to bring something about, he actually did that. Often you don’t find leaders who are able to do that, who are able to translate what they think or say that needs to be done into real action. Certainly that was one of the things that I though was very instrumental and very strong about him. There are certain other things that you can say that, when you have someone who is, as, how would you say, as charismatic, someone who is all encompassing in so many ways, it seems that there is a chance that the real organizing that needs to be done doesn’t get done and that may have been one of the difficulties that he faced as well because at the same time someone who takes on the responsibility of everything often is not able to set up the kind of structures or build the kind of capacity needed to carry out what he wants, if you know what I mean. So at the one time, I’m telling you about one of his extraordinary gifts in terms of leadership, but also it may be a handicap in terms of building capacity and organization, in my opinion.

Let me get something straight, because this is going to be broadcast. We were not able to accomplish the objective [to make the film], and understand this: Latin America knows more about the Haitian revolution – Latin America and the Caribbean – than people in my country. And that is tragic because there were three revolutions that happened within a 15 year period, the American revolution of 1776, the French revolution of 1789 and the Haitian revolution of 1791. And the Haitian Revolution was the only revolution that actualized the ideals of the two previous revolutions that all men were created equal. And it was the most dangerous affront to the new system that was evolving, that was in this early stage of development, and that is capitalism, because the first capital for the capitalist system and the first engine of the industrial revolution was through slavery. Cotton was the most important issue in the development of the United States in the early part of the 19th Century. We don’t know that and we don’t understand the role that the Haitian revolution played in the nature of all the things that happened in Latin America. It was Simon Bolivar who came to Alexandré Petion, the President of Haiti, in 1813 and received provisions, arms, guns, men in order to liberate South America.

What you are saying about Haiti is really important and I think a lot of Brazilians probably also don’t know that Bolivar was armed by the Haitian President before embarking on revolution in South America, but I would like to change the subject a little bit now and ask you about your friendship with Lula. I know you visited him in jail in Curitiba. How long have you known Lula for and how did you meet him? And what do you think about his situation right now?

Lula is my friend. President Lula is my friend. I met Lula, first through reading about him, and the work that he did in terms of organizing CUT and I learned about him in his previous presidential campaigns but I met him the first time in 2004 in Brasilia. As he was president at that time, I met him – I think it was 2004 or 2005 I’m not sure. But I met him and I met him on other occasions, and I think he is one of the most extraordinary men or legislators or politicians, however you want to describe him, in Latin America and perhaps one of the most important in the world as well. The work, and his extraordinary journey from being a worker without a formal education to the leadership and founding of a union and also to the presidency of the country is, I think, one of the most amazing things to happen not just in the early part of the 21st Century but of all times, and certainly in the 20th Century. His convictions, his ideals, his extraordinary passion and love for people and for those who are the most vulnerable is extraordinary. And certainly I think that the situation here, as noted by the United Nations and the Rapporteur regarding human rights, is unjust and it is a disgrace. I got a chance to spend some time with him as well as with Dilma and we talked, he was very optimistic at the time when I saw him on June 1st , it is nearly October 1st and that was 4 months ago. And he is still incarcerated unfairly and unjustly. But certainly the situation has not allowed him to rightfully run for President. It is a travesty to the whole system of Democracy and certainly is a tragedy for the Brazilian people as well.

We know that the Workers Party has nominated Fernando Haddad in Lula’s place and we have to work on behalf of giving him the election. We have to mobilize at this particular moment and this is an opportunity to have our voice heard within the process. There are many forces outside of Brazil and certainly in Latin America – those that have moved to the right – who want to crush this peoples’ response to democracy and justice and economic justice. We have to fight against that in any way that we can. It is our responsibility, with the Brazilian people and with their support from people around the World but it is their vote that counts. Election day, on October 7th , is a very important day for me, because this is my mother’s birthday, and my mother was a woman of justice and fairness and democracy. I am sure that if she was with us today she would want the Brazilian people to have their justice, their right to make decisions that effect and that uplift all Brazilians and particularly those of the marginalized, African descendants, indigenous, first nations people, Quilombo people and women.

Watch the complete interview here

[qpp]